|

| Elephant trade card issued for Allen & Ginter brand cigarettes, 1890. The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick, Metropolitan Museum of New York. |

Okay, I’m exaggerating.

But Edward Bigelow really did want an elephant. And what Edward Bigelow wanted, Edward Bigelow usually found a way to get.

_______________________________________________________________

Someone told me it's all happening at the zoo...

|

| Edward Bigelow Palmer's Pictorial Pittsburgh, 1905 |

These parks got poppin’ in 1889 when Bigelow outmaneuvered a real estate developer by convincing Pittsburgh heiress and expatriate Mary Schenley to use her family’s land to create a city park. She agreed to donate 300 acres of land from her family’s estate for that purpose, with an option for the city to buy 120 more. She also included a stipulation that the property could never be resold, and that the resulting park was to be named for her.

It had taken nearly two decades of roundabout discussions to get to this point and the Pittsburg Press rejoiced on behalf of Pittsburghers: “It is the place of all places in this city for a park, and if Chief Bigelow gets half a show, he will make a breathing spot of which Pittsburg may be proud.”

Indeed, Bigelow set to work immediately to shape that “breathing spot.” He hired crews to blast, grade, plant, and create bridle and walking paths through the “rugged, airy place.”

|

| Workers creating a bridle path in Schenley Park, March 1908 Pittsburgh City Photographers Collection, University of Pittsburgh. |

Such work would continue well into the new century, criss-crossing Schenley Park with roads, rustic bridges, and trails. The park would eventually boast a horseracing track, lakes, ponds, picnic areas, a music pavilion, sporting fields, and a golf course. And within a few years, industrialists Henry Phipps and Andrew Carnegie added value to the area by building their eponymously named plant conservatory and library/museum complex on the park fringes.

But in the beginning, Bigelow needed to find a way to encourage the public to visit this barely tamed wilderness. So…why not build a zoo?

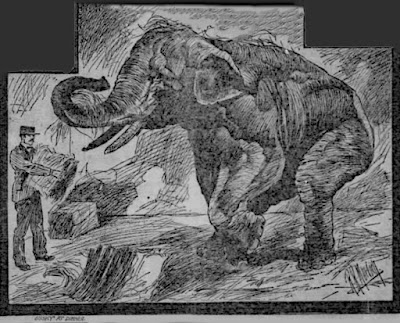

|

| Cartoon showing Bigelow imagining his Schenley Park zoo. Pittsburg Press, 27 April 1890 |

Pittsburghers responded by enthusiastically donating critters. By August 1890, nine months after securing the land for Schenley Park, Bigelow found himself in possession of quite a menagerie. The inventory included two bear cubs, various red foxes and raccoons, a covey of prairie chickens, two “diminutive” donkeys, some bald eagles, and a “family of chameleons.” He also had a flock of South Down sheep on order, for that all-important pastoral aesthetic (and lawn maintenance).

Still, when it came to funding the new zoological park, Bigelow’s ambitions outstretched his resources. He didn’t exactly have a line-item appropriation to house and feed these animals (although that prairie chicken flock may have taken care of the foxes’ needs).

Bigelow also did not have an elephant for his zoo.

And he really wanted an elephant.

This obsession with getting an elephant wasn’t unusual for the time. Variety indicated a superior menagerie, and captive elephants were the pinnacle animal to have in a 19th century zoological collection. Pittsburgh’s local papers teased that the owner of a traveling circus was willing to sell his older male pachyderm for $3000 (about $60,000 today). Who knows if that was the going rate for an elephant, but it was apparently too spendy for Bigelow or his potential donors. Pittsburgh Daily Post claimed in July 1890 that a “certain gentleman” was willing to shell out less than half that amount, some $1200, for an elephant for Pittsburgh.

That gentleman was most certainly a Pittsburgher named Levi DeWolf. He had placed what amounted to an elephant want ad in the New York Clipper, whose masthead proclaimed it the “oldest American theatrical and sporting journal.” DeWolf’s ad was placed in late June 1890 and ran for two weeks.

|

| Elephant want ad for Pittsburgh's new zoo. New York Clipper, 5 July 1890 |

Although he was not identified as such in the newspapers, DeWolf was the brother of Esther Gusky, the widow of Jacob Gusky of local department store fame. Gusky’s Department Store was one of the first modern retail mega-successes of its kind in Pittsburgh, and it had made founder Jacob a wealthy man. Jacob was also a very generous man, and the city benefited from his hands-on philanthropy to the poor and working classes. He was particularly beloved for sponsoring toy-laden Santa visits to all the local orphanages on Christmas Day. When Jacob died at the age of 41 in 1886, his wife Esther vowed to continue his acts of public and private generosity. So her brother Levi DeWolf was acting as her agent in seeking an elephant for Pittsburgh’s zoo.

But newspapers cautioned Pittsburgh not to get its hopes up about the possibilities:

It is a very easy thing to promise an elephant to the park, but it is no means easy to buy one. Good elephants are not plentiful in this country, and people who own those that are here want enormous prices for them. One or two answers to the Clipper’s advertisement have already come in, but as yet nothing has been found that is satisfactory. Something will be found eventually, however, and ere the summer is over an elephant, tall and stately, will hobnob with the bears and burros and foxes of the Schenley park zoo. ~Pittsburg Press, 7 July 1890

Lo and behold, the ad worked! It was announced in August 1890 that DeWolf had procured a “baby” elephant for the Pittsburgh zoological garden from a New York animal dealer named Donald Barnes. DeWolf explained to the Commercial Gazette:

I had wanted a baby, believing the changes of climate would not affect a young one as much as an old one, and that he would gradually become acclimated. Another reason was that a young one would be tame and could be trained to ride the children around the garden, as is done in the Philadelphia “Zoo,” and by changing five cents for a ride there might be a source of income to help if not entirely bear the expense of keeping up the garden. The idea in purchasing so expensive an animal as an elephant was that by starting the ball rolling other business houses might be stimulated to contribute an animal or two, and thus the city could have a collection of animals without it costing the taxpayers a cent.

No one knew how much of his sister’s money DeWolf spent for this elephant. One paper said $3500, while another said $2200. But, really, what price could be put on the joy an elephant would bring to Pittsburgh?

And anyway, good elephants were hard to find.

This one was initially described as a five-year-old male from India. An Asian elephant of that age is basically an early elementary school child, only just transitioning from dependency on its mother. The Press assured readers that this elephant was “…thoroughly tame. He had been used for a year or two as a beast of burden and is said to be as gentle and kind as a kitten.” The Pittsburg Dispatch concurred, noting that the elephant was “….5½ feet high and is well trained. He is said to be very gentle, and his last owner on the “coral strands” recommends him as docile and very fond of children.”

|

| Illustration of rugged Schenley Park in 1890, including free range sheep. Pittsburg Bulletin, 8 November 1890 |

Pittsburgh would have to wait several months for its “tame” elephant to arrive from India. Meanwhile, despite Bigelow’s ambitions, Schenley Park remained a rugged tract. Lasting improvements to make the park accessible were expensive and time-consuming, but local papers still encouraged people to visit.

It was a hard sell. But hey, at least there was a zoo!

Sort of. The Press damned with faint praise:

You can visit the zoo, Chief Bigelow’s happy family. To be sure, the elephant hasn’t arrived yet, and the tigers and lions are still roaming about the wilds of Africa, but the two cub bears are there. So are the two diminutive donkeys and the big eagle that stands majestically on a fence rail and screeches for liberty and the land of the free every time anybody approaches. These are there already, and the presence is a guarantee of good faith that the rest will show up in good time.

You could visit the zoo, sure, but what you'd see was a ramshackle assortment of wooden shacks populated by random animals. Society newspaper The Bulletin laid it out:

In fact the zeal of Pittsburghers to contribute some strange bird or quadruped to the Schenley Park “zoo” has been embarrassing to Mr. Bigelow and his assistants. There are as yet no adequate or suitable buildings for the housing, even in the summer, of the animals provided, and until this is the case, the Schenley Park collection must retain its rudimentary and somewhat melancholy form.

According to a 1943 history of Pittsburgh’s public parks, the zoo was at the top of Panther Hollow across from the merry-go-round, which would put it somewhere in the vicinity of today’s Bartlett Playground. It was so unimpressive in 1890 that some scoffed at its pretensions, as per this mocking piece in the Pittsburg Press:

So the ruler of the department of public works….waxed great and his heart was lifted up within him. And he said within himself, I will build a zoo, and it shall be called Chief Bigelow’s zoo, and shall contain beasts and birds and reptiles, both wild and tame… So the word went forth and the friends of the people gave gifts. And the same were valuable, and some were duplicates, and some were suffered to escape. And those that remained were taken and placed in the middle of a wide desert waste called Schenley park, and people took horses and carriages and risked their necks crossing the railroad to go and see them.

By mid-October 1890, with the promised elephant nowhere yet in sight, the other zoo animals were moved from their shacks in Schenley Park across town to “winter quarters” in the former Fifth Avenue Market House. This was a long, one-story, wooden multi-purpose building on the corner of Fifth and Miltenberger streets (destined to be demolished a few years later so Fifth Avenue High School could be built).

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 15 October 1890 |

The apartment to be occupied in the old market house has been suitably arranged for the animals, cages having been built in tiers along the east wall. Conveniences for cleansing the cages and apparatus for heating the room have been put in, and the animals will have excellent winter quarters. There is at present no suitable place in the park for taking care of the zoological collection….The elephant donated by Mrs. Gusky is expected to arrive within a few days. Mr. Bigelow was notified that it is on the way, and he is expecting its arrival daily. When the elephant comes he will at once be housed in the market house for the winter. Chief Bigelow will probably make arrangements to have the new menagerie open to the public between certain hours on certain days of the week.

One month later on 16 November 1890, Levi DeWolf traveled to New York City to fetch his sister’s elephant, fresh off the steamer ship Delcorno.

DeWolf soon realized that bringing the beast back to Pittsburgh was going to be more complicated than anticipated. A custom-fitted howdah, or canopied carriage, was needed so Pittsburghers could ride on the back of their new elephant. There were no expert howdah makers in Pittsburgh, so DeWolf had to arrange for his new elephant to be fitted in Manhattan before bringing it home.

| |

| Levi DeWolf, 1858-1915 Notable Men of Pittsburgh and vicinity, 1901 | |

Levi may have wearied of all things elephant by this point, but the newspapers were having fun. The Commercial Gazette let Pittsburgh know what awaited the new elephant at the zoo:

….the whole establishment was stirring with the progressing preparations for the reception of the Gusky elephant, which will arrive from New York this evening. A room was being fitted up and the pachyderm will have an exclusive apartment entirely separated from the fierce sheep and donkeys. He will not be inducted into his new home, however, until the latter part of the week. In addition to the other furnishings of his apartment he will be provided with a stove, and efforts will be made to keep him comfortable with the semblance of an Indian temperature. The many attentions the elephant will receive from all indications will tend to make him conceited unless he possesses strong Democratic ideas. The latest importation from farther India is five feet six inches in height and weighs 5,600 pounds. He is eight years of age, and is still only an infant as elephants go. When he has had time to expand and rise he is expected to become great in proportions as well as in fame.

Yes. You read that right: in these newspaper accounts, the elephant had aged from 5 to 8 years in a matter of months. Who knows if any of the reporters had their facts straight? Then again, perhaps a different elephant had been sent.

Or maybe no one really knew anything about what they were doing.

|

| Cartoon in Pittsburg Press, 26 October 1890 |

This maybe five-year-old, maybe eight-year-old elephant traveled on a freight train from Manhattan to Pittsburgh on 19 November 1890. Somewhere along the way the elephant officially acquired a name: Gusky. After being unloaded at the Duquesne freight station located at the Point, Gusky immediately became the star attraction in a parade, led by a brass band. This parade snaked through Downtown and detoured past Gusky’s Department Store at Third and Market Streets (where the PPG glass castle complex is today), then marched straight up Fifth Avenue for about a mile to the old market house. The Press commented on the “diminutiveness” of the elephant, which was referred to as a “baby.” The paper assured concerned readers that “Comfortable quarters have been prepared there, and a long winter’s rest with plenty of food will probably overcome the bad effects of the ocean voyage.”

Bigelow got his elephant. All of Pittsburgh rejoiced. And Gusky the elephant lived happily ever after.

Right?

Right???

You can stop reading here if that’s what you’d like to believe.

|

| Excerpts from article welcoming Gusky in Pittsburgh Post, 20 November 1890 (Note illustrator's artistic license giving Gusky tusks. Only some male adult Asian elephants have tusks). |

_______________________________________________________________

It's a light and tumble journey from the east side to the park...

The first elephant to arrive in the United States was the Crowninshield elephant in 1796, named for the ship captain who brought him from India to Massachusetts. Less than a decade later in 1804, a female Asian elephant arrived. She was purchased a year later by New York farmer Hachaliah Bailey, who named her Old Bet. Bailey made Old Bet the star of a traveling menagerie that toured the East Coast.

Such captive displays of these enormous creatures were, well, enormously popular. Decades later, Hachaliah’s distant nephew James A. Bailey partnered with a fellow named P.T. Barnum to add performing elephants to a traveling circus.

|

| Captive elephant illustration, Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 29 November 1890 |

Getting an elephant across the mountains of Pennsylvania would have been a daunting task. The first elephant thought to have visited Greensburg and Pittsburgh was a male named Columbus, also owned by Hachaliah Bailey, in 1819.

|

| An 1819 advertisement for the first elephant to visit western Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh Gazette |

Today we understand that elephants are self-aware, emotionally complex creatures who form intense familial and community bonds. Female elephants in the wild live their entire lives within close-knit family groups, and males can stay with their herds into their second decade of life before embarking on solo bachelorhood. Elephant herds can contain more than 50 animals, and the creatures are nomadic by nature.

And today we recognize that placing elephants in captivity results in significant mental and emotional harm for the animals. Restricted space and limited opportunities for exercise, constant stimuli of visitors and noises, and wooden, metal and concrete man-made housing can cause debilitating stress. The resulting trauma is manifested in what is called stereotypic behavior that includes rocking, swaying, pacing, weaving, and head-bobbing.

Mahouts are the traditional handlers who work with captive Asian elephants. Most forge deep emotional bonds with the animals under their care. Their informed relationships with elephants help mitigate damage from living in captivity, and their expertise is often based on generations of traditional familial knowledge passed down from fathers to sons (and occasional females). For centuries, mahouts accompanied elephants given as gifts to European rulers.

|

| Royal elephant with mahout c. 1660. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. |

There was no mahout accompanying Gusky the elephant to Pittsburgh in 1890. If there had been, the mahout could have immediately set Pittsburgh straight about one important detail: contrary to all published reports, Gusky was a girl. You wouldn’t think it would be that difficult to figure this out once Pittsburghers laid eyes on the elephant. But for decades afterwards, even though the city realized it had a “lady elephant”, local newspapers would still refer to Gusky as a male.

Workers at Pittsburgh’s Schenley Zoo in 1890 had never handled an elephant before, but no one seemed worried about the lack of experience. The philosophy was that elephants were basically really big cows who had appendages of unusual size and if you could handle livestock, you could handle an elephant.

Boy or girl, baby or juvenile, the city was nonetheless wildly excited about its elephant’s arrival. Pittsburgh City Council adopted an official resolution on 8 December 1890 to thank Mrs. Gusky for gifting an elephant for the Schenley Park zoo.

|

| Pittsburgh City Council resolution from Pittsburgh Municipal Record, 1890, no. 724 |

Gusky managed to survive the stress of marching through the city behind a brass band and was made to feel at home (according to 19th centuiry Pittsburgh standards) at the old Fifth Avenue Market House. She remained there for nearly six months, during which time visitors came from far and wide to gawk and marvel. On 2 May 1891 it was announced that she would be moved soon to the newly refurbished Schenley Park zoo. Workmen had made considerable progress at building roads and otherwise civilizing the park -- or at least enough progress that it was deemed suitable for an elephant. Gusky’s transfer was accomplished quietly later that month in the early morning hours, without a street parade to mark the occasion. By mid-June, she was keeping cool in the city heat by flapping her ears and tossing hay around, much to the amusement of visitors.

At Bigelow’s suggestion, a likeness of Gusky was featured in the gala July Fourth fireworks display at Schenley Park. Pittsburgh would have oohed and ahhhed as the twinkly elephant moved her ears and trunk “in process of combustion” in the night sky.

You know you’re famous when you’re included in a Pittsburgh fireworks display. But let’s face it, major pyrotechnics aren't an elephant's choice of a good time. We can assume Gusky wasn’t at all impressed by the explosions in her backyard, and in fact was probably terrified by the noise.

It’s not clear whether Gusky earned her keep by giving rides in the new Schenley digs right away, but in 1894 the Pittsburgh Post announced that Esther Gusky had donated a “fine big saddle” for Gusky that could carry eight children. She also donated livery for the elephant’s keeper so everyone looked spiffy. Rides on Gusky cost 5¢ each.

In these early years, Gusky was also occasionally taken from the zoo to participate in community street parades. On one occasion in 1896 she bore two riders dressed like clowns, who may have regretted that particular life decision: “They looked anything but jocular, and the expression of fear made it extremely ridiculous,” wrote the Commercial Gazette.

In September 1895 another elephant was loaned to the Schenley Zoo. This was a mature female circus performer with the undignified name of Miss Dazzle who was allegedly 80 years old. Given the shortened life spans of captive elephants, Miss Dazzle was most certainly not 80 years of age. But at the time conventional wisdom held that elephants lived to be 100 years old, so it was assumed that Miss Dazzle was quite the grand dame.

What was indisputable was that Dazzle dwarfed Gusky in size. Gusky was still described as a “baby” and her diminutive size charmed rather than awed Pittsburghers. The press was fascinated by the “monstrous” Dazzle and speculated that she was the largest elephant currently in captivity.

Although it’s possible that Gusky may have “met” other elephants passing through Pittsburgh in circuses, it’s more likely that Dazzle was the first of her species that the little elephant had a chance to engage with since coming to Pittsburgh.

These headlines and Pittsburg Post excerpts set the elephants up for conflict that didn’t exist:

|

| Pittsburgh Post headline excerpt, 30 September 1895 |

Miss Dazzle was introduced to Miss Gusky without any formalities, and the two great brutes behaved very becomingly. Each displayed more or less of the curiosity characteristic of the sex, Gusky being particularly inquisitive in the matter of sizing up her guest, but without any unmannerly demonstrations. Last night the keeper said they were apparently well satisfied with each other’s society, and no trouble is anticipated if discretion is shown by the attendants in not rousing Miss Gusky’s jealousy by undue attention to the monstrous Miss Dazzle.

Dazzle, thought to weigh some 9,000 pounds, immediately became a star attraction. Reporting a week after her arrival, the Post seemed bemused that the elephants were actually getting along:

Gusky was the queen of the zoo until the arrival of Dazzle, but the latter seems to absorb the major share of attention, and the strange part of it is that Gusky isn’t showing the least symptom of that jealousy, which carping and ill-natured critics always ascribe to the sex. She has, in fact, taken quite a liking to the dazzling creature that shares her lodging, and Superintendent Burke says that the “baby” shows a great deal of uneasiness when Dazzle is led out for a promenade or to get a drink of a few tubfuls of water.

What we’ve since learned about elephant behavior explains that the isolated juvenile Gusky recognized the older Dazzle as a dominant matriarch. Having been on her own for nearly five years, she seems to have been content and even happy to hang out with Dazzle.

The elephants were moved into a large, heated barn at Schenley Park for the winter months. It must have been close quarters since the barn also housed the zoo’s lions. While Schenley Park continued to expand, Gusky’s living circumstances were not part of the overall improvement plan. For instance, in April 1896 the Commercial Gazette published a feature story about Sunday afternoon in the parks. It included a haunting description of what life was like for the now 11-year-old elephant. Despite free peanuts and apples tossed by visitors, living conditions for Gusky and Dazzle (misnamed Basil) were hardly ideal:

|

| Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette headline, 13 April 1896 |

But poor Gusky, the elephant that delights the hearts and elevates the minds as well as the bodies of children, was almost neglected. She is stationed in a low, dingy shed -- a good home in everything but the distance from her visitors. She was too far away from the chain to be fed with peanuts or apples, but Basil, the huge elephant loaned the park, had every opportunity to get filled to repletion. She was too stingy, however, to save anything for Gusky and the latter is still hungry. Next Sunday Gusky will be taken from the shed, surmounted by a howdah and given a chance to gain the appreciation of boys and girls by carrying them on her back. The other elephant has no howdah, nor is it likely she will get one. This is where Gusky gets square.

An elephant was usually held captive by means of a chain around one of her legs that was in turn connected to the ground. The Schenley elephants were thusly tethered and displayed in a pen, separated from the public by a barrier chain.

It's not clear how long Dazzle remained with Gusky. They may have only been together for a few months, until circus season started again in the spring. At that point Dazzle would have been reclaimed by her owners and taken on the road to dazzle audiences, leaving Gusky alone and isoalted once again.

Gusky did occasionally get relief from the confines of her pen and tether. An April 1897 Daily Post article described how she was led on daily walks along trails in Schenley Park.

That's right: Gusky took a daily constitutional in Schenley Park.

She didn't seem terribly enthused about the stroll, however, and kept twisting her head to look around nervously. Eventually it was determined that Gusky's hypervigilance was due to being stalked by a fierce free-range billy goat from the Four Mile Run area.

This goat had an agenda:

….the goat would slip up the hill behind Gusky and butt her on the legs. This happened daily for a long time, and every effort of the elephant and her keepers to stop the nuisance was of no use. But Thursday morning the culprit was captured. Gusky turned around just as the goat was breaking for her. The buck had a good start and was advancing at full speed. The speed was so fast that the animal could not stop and the victim ran right into Gusky’s trunk. The elephant lifted its tormentor into the air and, with a great swing, threw the goat far down the hillside into the ravine. As yet no one has ever taken the trouble to learn whether the goat was killed or not.

Gusky was, seriously, the G.O.A.T.

_______________________________________________________________

Just a fine and fancy ramble to the zoo....

In 1895 Bigelow's coustin and local Republican political boss Christopher Lyman Magee made the first of two donations ultimately totaling $125,000 to create an expanded, modern zoo. “No more interesting or instructive institutions can be found in the great cities of the world than the Zoological Garden,” wrote Magee when he announced his donation.

This zoo was to be built across town from the old zoo at Bigelow’s pet project, the new Highland Park. Bigelow needed to attract people to the park, which not co-incidentally was at the terminus of new trolley lines that his cousin Magee owned major interests in. There was thus certainly personal incentive at play, since creating destinations of public interest like parks and zoos would encourage Pittsburghers to use the revenue-generating transportation infrastucture. Bigelow also recognized that to hold its own among other 19th century urban centers, Pittsburgh needed something grander than the shabby old Schenley Zoo.

|

| Schenley Zoo from Pittsburgh Exposition, 1894. Western Pennsylvania Exposition Society. |

Reports about the condition of Schenley’s elephant house illustrated how horrible things had become. Despite the best efforts of cats kept on the premises for rodent population control, and copious application of poisons, rats had overrun the place. A rat colony nested in the sawdust insulation layer between the double walls of the wooden frame buildings. They emerged at night to steal food from the animals -- and to torture Gusky. “Several times they caused Gusky to become panic-stricken,” wrote the Pittsburg Post in May 1898. “The big elephant refused to lie down at night out of fear of their attacks. On one occasion they chewed the calloused skin from her feet.”

|

| Schenley Zoo elephant house. Pittsburg Post, 12 June 1898 |

Thankfully for Gusky's toes, a new and improved zoo was planned consisting of a long, tall, imposing one-story building with two wings, to be designed by Chicago architect J.L. Silsbee.

|

| Highland Park Zoo postcard, c. 1903 |

Sitting atop a denuded hillside in Highland Park, the building was reached via a 120-foot terraced staircase. The elephant room to the left of the eastern entrance was a “great, airy, well-lighted and well-ventilated” room 80 x 45 feet and 12 feet high, with skylights, cement floors, and enameled tile wainscotting. Pipe rails divided the room, marking space for three elephants on one side and other large animals yet to arrive on the other, possibly including a giraffe. The lions lived one room over.

|

| Highland Park Zoo c. 1900. Carnegie Museum of Art Collection of Photographs. |

On opening day 14 June 1898, Gusky was the zoo’s sole pachyderm. That would soon change. Four months later in October, two more elephants and two elephant specialists arrived at the new zoo.

|

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 3 November 1930 |

An interview Tretow gave to the Press upon assuming his duties in October 1898 revealed his philosophy about working with elephants, his favorite animal:

The elephant even in it haunts is not a fierce beast, unless he is injured, and he then becomes very savage. In training all animals we always try kindness first, using all sorts of inducements to get the beasts to obey you. When this fails we are compelled to bring the whip into play. The latter, however, is not a good thing, as it often angers the subject and he is then less likely to do your bidding. It is not difficult to train an elephant, and although they are very large and heavy, they can be trained to almost anything. The native is the best adapted to train the beasts, as the animals seem to understand their speech better than that of any other person. In the training of the elephant all that is needed is a little patience and the result will be pleasing. The animals really display intelligence.

With Tretow came Cetoua (sometimes written as Cetona). He who was described as a “cornack,” which was another term for mahout. The papers described Centona as Cingalese, from Ceylon. Today we understand that he was a native of Sri Lanka, an island south of India. But to 19th century Pittsburghers, Cetona was so exotic that he might as well have come from another planet.

|

| The mahout Cetoua, Pittsburg Press, 28 October 1898 |

Pittsburgh papers were as fascinated by Cetoua as they were by the new elephants, and were especially bemused by his fashion and footwear preferences. Readers were treated to regular updates about whether Cetoua wore shoes or stockings, and one paper shared his assertion that “shoes gave him corns.” This excerpt from a Press article is typical of the wonder and 19th century judgement that Cetoua faced upon arriving in Pittsburgh:

Mr. Tretow took the Cornack to his hotel, but the man attracted so much attention that the proprietor put him out of the house. The only English word that he knows is money. He smokes cigarettes almost constantly, and rice is his principal article of food. He puts a handful of cayenne pepper and a handful of salt into his rice. He is averse to wearing shoes and stockings. A pair of shoes and stockings were purchased for him yesterday afternoon, but when they were handed to him he threw them out of the building. He became homesick as soon as he arrived in the city and wanted to start for his home yesterday afternoon. However, when he was taken to the zoo he became contented. He was informed that his photograph would be taken. He went into the zoo building and arranged his toilet by washing his feet. He did not put any water on his face.

Ernest Tretow and Cetoua took charge of an expanded Pittsburgh elephant collection that included Gusky and newcomers Punchy and Phoebe.

|

| Elephants identified as Punchy (left), Phoebe (center) and Gusky (right) by zoo. Image from The Pittsburgh Zoo: A 100-Year History, 1998. |

Punchy was described as a large female weighing 6,000 pounds who was nearly two feet taller than Gusky. She was thought to be near 50 years of age.

Cetoua met Punchy’s train at the East Liberty rail station and startled the neighborhood when he jumped on the elephant’s back and rode her two miles to the new zoo.

|

| Illustration of Cetoua riding Punchy through East Liberty and Highland Park. Pittsburg Press, 30 October 1898. |

Punchy came to Pittsburgh via Hamburg from her native India, where she was a beast of burden and hard labor. A 1900 Pittsburg Post article described conditions in her native land: “There they work elephants in the rivers moving lumber. They wade into the water and handle great logs with their trunks. Punchy served an apprenticeship at this. Her growth has been stunted by her early hardships.” We can’t know if Punchy’s growth had been stunted, but Tretow had no qualms about continuing to use her for labor. The same article detailed how Punchy helped workmen by yanking out multiple zoo fence posts sunk six feet into the ground: “Punchy cleared the whole ground of posts last week, and never said a word. There was no bossing of a gang of men with profuse profanity. She just wrapped her trunk around a post, and yanked it out….”

Punchy was the gift of Christopher Lyman Magee and wife Eleanor. The other new elephant was named Phoebe, although she was sometimes listed as Bebe. Like Punchy she arrived in October 1898, but received much less press coverage so archival information about her is limited and, frankly, conflicted. For instance, in photos from this period (see below), the elephant identified by the Pittsburgh Zoo as Phoebe has pronounced tusks. That's typical only for some male Asian elephants, not female ones. It's possible this identification was a mistake, and perhaps there was actually another male elephant present around this time who was either an Asian male or even an African elephant. It was once thought acceptable to mix Asian with African breeds, although this is no longer done due to concerns about EEHV virus transmission.

On the other hand, maybe Phoebe was renamed Bebe upon arrival when it became apparent that she was a he! According to limited contemporary press coverage, Phoebe was smaller and presumably younger than Gusky. In some sources she (he?) was also noted has having been a donation from the Magees.

In the way that elephants do, these three may have formed a family unit at the zoo, sharing close quarters in the new building. There were no press reports of conflict -- and since elephant fights made for good copy, we have to assume they sorted out any relationship difficulties.

|

| Ernest Tretow poses with three elephants, c. 1900. Possibly Punchy is to the right, Gusky lying down at center, Phoebe on left. Image from The Pittsburgh Zoo: A 100-Year History, 1998. |

The elephants were brought out to perform stunts and tricks for visitors at 2 PM each day. Punchy was the most skilled, but Gusky was a fast learner and Phoebe seemed eager to try.

|

| Ernest Tretow with a trained elephant, c. 1900, probably Punchy. Image from The Pittsburgh Zoo: A 100-Year History, 1998. |

But this family unit didn’t last long. Phoebe or Bebe died of “acute stomach trouble” in November 1900. Her (his?) hide was donated to the Carnegie Museum. Punchy died two years later in March 1902 of what was termed “old age.” The newspapers recounted the challenging task of removing her remains from the elephant house, and spared no detail about dismemberment for preservation and display at the Carnegie Museum. There were even pictures!

|

| RIP, Punchy. Elephant being skinned for Carnegie Museum collection. Pittsburg Post, 16 March 1902 |

Were the elephants assassinated? As wild as that seems, the turn of the century was an unsettled time at the zoo. Querulous Superintendent Bigelow, always primed to go public with grievances should he feel slighted, made a sensational claim in 1904 that an unnamed city employee critical of his policies had embarked upon a campaign of poisoning various zoo animals -- including the two elephants! However, that assertion soon faded without evidence.

But then Cetoua left. Claiming homesickness, he returned to his home in Ceylon in 1899. The papers claimed he had a contract and was going to return to settle in Pittsburgh with his family, but he was never seen again.

Our girl Gusky was on her own once more.

_______________________________________________________________

And the elephants are kindly but they're dumb.....

After Punchy’s death, the newspapers began remarking on Gusky’s behavior.

So Gusky remains the only resident of elephantine proportions in the parks.

Gusky, who was first to come and who was thought at one time not long for this world. Visitors to the zoo have noticed the envious weaving motions Gusky makes with her head. It gets on one’s nerves to watch her, and it is a nervous affliction common to many elephants. Weaves is the popular name and chorea the scientific.

When E.M. Bigelow was director of public works Gusky developed the complaint. Mr. Bigelow was disappointed in the animal, and, fearing that she might not stay long within our midst, consulted the animal trainer of Barnum’s circus. The trainer made a trip to Schenley park, where Gusky was then domiciled, and after examining her elephantship pronounced her sound in every other respect, predicted a long lease of life, and said that many circus elephants had this same complaint in a much more aggravated form, stamping one foot in unison with the head motions. So it is comforting to know that in spite of Gusky’s nervousness she bids fair to “remain in our midst” for some time to come. ~Pittsburg Post, 16 March 1902

What the above excerpt makes clear is that those manifestations of anxiety -- what animal specialists today would recognize as stereotypic captive behavior -- began when Gusky was still a very young elephant living at the Schenley Park Zoo between 1891-1898. By the time the Post article was written in 1902, Gusky was thought to be 15 years of age.

Her vigorous head-swinging was commented upon again by the Post in 1907:

Gusky, the lone elephant of the zoo, continues to move her head to and fro as if rolling with the waves. It is a well-known fact that practically all animals in captivity indulge in some kind of perpetual movement. The theory has been advanced that Gusky’s movement was acquired while she was crossing the ocean in a ship.

|

| Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 16 November 1915 |

Although they could not explain the causes, experts of the era recognized that even in an otherwise healthy animal, such repetitive behaviors persisted unless circumstances improved. Even if additional stimulation was added, it would be difficult to completely extinguish the behaviors once they’d become as habitual as Gusky’s had.

Gusky's steady deterioration in captivity was painful for Pittsburgh to observe. In 1915 when potential appropriations to improve the zoo were discussed, Gusky’s situation was specifically cited, but nothing was done to consistently and effectively improve her situation.

The Director of Public Works in 1918 told the zoo to put Gusky to work by harnessing her to a plow in the city’s war gardens. To their credit, zoo officials insisted this could not be done. The Post report further detailed how untenable her situation had become, noting that Gusky “…is tethered closely four ways, and this is the only way they can keep her, the keepers say. For years the Pittsburgh public has viewed the elephant—always tied up tight.”

For better or worse, Ernest Tretow was at least a constant presence as Gusky’s keeper. He remained with the zoo until resigning in 1922 over a salary dispute (although he would later return). He did his best to care for Gusky, but his methods were primitive by today’s veterinary standards. The papers would occasionally inform readers about Gusky’s corn removals, callus trimming, and biannual manicures done with chisels and hammers. The elephant’s podiatry woes were likely made worse because of limited freedom of movement and the cement flooring.

|

| "In the Manicure Parlor at the Highland Park Zoo." Pittsburgh Gazette Times, 22 April 1915 |

There was also considerable interest in how much Gusky ate and drank.

|

| "Gusky at dinner." She was apparently so well-fed that she grew tusks... Pittsburg Gazette, 17 Nov 1901 |

|

| The Plain Speaker, 26 September 1922 |

There were unsuccessful attempts to permanently expand Pittsburgh’s elephant collection after Phoebe and Punchy died. But other than an occasional loaner elephant housed at the zoo, it appears that Gusky suffered alone in captivity for over twenty years.

In July 1923, a new three-year-old female Asian elephant was brought to the zoo. The occasion prompted a Pittsburgh Post editorial chiding officials to make good on the obvious needed improvements to the facility:

Gusky, the big elephant, has stood long enough tethered to a single spot of cement floor to establish a strong indictment against Pa Pitt as an animal keeper. Grownups can look back to their childhood when they saw Gusky tied to the same stake. The proper enclosure to allow her greater freedom and an opportunity to exhibit more as she chose, should have been provided long ago. Nothing tied to a stake can remain interesting for any length of time. The young elephant to cross the sea to live at the zoo should not be permitted to enter a career such as Gusky has endured.

One paper speculated that Gusky was now a “motherly old elephant” who could take the new baby - named Gloria Swanson for the glamorous 1920s Hollywood movie star - “in charge, teaching it the etiquette of zoo life.”

|

| A new elephant arrives at the Highland Park Zoo, to be named Gloria. Pittsburgh Post, 11 July 1923 |

It wouldn't be surprising if decades of solitary captivity had impaired Gusky’s ability to bond with other elephants, but newspapers reported that she and Gloria “would stand for hours with their heads together and their trunks interlocked in demonstration of their close affection.” Perhaps Gusky finally found comfort in matriarchal love with little Gloria.

But it was not to last. Three years later on 17 May 1926, the zoo announced that Gusky had died in the night. She had been suffering for nearly a week after paralysis of the trunk robbed her of the ability to take in nourishment. While keepers hand-fed her as best they could, she was too enfeebled to rally. She finally fell over “with a terrifying cry” and the end came in a matter of hours.

Gloria was reported to be “almost unmanageable” when Gusky fell, for she “trumpeted plaintively and tried desperately to reach her old companion." Gloria then exhibited decreased appetite and agitation, tossing straw and bedding and straining at her chain. The zoo staff thought these were signs of grief -- and they were probably right given what we’ve since learned about how elephants mourn and honor their dead. The most poignant commentary came from a headline in the New York World: “Gusky lies in 12-foot grave, Gloria grieves alone.”

Gloria wasn’t the only one who grieved, as local papers devoted considerable space to telling Gusky’s story. But the press never could get things right about Gusky, even at the end. To be fair, there was no easy fact-checking access to digital archives in 1926. But the inconsistencies in reporting Gusky’s age are nonetheless startling. Locally, the Press said she was 85 while the Post and Gazette-Times claimed she was 65 years old. The story was subsequently picked up by wire services and newspapers from Miami to Missouri split the difference, reporting that Gusky was 75 years old. The Press even claimed that Gusky had been around in “Civil War times” and was subsequently presented to the Schenley Zoo by Esther Gusky in 1888!

If Gusky was 5 years old when she came to the Schenley Zoo in 1890, she would have been about 40 years of age when she died in 1926. That is entirely consistent with the life span of an Asian elephant in captivity today -- and surprisingly so back then, when conditions were much worse for captives. Gusky truly was the G.O.A.T., with fierce survival instincts and staying power.

Some interesting tidbits emerged in the newspapers obituaries. A fellow named James O’Neele was identified as Gusky’s keeper “ever since she became city property.” There were also mentions of a “bewildered” Gusky being brought into the Gusky department store as an advertising stunt in her earliest days. A Press anecdote recounted her strength and likely frustration with captivity: “Gusky got loose from her chain several years ago, pulled the posts of the strong iron fence around her big stall up out of the concrete and twisted heavy iron pipe rails into knots.” And while never renowned for purposeful exertions like Punchy, Gusky was apparently called upon at least once as a laboring beast: “Another time a heavy load of lumber, horse-drawn, stuck in the mud on its way to the zoo. Gusky was led out to the load, put her big head against the rear of the load and pushed it out apparently without effort.”

Unlike her predecessors at the turn of the century, Gusky’s remains were not turned over to the Carnegie Museum. Her five-ton carcass was moved by workers from the John Eichleay Jr. Company (an engineering company still in existence today) onto a truck trailer. “Burying an elephant is largely a matter of mechanics,” Press readers were told. “Chains and cables, ropes, pulleys and a powerful gasoline motor were used to pull and tug and twist and turn the massive weight across the floor, through two doors and out to the trailer. Moving a building would have been a simple matter compared with this task.” Perhaps this last bit came straight from the source, for in fact the Eichleay Company had moved its fair share of buildings.

It took workers two days to dig the 12 x 12 foot grave behind the zoo, somewhere off Stanton Avenue on a wooded hillside near Carnegie Lake and an old bandstand, overlooking Washington Boulevard. “Some future generation may unearth her bones and startle the world with the information that elephants once roamed western Pennyslvania,” joked the Press. “This is possible unless Gusky’s human friends mark her last resting place with a permanent tablet, that will pass her history down to their descendants.”

So far as I know, there is no such tablet marking Gusky’s grave in Highland Park. Save for reminiscences like this one, she’s been long forgotten, or conflated in memory with the many elephants that came after her at the Pittsburgh Zoo.

But for 35 years, Gusky was a constant presence for

generations of Pittsburgh kids who fed her peanuts (or straw hats) and rode on

her back. Her life bridged the old-fashioned gay ‘90s with the early decades of

a new century shaped by the Great War and social change; her life ended in the

raucous 1920s. She outlived Edward Manning Bigelow, Esther Gusky and her brother Levi DeWolf, and all of her companions save little Gloria.

Gusky passed in Pittsburgh’s collective consciousness from a diminutive “baby” to a wise old maternal elephant. Pittsburgh parents remembered her from their childhoods, and they took their own kids to visit her.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 7 January 1903 |

It should be a cautionary lesson to us that Gusky’s life was spent in a captivity so lonely and traumatizing that equally abiding collective memory centered her

self-comforting repetitive behaviors.

Modern debates about approaches to elephant conservation are powerful and passionate. Gusky's life serves as a reminder to always do better, and to be intentionally kinder to the animals whose lives we are stewards of.

|

| Gusky, c. 1886 -1926 Pittsburgh Press, 17 May 1926 |

_______________________________________________________________

Thanks to Pittsburgh City Archives for sleuthing the Gusky proclamation, and to Paul Simon for writing At the Zoo.

For more information about elephant rescue and conservation efforts, check out these charities.