That was one of those moments that conscientious parents dread, because I couldn't definitively answer her question. The reality is that historical precedent dictates that even life-changing events will be remembered differently as time passes.

Consider: in 1862 a total of 78 civilians, most of them women and girls engaged in munitions work, were killed in an explosion at the Allegheny Arsenal in the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh.

|

| Pittsburgh Daily Post, 18 September 1862 |

You'd be forgiven if this was news to you; for decades, such history was neglected in local school curricula. And it also was understandable that the event was overshadowed even at the time by news of the Battle of Antietam. Fought near Sharpsburg, Maryland that same day, more than 23,000 men were killed, wounded, or went missing. No article about Antietam fails to mention that 17 September 1862 was the bloodiest single day in American military history. The loss of 78 civilians some 180 miles north in Pittsburgh paled in comparison, and the Battle of Antietam even pushed the Arsenal story to page 3 in one local newspaper.

Still, the Arsenal deaths represented the worst loss of civilian life during the entire Civil War. Those victims deserve present-day honor as well.

The Allegheny Arsenal was initially designed as a supply depot during the War of 1812 for the US military during its ill-conceived attempt to invade the region we now call Canada. The military presence at the Forks of Ohio (as Pittsburgh was initially known) had progressed since the colonial era from Fort Pitt at the Point, to Fort Lafayette along the Allegheny River. The latter had been deemed inadequate and closed in 1814. Renowned architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe was commissioned to design the main building at the new Pittsburgh Arsenal. His proposed structure was greatly altered to this final form:

|

| Allegheny Arsenal, circa 1870-1909, gelatin silver print. University of Pittsburgh Historic Photographs |

The Arsenal typically employed between 100-200 people a day in various outbuildings, but production of what were termed 'military accoutrements' ramped up once the Civil War began. Nearly 1,100 employees passed by these imposing Arsenal gates each day on their way to work.

|

| Gateway to Arsenal, circa June 1937. Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh |

As so often happens in wartime, many women had come to do what would in times of peace be considered men's work. Of course, in times of peace, there would not be quite the same insatiable demand for Minié balls and powder-filled cartridges.

| Powder cartridges, Heinz History Center Collection |

| Modern representation of powder cartridge, Heinz History Center display |

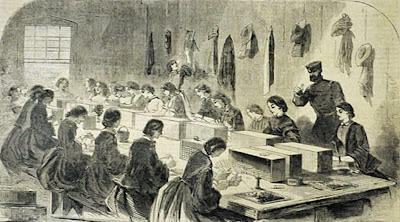

On 17 September 1862 there were 156 women and girls, plus some men and boys, at work in the laboratory out-buildings of the Arsenal. They were rolling .54 and .71 caliber cartridges and filling cannon shells with highly combustible black powder.

|

| Winslow Homer engraving of women and girls rolling cartridges at a federal arsenal in Massachusetts. Harper's Weekly, July 1861. |

An average day of such work would yield 800 rolled cartridges per person, for wages starting at 50¢ a day for the youngest and inexperienced. Contrast this with the 43¢ a day that Union privates received, with payment delayed for months at a time while their desperate families waited for such income. It's easy to understand why these jobs were attractive to the poor, mostly Irish immigrant girls and women of Pittsburgh. Many of Pittsburgh's poorest and most vulnerable families were left grieving the loss of their wives and daughters -- and the wages they'd earned -- when the Arsenal went up in flames.

Contemporary newspaper accounts spared no details about what horrors greeted Pittsburghers rushing to the scene. Skip the following description from the Daily Post if you are sensitive to graphic descriptions:

Of the main building nothing remained but a heap of smoking debris. The ground about was strewn with fragments of charred wood,

torn clothing, balls, caps, grape shot, exploded shells, hoes, fragments of dinner baskets belonging to the inmates, steel springs from the girls’ hoop skirts, cartridge paper, sheet iron, and melted lead. Two hundred feet from the laboratory was picked up the body of one young girl, terrible mangled; another

body was seen to fly in the air and separate into two parts; an arm was thrown over the wall; a foot was picked up near the gate; a piece of skull was found a hundred yards away, and pieces of intestines were scattered about the grounds. Some fled out of the ruins covered with flame, or blackened and lacerated with effects of the explosion, and either fell and expired or lingered in agony until removed. Several were conveyed to houses in the borough and to their homes in the city. Of these, four or five subsequently died.

Some victims simply vanished without a trace in the blaze. Less than half of the bodies were identifiable. The unidentifiable remains were buried in a mass grave at Allegheny Cemetery, and 15 Catholic girls were laid to rest in the adjacent St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church Cemetery.

The cause of the Arsenal explosion has never been fully determined. A coroner's inquest began immediately that evening. Long deliberations eventually determined that a spark from the combustion of either an iron horseshoe or iron-rimmed wagon wheel was ignited when the metal contacted black powder dust, which had been routinely swept onto the macadamized road in front of the Arsenal. Those roads happened to contain a material called churt, which in certain combinations contained flint. The spark that was ignited spread to the many 100 pound barrels of black powder stacked all around the Arsenal premises, and an inferno ensued.

This remains the accepted version of events, but the reasons behind the explosion and the sequence of events have always captivated and mystified. Many questions remained after that original 1862 civil inquest, which cited negligence on the part of Arsenal administrators for not stringently enforcing safety regulations. A military board of inquiry was held a month later, which exonerated the Army officials and instead blamed the wagon driver and another (deceased) employee for negligence.

In 2012 a great deal of local press coverage marked the 150 anniversary of the Arsenal explosion (see the end of this entry for partial list of coverage), and a short video was produced by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. My daughter and I attended a lecture at the Heinz History Center presented by Jim Wudarczyk and Tom Powers of the Lawrenceville Historical Society. We returned to the History Center a week later to attend a mock cold case inquiry presided over by former Allegheny County Coroner Cyril Wecht to determine the explosion's probable cause.

At the modern mock inquiry, expert witnesses were called to reconstruct history. We learned about munitions, the roles and lives of Civil War era women, the history of the Arsenal, and various military issues. All the while, a young lady with nimble fingers dressed in period costume sat to the side and rolled cartridges, just as Arsenal girls and women would have done 150 years ago.

|

| Kate Lukascewicz portrays an Arsenal employee. Heinz History Center, September 2012 |

The jury in this mock trial found that the Army officials in charge were negligent in assuring the safety of the facility, much as the original coroner's inquest had done.

While the case testimonies were fascinating, what moved us was a brief commemoration in honor of those who had died. Members of the audience had been given index cards with a victim's name. Each stood and read their name aloud. My daughter was given Susan McKenna's name. We knew nothing about Miss McKenna, although we later learned that she was 18 at the time of death and that her remains were identified by a set of teeth. She was buried at St. Mary's Cemetery.

For a few moments my vibrant and beautiful 13 year old stood in silence to honor this 150 year old ghost whose life had been abruptly cut so short.

And in those moments, I think we found the answer to the questions she'd pondered about the nature of commemorations. So long as caring people honor the past and seek to learn from it, those who suffered and died will always be remembered.

The nature of the commemorations may change, but respect can always be paid. This was brought home to us when Marie Gray, a descendant of Arsenal blast victim May Collins, noted how sad it was that these victims had not received acknowledgement as heroes and patriots, and attested to how meaningful she found the History Center's belated tribute to be.

It is never too late to remember.

My daughter and I later drove to Allegheny Cemetery in Lawrenceville to visit the burial site of the explosion victims. We found Susan McKenna's name engraved on the memorial along, with other names we'd come to recognize.

This is actually the second memorial on the burial site, the original obelisk with its listing of 40 or so names having deteriorated and been replaced.

|

| Original Allegheny Arsenal memorial. From The Allegheny Cemetery Its Origin and Early History |

An engraving on the current memorial reads:

Time and its destructive elements obliterated the inscription and names on the original monument erected on this plot in 1863, which was in memory of the victims who lie buried here. The present monument was erected to keep ever sacred the memory of all seventy eight who lost their lives in this explosion.

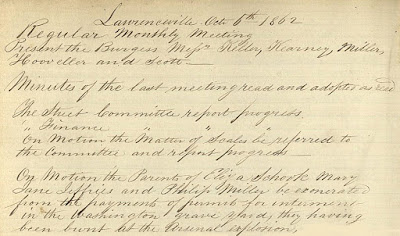

This memorial was dedicated in 1928, having been raised by the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War and that organization's Lady's Auxiliary. All 78 victims are listed on the memorial, although only 39 coffins are buried beneath. Some fifteen people were buried on the other side of the fence in St. Mary's Cemetery. Three victims were buried at the circa-1812 Washington Burial Ground (where today's Main and Fisk Streets, Government Way and the Carnegie Library exist today). The borough voted to relieve their grieving families of the burden of burial expenses two weeks later.

| |

| Lawrenceville Borough monthly meeting minutes, October 1862 Courtesy of Pittsburgh City Archives |

The victims buried there would have been reinterred at Allegheny Cemetery in the late 1880s when the Washington burial ground was repurposed.

According to a May 1928 Pittsburgh Press article, a full list of victims was compiled through research and outreach to surviving relatives. It is as complete as such research could make it, although variations in given names and recorded names exist.

I am far less interested in the causes of the explosion than I am in the lives of the victims -- lives that were so cruelly cut short. The best way, I think, to honor those who were lost that day is to pause for a moment, as we did that weekend, to read their names.

The inscription on the current memorial was copied from the original, and is followed by the list of names:

_______________________________________

Tread softly this is consecrated dust, forty-five pure patriotic victims lie here. A sacrifice to freedom and civil liberty, a horrid moment of a most wicked rebellion. Patriots! These are patriots graves, friends of humble, honest toil, these were your peers. Fervent affection kindled these hearts, honest industry employed these hands, widows and orphans tears have watered this ground. Female beauty and manhood's vigor commingle here. Identified by man known by Him who is the resurrection and the life, to be made known and loved again, when the morning cometh.

Elizabeth Ager

Mary Algeo

Mary Amarine

Hannah Baxter

Barbara Bishop

Joseph E. Bollman (father)

Mary A. Bollman (daughter)

Rose Brady

Ellen Brown

Alice Burke

Sarah Burke

Catherine Burkhart

Bridget Clare

Emma Clowes

Mary Collins

Melinda Colston

Mary Cranan

Agnes M. Davison

Mary A. Davison

Mary A. Donnelly

Ann Dillon

Kate Dillon

Kate Donahue

Sarah Donnell

Mary Donnelly

Magdalene Douglas

Mary A. Dripps

Catherine Dugan

Nancy Fleming

Catherine Foley

Susan Fritchley

Sarah George

David Gilliland

Virginia Hammill

Sidney Hanlon

Hester Heslip

Mary J. Jeffrey

Mrs. Mary J. Johnson

Annie Jones

Catherine Kaler

Margaret Kelly

Uriah Laughlin

Eliza Lindsay

Hannah Lindsay

Adaline Mahrer

Ellen Manchester

Elizabeth Markle

Elizabeth J. Maxwell

Sarah A. Maxwell

Ella McAfee

Kate McBride

Maria McCarthy

Susan McCreight

Ellen McKenna

Susan McKenna

Grace McMillan

Andrew McWhirter

Mary Ann McWhirter

Catherine Miller

Philip Miller

Mary Murphy

Melinda Neckerman

Alice Nugent

Margaret O'Rourke

Mary Riordon

Martha Robinson

Mary Robinson

Mary S. Robinson

Nancy Ross

Ella Rushton

Eleanor Shepard (mother)

Sarah Shepard (daughter)

Elizabeth Shook

Ellen Slattery

Mary Slattery

Robert Smith

Lucinda Truxall

Margaret A. Turney

_______________________________________________

In September 1913, survivors of the Arsenal explosion were gathered at the dedication of a bronze tablet erected by the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. That tablet today hangs in the Allegheny Arsenal Middle School.

It was natural to remember these victims on the 150th anniversary of this event. But I hope that when the 151st anniversary comes 'round, or the 160th, 167th, or the 243rd, that we will pause to remember and honor these folks again.

I also hope that one of the oldest sections of the Arsenal, the powder magazine that dates to circa 1817, will be preserved and maintained as an architectural witness to this tragedy. The magazine now houses restrooms and a maintenance room for the Arsenal Park ballfield and playground, which are today situated near the explosion site.

|

| Allegheny Arsenal Powder Magazine. Source: Wikipedia Commons. |

It is in bad condition and very much in need of repairs. There are three other surviving buildings from the Arsenal complex, but this powder magazine is the oldest and the one physically closest to the explosion.

Sometimes all we have left to honor and preserve from the past are a few names, consecrated dust, and an old empty building. But it is never too late to remember.

|

| My daughter on her middle school Civil War heritage day, 2013. he chose to dress as a young Arsenal worker, not as a southern belle as did most girls in her class. |

______________________________________________

For further information about the Allegheny Arsenal:

1862 newspaper account painted vivid picture of tragedy

184 38th Street

After 150 years, cause of Allegheny Arsenal explosion may never be known

Allegheny Arsenal 150 Years Later (NPR interview)

Allegheny Arsenal Exploded 93 Years Ago

Allegheny Arsenal Explosion and the Creation of Public Memory

Allegheny Arsenal Explosion: Pittsburgh's Worst Day During the Civil War

Arsenal Explosion Recalled by Completion of New Monument

Events to recall Arsenal Explosion

Event to mark 150th Anniversary of Allegheny Arsenal Tragedy (KDKA-TV clip)

Historic Pittsburgh Arsenal Needs Care, Official Says

'Jury' Finds Negligence in Deadly 1862 Blast

Mock Jury Cites Military in Deadly 1862 Allegheny Arsenal explosion

Neglected Lawrenceville park finally has a few friends: Group works toward making 'underused' Arsenal site more inviting

Pittsburgh's Bloodiest Day

Real Heroes Remembered: Allegheny Arsenal tragedy claimed 78 workers in 1862

The Next Page: The Allegheny Arsenal Explosion Pittsburgh's Civil War Carnage

With Allegheny Arsenal Explosion as Background, Consecrated Dust Blends History and Fiction

Women in Civil War Arsenals Project (Facebook page)

Fox, Arthur B. Pittsburgh During the American Civil War 1860-1865. Firefly Publications. 2009.

Frailey Calland, Mary. Consecrated Dust: A Novel of the Civil War North. Dog Ear Publishing. October 2011.

Giesberg, Judith Anne. Army at Home: Women and the Civil War on the Northern Home Front. The University of North Carolina Press. September,2009.

Wudarczyk, James. Pittsburgh's Forgotten Allegheny Arsenal. Closson Press, April 1999. Reprint October 2009.

I am available to present an hour-long lecture about

the Allegheny Arsenal explosion.

the Allegheny Arsenal explosion.

Please email me at historicaldilettante@gmail.com for more information.