|

| 1874 Bird's-Eye View of Pittsburgh, Otto Krebs Library of Congress Collection |

I lost my glasses the other day. It was annoying, but nothing compared to losing an island.

Which Pittsburgh has done at least three times, once in each river.

|

| Pittsburgh's three missing islands can be seen outlined in red on this 1814 hand-drawn map. For details see Darlington Digital Library Western PA Maps, University of Pittsburgh |

The Case of the Missing Island I: Wainwright's Island

If you know Pittsburgh, you know we have rivers. Three of them, in fact. And so of course we have bridges; at last count there were 446. One is called the Washington's Crossing Bridge, although most people call it the 40th Street Bridge because we're literal people here.

But there's also this big honking island in the Allegheny River called Washington's Landing or Herr's Island. It's popularly thought to be the place where George Washington spent a freezing December night in 1753 after he and frontier guide Christopher Gist got dunked when rafting across the Allegheny. Thus the official name of the bridge crossing the island reflects this inauspicious event, and a marker on its southwest side solidly claims the connection:

GEORGE WASHINGTON

A messenger from the Governor of Virginia

to the

commandant of the French forces on the Ohio

and CHRISTOPHER GIST, his guide

crossed the Allegheny at this point on December 29, 1753

on the return journey from Fort LeBoeuf.

Placed by the Pittsburgh Chapter Daughters of the American Revolution

1926

Which would be fine, if it was true. But George Washington likely neither slept here, nor did he cross the river at this point.

According to the accounts that Washington and Gist wrote of their journey, they expected that frozen rivers would be easy to cross as they headed back from their French-scolding mission at Fort LeBoeuf. They were wrong. As Washington later described, about "two miles above Shannopins" they found a barely frozen river filled with ice floes and debris.

Shannopins was a former Lenape village upriver along the Allegheny about two miles from The Forks of the Ohio at today's Point, where Pittsburgh's three rivers meet. Given a lack of archaeological evidence, much debate has taken place as to exactly where Shannopins was. Most agree that it was somewhere along the shore of today's Lawrenceville neighborhood, likely between 31st to 40th Streets bounded by Butler Street and the river. The State Historical Commission commemorates Shannopins at the entrance of the 40th Street Bridge, but that was at best the far edge of the settlement.

Wherever it was, our guys were stuck on the opposite shore, two miles up, somewhere along the edge of today's Sharpsburg neighborhood. And this was not where they wanted to be. A dismayed Washington recalled: "We expected to have found the river frozen, but it was not, only about fifty yards from each shore. The ice, I suppose, had broken up above, for it was driving in vast quantities."

Gist and Washington spent a night and a day planning and building a raft for their crossing. Once launched, their raft caught in the fast moving current, hit an ice flow, and tossed George into the drink. He later recalled:

Before we were half way over we were jammed in the ice and in such a manner that we expected every moment our raft to sink and ourselves to perish. I put out my setting pole to try and stop the raft that the ice might pass by, when the rapidity of the stream threw it with so much violence against the pole that it jerked me out into 10 feet of water, but fortunately, I saved myself by catching hold of one of the raft logs. Notwithstanding all our efforts, we could not get to either shore, but were obliged as we were near an island to quit our raft and make for it.

Gist described their new location as "a little above Shannopin's Town." The two men spent a frozen December night on this overgrown island. Luck was with them the next morning, as the channel between their island and the shore had frozen solidly enough to allow them to gingerly cross on foot.

|

| Mural at Station Square Gateway Clipper fleet tunnel showing Gist and Washington on their raft. |

So whither, island? Apparently verifying the location was difficult even a century later. Neville B. Craig, who published the first comprehensive history of Pittsburgh in 1851, noted a few years earlier in a footnote in his monthly historical magazine that:

...this island must have been Wainwright's, not Herr's. The former island is near the eastern bank of the Allegheny, and that branch of the river might freeze over in one night, so as to bear Washington and Gist; but the wide channel between Herr's island and Shannopin's would scarcely so freeze in one night.Craig had a good point, for the Allegheny is wide and deep enough on the eastern shore of Herr's Island to make an overnight freeze was unlikely.

Alrighty then, so, what of Wainwright's Island? Well, it's gone.

I mean, the land is there, but it's not an island any longer.

While Neville Craig knew it as an island in the mid-1800s, industrialization has since claimed the channel between Lawrenceville and Wainwright's Island that Washington and Gist sloshed across on foot.

The island was named for or by Englishman Joseph E. Wainwright, who settled there with his family circa 1804-06. Wainwright founded a woolen mill on the land and established the Winterton Brewery in 1818 to take advantage of the hops that grew wild along the river banks. The island was quite fertile, hosting hickory, black walnut, locust, sugar maple, butternut, peach and apple trees, plus sugar cane plumegrass. Wainwright described how the channel between the island and the mainland was twenty yards wide, with a fall of about 4 feet. The portion of the Allegheny that flowed into the channel became known to Pittsburgh residents as "Little River," and was regarded as a great spot to catch herring, wall-eyed pike, and bass.

Before Wainwright moved in, the land was referred to as either Cork's or Cook's Island. It has also been referenced by the intriguing name of Good Liquor Island, probably related to the brewery and/or the wild hops that grew there (clearly a happenin' place).

The Wainwrights were not the only settlers on the island. Several prominent Pittsburghers owned property there or on the mainland abutting it, including Conrad Winebiddle (an early landowner in the east end of Pittsburgh) and Mrs. Elizabeth F. O'Hara Denny (daughter-in-law of Pittsburgh's first major, Ebenezer Denny, and daughter of General James O'Hara and Mary Carson O'Hara). Winterton Brewery moved off the island in the mid-1800s and was merged with the Pittsburgh Brewery Company in 1899. But Wainwright's idyllic island didn't even last that long.

A boundary dispute filed in 1868 by Wainwright heirs against a subsequent owner, McCullough, was appealed to the state Supreme Court. It provides some historical information as to how the island was developed. Boats were described as navigating the channel in 1839, but that was no longer possible once McCullough built a dam in 1849 to power his mill. That dam seems to have been a major factor in the dropping of water level in the channel, although at the time of the suit it still seemed to have been partially flowing. A solid road called Allen Street crossed to the island in 1868. Beginning in the Civil War and continuing thereafter, the channel was a dumping ground for building debris and landfill. Whatever wasn't needed at the near-by Allegheny Arsenal or the Carnegie & Phipps Company Union Iron Mill got chucked in the drink. With all the damming and debris, the channel had completely disappeared into the mainland by the turn of the century. Island, no more.

Maps of the era show the island and document its gradual disappearance. (For better resolution images, click on the images, or head over to Historic Pittsburgh Maps Collection to see the original scans I've excerpted). A rare 1830 Barbeau and Keyon map, later reprinted by Johnston & Stockton in 1835, shows the island sitting pretty in the Allegheny.

Lawrenceville insert, 1835, Johnson & Stockton map

This Sidney & Neff 1851 map nicely illustrates the relationship between the larger Herr's Island (aka Washington's Landing) and Wainwright's Island:

|

| Enlargement, 1851 Sidney & Neff map, Library of Congress collection |

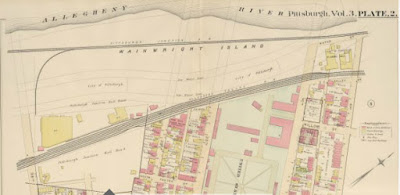

The G. M. Hopkins & Co. 1872 plat map below also clearly shows the island (known as McCullough's for its then-owner). You can see additional Wainwright family property on the mainland, including the Winterton Brewery.

|

| 1872 Hopkins map of Pittsburgh's 15th Ward, including McCullough's Island |

Another close-up of 1872 map. Note property still owned by Mrs. Denny and small industry on island.

By 1890, the strip of land is back to being called Wainwright Island. But it's not much of an island by this point. It appears attached to the shore, although its former boundary was demarcated with a low water line notation.

|

| 1890 G. M. Hopkins & Co. map of Pittsburgh |

By 1900 a pink sliver of land was still labeled Wainwright Island, but was firmly attached to shore.

|

| 1900 G. M. Hopkins map of Pittsburgh |

By 1910, plat maps don't even indicate that this section of land along the Allegheny River between 34th and 40th Streets had a separate name. It does, however, still show up on a Warrantee Atlas from 1914...just barely.

|

| January 1914. Warrantee Atlas of Allegheny County, plate 51 . Western Pennsylvania Maps, University of Pittsburgh. |

Wainwright's Island was gone but not yet forgotten. In 1906, the industries occupying the strip of land over the former channel became involved in a protracted contest with the City of Pittsburgh over who actually owned the in-filled channel bed. The land being disputed was estimated to be about 100 feet wide and 4000 feet long. The City claimed incontestable ownership and viewed the corporations using the land as tenants. Off and on from 1906 through 1919, the City demanded that the companies either pay rent, submit a bid to purchase the land they occupied, or else vacate it. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad/Junction Railroad, US Steel Company, and Allegheny Valley Railroad Company all leased parts of the former Wainwright Island from the city's main tenant, the Denny estate, which did concede city ownership. In all the articles related to these disputes, the land was still referenced as Wainwright's Island (give or take an apostrophe). The former island was still present in living memories of that era. The fact that Wainwright descendants were prominent figures in turn-of-the-last-century Lawrenceville probably helped keep the former island's memory alive, too.

The Case of the Missing Island II: Killbuck or Smoky Island

The Allegheny merges to form the Ohio River a little more than two miles north of Wainwright, and it is there that we find our next set of missing islands...or rather, we won't find them.

The islands were first documented on a 1755 map by Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry, King Louis XV's Chief Engineer of New France. Between 1753-1756, Léry spent time on the frontier building fortifications for the French. In April 1755 he stopped by Fort Duquesne to map its defenses and assess its readiness for the inevitable war with the English. His verdict was prescient: he wrote that Fort Duquesne "....can promise but very little protection..."

Léry mapped the surrounding topography anyway, in anticipation of General Braddock's military advances. The original map is in France at the Centre des Archives d'outre-mer, Aix-en-Provence, Archives Nationales. I unfortunately couldn't find a complete digital copy. However, Historical Maps of Pennsylvania notes that Léry named the Ohio River "Oyo ou Belle Riviere" and the Monongahela "Riviere Manangaile" as can be seen on this map cross-section pulled from Wikipedia:

|

| 1755, Léry's Pittsburgh map. |

What can't be seen above is the part of Léry's map that included an island, just beneath the text to the left. That island became a peninsula when water levels rose, and it jutted from the shores of what later became known as Allegheny City. Two smaller adjacent islands sat to the west.

These land masses, whether singular, triple, or peninsular, were notable features of the terrain and were clearly visible from today's Point (fka Forks of the Ohio). You can see one fat and sassy island on this woodcut map from the January 1759 issue of The Scots Magazine. (See it below #15. Also, note that #6 is Shanapins town). This is occasionally called the first map of Pittsburgh proper, since the English were now in control of the area.

|

| 1759 Pittsburgh |

We can clearly see a peninsula with two smaller islands along the eastern shores of the Allegheny and Ohio below on a "street map of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1795, which includes Fort Pitt." This one was published by Samuel W. Durant in his 1876 History of Allegheny Co. Pennsylvania, so it may be a retrospective creation. Still, the islands are prominent.

|

| 1795 Pittsburgh |

Hugh H. Brackenridge described the island in 1786 in the paper he founded, Pittsburgh Gazette:

At the distance of about 400 or 500 yards from the head of the Ohio is a small island, lying to the northeast side of the Allegheny river, at a distance of about 70 yards from the shore. It is covered with wood, and at the lowest point is a lofty hill, famous for the number of wild turkeys which inhabit it. The island is not more in length than one-quarter of a mile and in breadth about 100 yards. A small space on the upper end is cleared and overgrown with grass. The savages had cleared it during the late war, a party of them, attached to the United States, having placed their wigwams and raised corn there.The biggest land mass, the one described above, was named "Smoky Island." We are probably looking at it jutting out to the left in this sketch by Mrs. E.C. Gibson, wife of James Gibson, a Philadelphia lawyer. The couple passed through Pittsburgh on their honeymoon in 1817. Her sketch has been enhanced, reproduced and colorized many times over since then. The below illustration probably isn't even her original, which appears to have been lost. William Coventry Wall's famous 1877 painting is assumed to have been a close copy of her rendering.

|

| Rendering after a sketch by Mrs. E.C. Gibson, 1817 |

By 1850 the two smaller islands had disappeared from maps and only the peninsula was left. And then just as was done in Lawrenceville, the backwaters were filled with building waste as industrialization took hold of the area's topography by the early 1900s. Island, no more.

But unlike Wainwright's Island, Smoky Island is more vividly remembered in popular Pittsburgh memory. Well, maybe "popular" isn't the right word....ghoulish, more like. Supposedly the island got its nickname during the Seven Years War, when Natives used it to burn English captives there at the stake. According to legend documented by historian Leland Dewitt Baldwin, the Delaware and Shawnee used the island as a place of torture for captives taken following Braddock's defeat in 1755. It was a brilliant tactical choice, as the island was within the sight of French defenders stationed across the river at Fort Duquesne. Whilst ostensibly allied with the French, The Native tribes figured it probably didn't hurt to let them know how enemies were treated. Baldwin recounted a story handed down by young British captive James Smith, who was recuperating at Fort Duquesne and witnessed the goings-on at Smoky Island across the way:

....the prisoners were ferried over the Allegheny to Smoky Island, a low sand bar on the north shore directly across from the Point. There they were tied to stakes or saplings and put to the fiendish torture that the savages could devise. Coals of fire were heaped about their feet; the women thrust red-hot ramrods through their nostrils and ears and seared their bodies with blazing sticks; even the children stood around with their half-sized bows and shot arrows into the legs of the victims. Young Smith, watching from the ramparts of the fort, was so sickened by the sight and by the piteous screams of the dying men that he retreated to his quarters.... ~excerpted from Pittsburgh: The Story of a City, 1750-1865, 1937

Smoky Island gradually became known as Killbuck Island after a chief of the Turtle tribe of Delawares who lived from 1737-1811. Known to his people as Gelemend and to white settlers by his baptismal name of John Henry Killbuck, he initially offered his services to English settlers and then allied himself with the cause of colonial independence. In thanks, Killbuck was given the land known as Smoky Island by Colonel John Gibson during the latter's tenure as Fort Pitt commanding officer in 1781. In a later petition to have his legal rights to the land recognized, Killbuck dictated how that transaction went down:

Col. Gibson....in words to the following effect: "Brother! I put you under my arm; nobody shall hurt you. Brother! I give you this island where you and your children can always plant! The island shall be your sole property." On this he gave directions that a part of the island should be cleared, ploughed, and planted for me with corn, which was also done again in the following years. The grant of the island was afterwards confirmed by General Irwin and his successors the different commanding officers at Pittsburg.

My Brother! This island had long before that time, been considered my Property by all the people of my Nation. And I was now assured that the Governor of Pennsylvania would freely confirm me in that right. ~excerpted from The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Volume X, 1886

Killbuck never did get around to having his ownership legitimized, though he sold the island to one Abner Barker in 1803 for $200 without a Land Office patent to secure his legal rights to the land. Without being able to show legal ownership, Barker apparently decided not to put any money into developing the island. He subsequently lost the land due to unpaid taxes. A several decades-long chain of ownership transfers followed.

Ownership of Killbuck passed to a farmer named David Morgan and his family in 1817, and for a time all seemed well on their island paradise. But in 1820 a fire swept through their cabin while the parents were out, killing all four children. Not a place of peaceful history, this Killbuck Island. Pittsburghers might be forgiven for thinking the area haunted by what a 1949 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article characterized as "....the gray wraiths of so many long-dead Indian and pioneer souls."

A great flood in 1832 took much of the top soil, although it was still intact enough to host a school for boys in 1837. But its viability as an island gradually deteriorated. It was described in great detail in 1874 litigation put forth by heirs of one of the subsequent owners, another case that went all the way to the state Supreme Court:

That's a lot of detail, to be sure (and believe it or not, that's my edited version). Here's why: by 1874 Killbuck wasn't an island any longer. As can be seen on this 1872 Hopkins plat map, the high and low water lines are indicated, but the former Killbuck Island is now seemingly part of the mainland. The roughly 70 yard channel had been filled with excavation and industrial debris.....previously to 1832, there was a small channel at the head of the island, which ran down between that and the main shore, thus forming the island; it was about 100 feet from Bank Lane; the main shore was a perpendicular bluff; the water would be at the base of the bluff about half the year; in dry times the water would not run there. Bank Lane was on the top of the bluff; along some places it was so narrow that a horse could not travel; a man could walk along it; there was a path and a fence some places. At a low stage of water there was a slough only 3 or 4 feet wide....there was always some water when the river was lowest....the higher the water the wider it would be...When there were 5 or 6 feet of water in the river, the whole of the island would be submerged. By a sudden fall in the river, the water between the island and the main land would be left in ponds, between which there would be wide open spaces, so that the place of the channel could be walked over easily; the deepest water was at the head of Killbuck Island; in ordinary stage of water there was a channel; boats would go through; when the river was well up the space between the river and the end of the lots was quite narrow; there was just a pathway around the fences of the lots...The witnesses varied as to the contents of the island from 3 acres to 15 acres. There was evidence that up to the year 1832, Killbuck island was as high as the main land and was never overflowed till then....

Excerpted from 1872 G. M. Hopkins & Co. map of Pittsburgh

Much as with the City of Pittsburgh and Wainwright's Island, the City of Allegheny claimed ownership of this property. In 1874 the ground was leased by the city to the Tradesmen's Industrial Institute for fifteen years. Upon it was built an Exposition Building which opened on October 7 1875.

|

| Advertisement for Allegheny City's Exposition Hall, from Allegheny County, a sesqui-centennial review, 1938 |

The advertisement for this first exhibition, modeled after World's Fairs, noted that goods valued at $50,000 would be displayed:

NOTHING EXCLUDED

Every department will be filled with the most interesting

Inventions and Arts of the age.

Music by First Class Bands

Will be in attendance from 10 A.M. until 10 P.M. during the

entire exposition.

Unparalleled Attractions In Every Department

ALL KINDS OF LIVE STOCK AND FARMERS' PRODUCTS

REDUCED FARES ON ALL RAILROADS

In 1877 the hall came under the auspices of the newly-formed Pittsburgh Exposition Society, and was expanded to 1000 feet long and 150 feet wide. It was a destination that offered great amusement to visitors, but its joys were short-lived. The Exposition Hall on the former Killbuck Island burned to the ground on October 3, 1883. Pittsburgh's newspapers reported that the fire was so fierce that the building was reduced to ashes that afternoon in less than hour. Some 380 exhibitors had goods in the building, many uninsured. Between 300-400 people lost their jobs as a result of the building's demise, and cash from the previous day's record crowds was feared lost in safes in the building. Estimates of damages varied wildly, from $600,000 to a million dollars. Irreplaceable items lost from the "Relic Department" display included an ivory dagger once belonging to Henry VIII and Stephen Foster's piano. Rare coin, clock and book collections were also lost. The World's Greatest Cornetist, virtuoso Jules Levy, feared his golden cornet had melted in the Hall's safe (it was found the next day, somewhat tarnished, but safe). The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette lamented the loss of countless artworks exhibited by local dealers Gillespie and Co., including "....the work of almost every Pittsburgh artist, Hetzel, Wall, Linford, Leisser, Lawman, Turney, among the professionals...It was a collection of almost everything that was known in art, much that was good, much that was bad, but little that had not a high value, either for its intrinsic worth or for its associations."

The papers didn't openly speculate on bad luck associated from the many gruesome losses of life that occurred on Killbuck Island in its early history, but one wonders if the people of the day thought the place cursed due to those early brutal exhibitions. They weren't willing to give up on the land, though, and promptly built a new incarnation of Exposition Park, home field of the Pittsburgh Pirates (then known as the Alleghenies). That field was too close to the flood plain, however, and was abandoned in 1884. The next few decades saw various ownership squabbles over the land, with titles eventually going to a railroad. The land is now mostly a parking lot for the near-by stadiums and casino.

So here's how you save face when your team loses, or you drop your paycheck at the near-by casino: blame it on the accursed fortunes of old Killbuck Island.

The Case of the Missing Island III: That Island in the Mon

Once upon a time, there was a little island on the Monongahela River that never had a name. And frankly, it wasn't much of an island. While land masses in the Allegheny River were formed by glacial till, the Mon was a less dramatic watershed. The island, which sat between the Point and what was then called the city of Birmingham (now Southside), was basically just a big old sand bar that was used as a buckwheat field in the late 1700s. It's clearly apparent in this circa 1760s map of early Pittsburgh (as is the island in the Allegheny):

|

| 1760s Plan and perspective view of Pittsburgh. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division |

In an era before lock and dam construction assured year-round water levels high enough to support riverboat traffic, this island was accessible during times of low water by simply sloshing across the mud-bottomed Mon. And it apparently wasn't even the only such Mon sand bar. This excerpt from an 1826 book describes the Mon island in context of others like it, all situated north of what was then called Braddock's Fording, site of the infamous colonial-era battleground:

Soon after leaving the fording, commence those bars, which are found in the Monongahela, from time to time, until its junction with the Allegheny. The bar at Pittsburgh, is about two miles in length, and from 100 to 250 yards in breadth, and consists entirely of fine sand. The channel is on the side next to the city, which, at the very lowest stage of water, affords a depth of from 5 to 12 feet. ~ excerpt from Pittsburgh in the year eighteen hundred and twenty-six: containing sketches topographical, historical and statistical; together with a directory of the city,

The Mon Island shows up on that 1876 History of Allegheny Co. Pennsylvania map that imagined Pittsburgh back in 1795:

Pitt geologists have speculated that the island only appeared intermittently following major flooding and draining, as implied in the book quoted above.

By 1815, That Island in the Mon is just plain gone from maps. See this Patterson and Darby map from Pitt's Darlington collection:

|

| 1815 Pittsburgh, Patterson and Darby, Darlington Digital Library Collection |

Island no more, unnamed and unmourned.

Some alluvial islands are stable and long-lived like Wainwright's and Killbuck Island, but the Mon island was always transitory. Check out this illustration of the Mon near the Smithfield Street Bridge built by Gustav Lindenthal. It dates to 1885, nearly a century after the first drawing that showed such islands in the Mon. Note the multiple land masses (fluffy ones, too, covered with some sort of vegetation) that were revealed at low tide:

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, from The Pittsburgh Prints from the Collection of Wesley Pickard,

University of Pittsburgh

If the volume or speed of a current changes, alluvial islands get flooded over or can even float away. This is what happened to our Monongahela islands.

Modern Islands in the Stream

Today, Pittsburgh's modern lock and dam system assures that the river currents remain stable. No new islands are likely to appear.

Wainwright's and Killbuck stopped being islands because man willingly allowed the mainland to envelope them. But the land is still there, bearing witness to the history that took place on its soil. If only that dirt could talk, what tales it might tell!

So cool! Thanks!

ReplyDeleteDo you have any information the the First Exposition Building that was on the North Shore? I'm more familiar with the one on the other side of the river that opened in 1889.

ReplyDeletehttp://www.brooklineconnection.com/history/Facts/ExpositionHall.html

I've been gathering photos and info off and about the Exposition history but have much less on the earliest site. It's one of many side projects of mine and I hope to write about it eventually, even if it's just a small Facebook blog. I can tell you that the Pittsburgh Exposition Society was formed in 1877, taking over where the Pittsburgh Trademan Industrial Institute left off. The first fair was later in 1877 on the Allegheny City grounds of the PES (now Pittsburgh's North Side) at South Avenue and School Streets.

DeleteI enjoyed reading this, and found it well researched and interesting. I actually linked to it on my blog (http://mappyplace.blogspot.ca/2018/03/pittsburgh-in-1795-and-1876-and-forts.html) where I discussed an antique map I have of Pittsburgh and which you used in your research. You taught me a bit more about my map, and about Pittsburgh. I appreciate it!

ReplyDeleteLucky you to have a copy! It is indeed a charming map for the reasons you mentioned, the respectful self-awareness of past and present.

DeleteI feel luck to have it! That said, I'm not sure how rare it is. I bought mine in Pittsburgh. I'm sure there are others out there!

DeleteIt may not be valuable as a rarity, but it's still a treasure!

DeleteI have done some archaeological work in the area. It looks to me that they filled in backchannel and not the island is actually land.

ReplyDeletePatrick Riley

rmadanthony@aol.com

Thank you for the interesting article. My 3rd great grandfather, Thomas Stout spent much of the Revolutionary War on an island "...where the Monongahela and Allegheny meet to form the Ohio" as a spy reporting on the English and Indian allies. I was hoping to be able to decide which island it was but guess it is back to more research. His service on one of those islands did get him a Revolutionary War pension in the 1830's. Thanks again, very interesting.

ReplyDeleteFascinating. Thanks!

ReplyDelete