Then Susanna cried out with a loud voice, and the two elders shouted against her. ...And when the elders told their tale..the assembly believed them, because they were elders of the people and judges... -Daniel 13

|

| Paolo Veronese, Susanna and the Elders, 1585-88 |

My mother chose to name me Susan because back then, it was a pretty, popular name. Saddled with the given name of Agnes, she wanted something less old-fashioned for her daughter. There was a saint attached to the name, too, which gave it that all-important Catholic legitimacy.

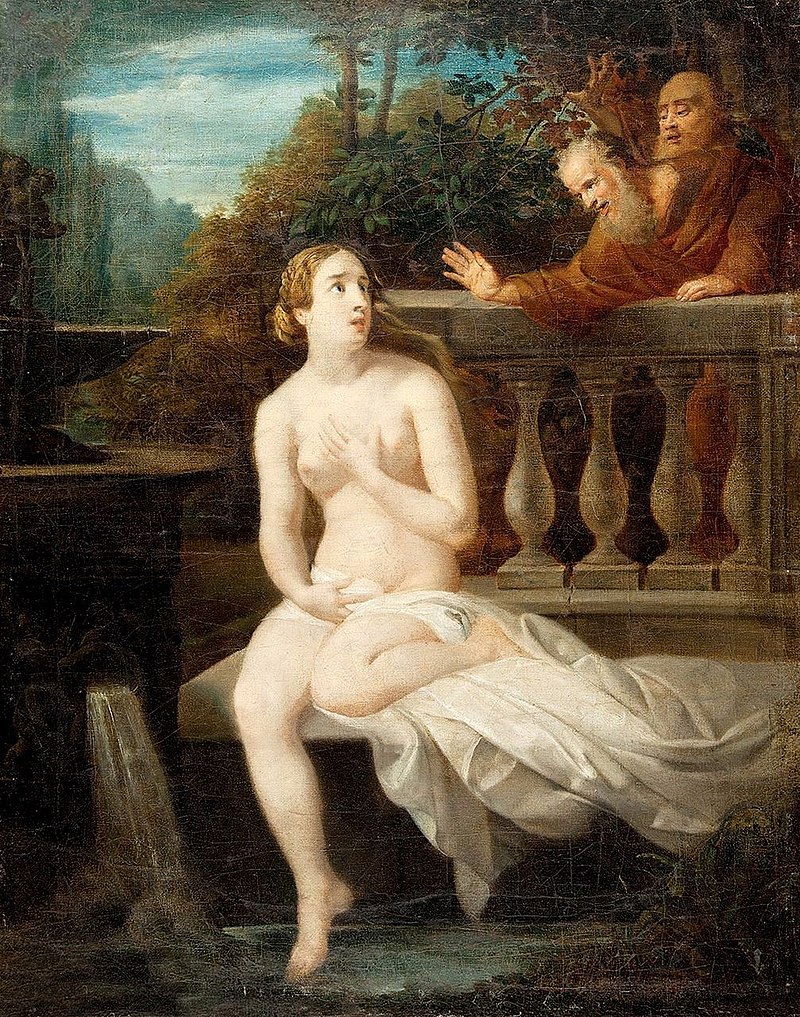

|

| Artemisia Gentileschi, 1610 |

I was 6.

Well, you can imagine. I didn't understand most of what I read. I came away with an icky sense that the Biblical Susanna had done something shameful and got punished for it. I had questions, but no one to answer them, so I was left with a lingering sense of embarrassment about the whole thing. I even briefly tried to obscure the saintly connection by spelling my name Susann when I was in junior high (yeah, that was also as edgy as I got).

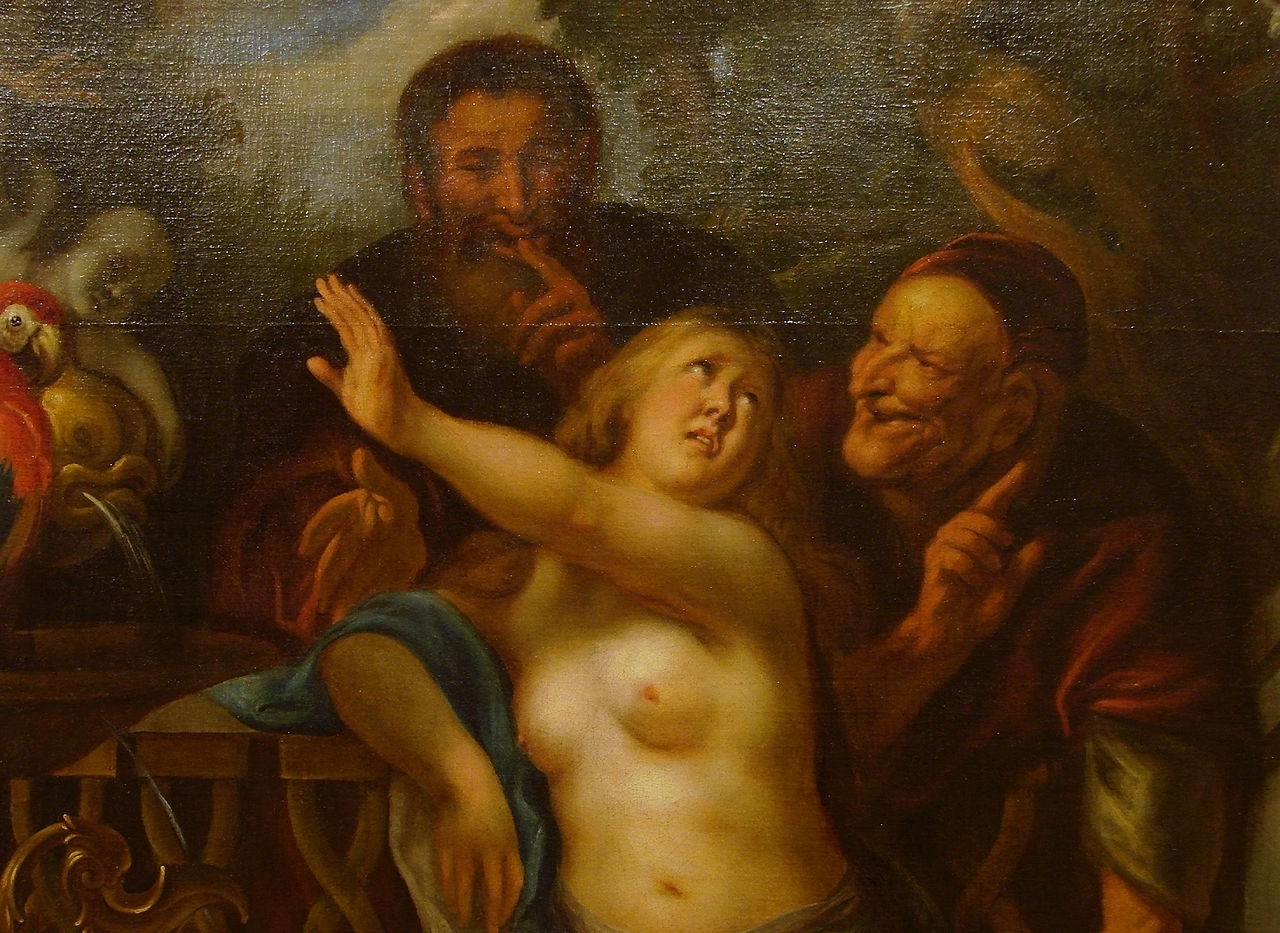

|

| Flemish school, 17th century |

Routinely. That sounds weird, but in the late 80s and 90s when I was working, asking these questions wasn't as common as it is (I hope) today.

And because I asked them questions no one else had ever raised, so, so, so many people told me things they'd never told anyone.

|

| Rafał Hadziewicz, 19th century |

If you’re reading this thinking I’m writing my #metoo, nope, that’s not what this is. I’ve personally endured nothing more than the routine catcalls and fending-off of boorish advances (Yes, routine. All part of being a woman). I was incredibly lucky.

That’s all it was, luck.

|

| Il Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto Betti detto), fresco, 1492-94 |

Certainly those courtesies, those privileges, are not extended to everyone who has such a story. Maybe you disagree, or maybe you think you don’t know anyone who’s had such experiences. You’re dead wrong about that. Everyone has their stories. You just haven’t been told them.

You're not entitled to them. Some people will never tell their stories.

But if they choose to speak, shut up and listen.

I haven’t returned to my former profession since my first child was born. I wasn’t burned out, but I knew my limits, and knew I couldn’t be the type of parent I wanted to be and the type of therapist I wanted to be at the same time. Parenthood won.

And besides, I’d long since come to understand what really happened to Susanna.

She told her story.

She was lucky. At the end of the day, she was listened to, and believed.

But it came at cost. Because once you tell your story, you have to ask yourself: now, what? And that’s the question we’re facing as a nation: what do we do with our Susanna’s story? With our Susannas? We’re at a disadvantage here. We have no Daniel to guide us.

|

| Gerrit van Honthorst, early 17th century |

Defined particularly by what the old men said had happened.

|

| Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, 1751 |

I have heard countless painful stories. Mostly from women, but some from men. I made a place deep inside where I laid them gently to rest. It is a safe inner room, protected by silver tears that have dried hard into knives to protect against future pain, so I could raise my daughter with the necessary anxiety to live in a predatory world, and raise my son to respect and protect.

I don’t want there to be new stories.

But of course, there will be.

Susanna surely was with Dr. Ford, with all who tell their tales. And I couldn’t have asked for a better patron saint.