|

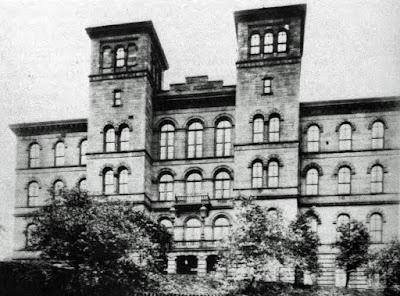

| Pittsburgh's Penn Station, circa 1904. Library of Congress collection. |

The short answer is that the fortification looming above the station was Pittsburgh’s first high school.

The long answer?

Settle in…

In the beginning, there were rats…

There was once considerable apathy and even outright opposition to the idea of a public high school in Pittsburgh. The Free Schools Law of 1834 divided Pennsylvania into school districts, with residents in each district voting about whether they wanted local schools subsidized in part by the state. The first public high school was established in Philadelphia in 1836, but it took another twenty years for Pittsburgh to embrace public high school education. The School Code of 1854 allowed district school boards to set teacher salaries, define grade levels and admission parameters, select subjects (although the state mandated orthography (spelling), reading, writing, grammar, and geography be taught in every school), and choose textbooks.

With those guidelines established -- and despite continuing citizen complaints about school taxes and teacher salaries -- Pittsburgh opened its first high school on 26 September 1855.

|

| Illustration from Fleming's My High School Days |

|

| Pittsburgh Gazette, 26 September 1855 |

Pittsburgh’s experiment in public high school education started with a student enrollment of 115. Within three days, a student had already dropped out, and only three of those 115 students eventually graduated.

The first diploma ever handed out in a Pittsburgh public school in 1859 was actually to a young lady, Miss Hephzibah Wilkins (later Mrs. Joseph S. Hamilton). Heppie Wilkins returned some years later as school preceptress, a female administrator who attended to the "special" needs of female students. She was promoted to teaching English, and was the school’s only female teacher from 1866-69. Her annual salary rose from $625 to $800 over the three years that she taught, until she was required to leave her position upon getting married.

|

| Diploma issued to Heppie Wilkins, a niece of prominent Pittsburgher Judge William Wilkins From Pittsburgh Central High School Alumni Directory, 1859-1905 |

The Civil War interrupted public high school education in Pittsburgh for many young people for the better part of a decade. Eventually enrollment increased, and conditions improved when the school moved in 1868 to four floors of the five-story old Bank of Commerce Building at Wood and Sixth.

|

| Illustration from Fleming's My High School Days |

Then again, “improvement” was relative, given conditions at the first Smithfield school. George T. Fleming, a 19th century raconteur and writer who penned multiple memoirs and curiously curated histories of Pittsburgh, was a student at both the Smithfield rooms and Commerce Building. His memories of Smithfield classroom conditions had not dimmed fifty years later when he recounted his experiences in various narratives. Fleming’s vivid descriptions still entertain: Latin recitations shouted above the din of ceaseless wagon traffic on cobblestone streets, punctuated by tunes from an itinerant accordion player with a limited repertoire, and accompanied by the bellowing of an auctioneer from the floor below. Fleming and his fellow students fortunately had other distractions:

It was always a blessed relief when one or more of the predatory rats that infested the building, or even some quick-actioned mice, emboldened by hunger, would emerge from one of the numerous crannies in the old rooms, and begin to forage for the leftovers from lunch hour that had dropped on the floor. This sort of invasion invariably led to action. Any missile in reach –a piece of chalk, a small lump of coal, an ink well or its cover--perhaps, a surreptitious bone, would be hurled….at those miscreants by other miscreants. Perhaps a crust hardened by age was the only available ammunition, but the first opportunity and the nearest sharp shooter to the enemy got in his work quickly, regardless of the demerits that were sure to come and increase someone’s already plethoric list.Compared with the first school site on Smithfield, the Commerce Building had the advantage of “larger, cleaner rooms…better light and ventilation” (and, presumably, fewer rodents). It was quieter, too: no accordion players or auctioneers, plus Wood Street was paved with wooden blocks. The new building had five floors with a long, steep staircase built to accommodate students; steam heat; and a large chapel. Enrollment did fluctuate as students came and went, but the Commerce Building school was soon overcrowded. More than one class was conducted at the same time in the same room, and even the chapel was called into usage as a classroom.

By the 1870s, the growing city of Pittsburgh needed a real high school.

_________________________________________________

Pittsburgh’s Central High School, The People's College….

It was precisely because the city was growing that land in the Hill District became available to the Central Board of Education. |

| Pittsburgh Press sketch from 1890. |

The two Bedford basins remained critical for the city’s water supply needs until the 1890s, when they were converted into city parkland. But the Central Board of Education called dibs on the unused property for a new high school. City Council donated land high on the bluff overlooking Union (aka Penn Station) and Bigelow Boulevard, at the corner of Fullerton (now Fulton) and Bedford Avenue.

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School Illustration from Fleming's My High School Days, edited |

And so it was that the cornerstone for the first purposely-built high school in Pittsburgh was laid during a gala ceremony on 30 September 1869. This new building was a huge deal. Pittsburgh celebrated with a parade of 4,000 students from all of the city’s various elementary schools marching in grand procession, accompanied by various dignitaries, policemen, and brass bands. The schools were designated with flags and silk banners, and the littlest girls carried floral wreaths or bouquets as they processed through the streets. They strolled from Penn Avenue and Fifth Street downtown, up to the site on the Hill. A crowd of 10,000 spectators followed the parade beneath an evergreen arch, then gathered around a stage set up over the foundations of the new building.

That stage supported the many speakers of the day, plus six brand new Estey pump organs to accompany the musical selections. (Six pump organs!) Speeches were made, prayers were invoked, songs were sung, music played, poems read, and dignitaries engaged in an orgy of self-congratulation. Finally, a time capsule containing a copper box containing Central Board of Education material, cultural, and educational memorabilia was ceremoniously dedicated and lowered into the cement cornerstone with three raps of a mallet by Principal Philotus Dean. The local papers printed detailed accounts of the day, including many of the speeches, and dubbed the school on the hill “The People’s College.”

|

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette montage, 9 October 1920 |

|

| Contents of Pittsburgh Central Cornerstone Time Capsule |

The twin-towered stone and brick building was designed by the Pittsburgh architectural firm of Barr and Moser and constructed by local contractors. It was completed in 1871 at a cost of $200,000. It was a building that filled Pittsburgh with pride, with its 30 classrooms for 600 students, lecture hall, proscenium stage and 1000 seat auditorium, science labs and library.

| ||

| Pittsburgh Central High School above the second Penn Station, circa 1877-1898 Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation Collection Photographs Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

|

| 1889 image from Pittsburgh and Allegheny Illustrated Review by John W. Leonard |

Some interior photographs taken decades later, circa 1914-17, show the stage and a later cafeteria addition.

|

| Pittsburgh Central stage setting for student performance of the comedy Einer Muss Heiraten, 1914 Edward J. Shourek Photograph Collection Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School Cafeteria, 1917 Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, 1880-1982 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School Kitchen, 1916, either for student practice or the cafeteria Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, 1880-1982 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

Admission to Central was based on a passing grade of 65% or better on entrance exams in maths, grammar and spelling, geography and US history.

Students could pursue a one-year Commercial or business-related degree; a two-year Normal Department program designed “to prepare teachers for our city schools”; or an Academic program which followed a traditional liberal arts and sciences curriculum.

Central's first year’s enrollment totaled 436 students, divided across programs as follows: Commercial, 57; Normal, 94; and 285 in Academic. A typical school day lasted from 8:45 AM until 2:15 PM, with a twenty minute recess.

George Fleming wrote an entire book in 1904 looking back at Central's early years, which he titled My High School Days. He included long biographical sketches of teachers he was privileged to study under, as well as this copy of Central's schedule of classes for the 1869-70 school year.

|

| B.C. Jillson, MD, PhD Fourth Principal Of Central High School, 1871-1880 |

Members of the Board and many Pittsburgh citizens complained that the public high school was "an expensive luxury." Faced with pressure in 1874 from the Board to promote a two year degree to improve attrition and secure a better economic return on the city’s educational investment, Principal Benjamin Cutler Jillson resisted. He testified that Central was more than holding its own, and needn't dumb down its academics. "Everything of value costs money and our high school is no exception,” he wrote in a report reprinted in the local papers, along with charts and graphs showing longitudinal Pittsburgh high school attendance, attrition statistics, and favorable comparisons with Philadelphia and Chicago high schools.

The Board continued to exercise its due diligence oversight of the school. But as Pittsburgh’s population grew and higher education became more valued in society, Central's enrollment and attrition issues stabilized.

_________________________________________

Central’s students and teachers…

| |

| Pittsburgh Central High classes in 1913 Edward J. Shourek Photograph Collection, University of Pittsburgh |

Central had a diverse student body...or as diverse as cultural and economic conditions in Pittsburgh allowed.

Which is to say, the student body wasn't particularly racially diverse.

Central did provide the first desegregated educational options for the city’s black population, whose students previously had no choice but to attend “colored” or “separate” schools. The Pittsburgh School Board funded a separate school for black students in 1838, but that school did not have a dedicated space until 1867 when the Board purchased lots on Miller Street in The Hill. Enrollment was never robust, in part because Pittsburgh’s black community was so geographically dispersed in pockets across various city neighborhoods that getting to a centralized school on The Hill was a challenge. During the Reconstruction era Pittsburgh joined in the national debate about integrating its public school systems, particularly significant since the separate Miller Street School House was not far from Central. Citing poor enrollment and expense, there was Board opposition to keeping it open.

Integration, then as now, was a controversial issue -- and not merely for the predictably racist reasons. An 1872 newspaper account summarized the fractious debate at a Board meeting at which ending “separate” schools like Miller Street was discussed:

A number of members held that if the colored children were admitted into the ward schools it would create great dissatisfaction among the white residents of the several wards, and that the majority of the white scholars now attending the schools would be withdrawn. It was also held that the great majority of the colored people, nineteen out of twenty, were satisfied with the present school system, and did not desire to send their children to the ward schools, as it would be unpleasant both to their children and the white scholars. Others held that the Fourteenth amendment gave the colored people all the rights of citizenship, and that under this amendment they could claim the privilege of sending their children to the public schools.

|

| Dr. George G. Turfley with one of his grandchildren Dorsey-Turfley Family Photographs, 1880-1987 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

There were three black students in Central’s 1872 class. Dr. George G. Turfley, who had previously attended the city's “separate schools”, was one of Central’s first black graduates in 1876. He became one of Allegheny County's first registered black doctors, with practices in Arthursville on the Hill and elsewhere.

Black students who wanted to continue schooling into their teen years had no choice but to attend Central after 1875, but Central's enrollment would always be dominated by white students.

|

| Central class photo from 1914. Shared by Bryan Henn, whose 2x great-aunt Clara Louisa Hilf (1900-18) is pictured next to last row, 4th from left. |

|

| Central High Students from 1916 Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, 1880-1982 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

Central lived up to its name as the city's "central" high school by drawing students from all residential areas of the city at that time, including neighborhoods we think of today as Oakland, The Hill, Shadyside and East Liberty, Lawrenceville, and even the four boroughs that make up today's Southside.

A survey of some of the 87 graduates of 1880 revealed that the class included fourteen Presbyterians, nine Methodists, three Baptists, two Catholics, one Lutheran, one Jew, and "...two or three (boys) are nothing, and one is anything to suit the circumstances." Irish and German girls from the upper working and middle classes attended the school in significant numbers. The “Normal School” program was particularly popular, for it provided girls with the era’s approved educational background to become teachers.

Principals were referred to as Deans and college-degreed male teachers were known as Professors.

There were female teachers as well, including Pulitzer Prize-winning author Willa Cather. After graduating from the University of Nebraska in 1896, the 22 year old Cather’s first job was as an editor for a new women’s magazine called The Home Monthly based in Shadyside. That job only lasted a year, at which point she became a writer for the evening newspaper The Pittsburgh Leader. Cather presumably found that newspaper work wasn’t conducive to creative writing. She became an instructor at Central in 1901, where she taught Latin, English and algebra until transferring to another local school in 1903. One of Cather's former Central students, John O'Connor Jr., went on to become Assistant Director of Fine Arts at Carnegie Institute. He was interviewed by the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph at the time of Cather's death inn 1945:

A survey of some of the 87 graduates of 1880 revealed that the class included fourteen Presbyterians, nine Methodists, three Baptists, two Catholics, one Lutheran, one Jew, and "...two or three (boys) are nothing, and one is anything to suit the circumstances." Irish and German girls from the upper working and middle classes attended the school in significant numbers. The “Normal School” program was particularly popular, for it provided girls with the era’s approved educational background to become teachers.

|

| Willa Cather during her Pittsburgh years Willa Cather Foundation |

There were female teachers as well, including Pulitzer Prize-winning author Willa Cather. After graduating from the University of Nebraska in 1896, the 22 year old Cather’s first job was as an editor for a new women’s magazine called The Home Monthly based in Shadyside. That job only lasted a year, at which point she became a writer for the evening newspaper The Pittsburgh Leader. Cather presumably found that newspaper work wasn’t conducive to creative writing. She became an instructor at Central in 1901, where she taught Latin, English and algebra until transferring to another local school in 1903. One of Cather's former Central students, John O'Connor Jr., went on to become Assistant Director of Fine Arts at Carnegie Institute. He was interviewed by the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph at the time of Cather's death inn 1945:

He still cherishes a yellowed composition paper of his on which she marked "Good." She was well-liked by the pupils, he said, who found inspiration in the breezy, western way she had with people. She dressed plainly in tailored clothes, he said, and always wore her hair parted Madonna-like in the middle.

Two of the short stories Cather wrote during this time were psychological studies that featured Central High School: “The Professor’s Commencement” and “Paul’s Case.” The latter was likely inspired by 1902 sensational newspaper accounts about two Pittsburgh teens who absconded to Chicago with money they’d stolen from a local real estate office. Cather mixed such source material with a teacher’s perspective on reaching problem students; the social claustrophobia and disappointments of academic life; and descriptions of Central’s surrounding neighborhood in all its brute physicality.

|

| Central High on the hill, 1907, looking over a flooded Allegheny River F. Theodore Wagner, Photographs, ca. 1903-1947 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

These stories also made manifest Cather’s dichotomous vision of Pittsburgh culture, which she described in an 1897 Nebraska State Journal article: "Now all Pittsburgh is divided into two parts. Presbyteria and Bohemia, and the former is much the larger and more influential kingdom of the two."

In “The Professor’s Commencement” Cather’s elderly English Literature teacher had only meant to teach for a short time but found “….the desire had come upon him to bring some message of repose and peace to the youth of this work-drive, joyless people, to cry the name of beauty so loud that the road of the mills could not drown it.” And yet, thirty years later, Cather's fictional professor found himself plagued with regret and unfulfilled dreams. He felt as if “All those hundreds of thirsty young lives had drunk him dry.”

At his retirement dinner, the Professor looked about the room:

….picking out the faces of his colleagues here and there, souls that had toiled and wrought and thought with him, that simple, unworldly sect of people he loved. They were still discussing the difficulties of the third conjugation, as they had done there for twenty years. They were cases of arrested development, most of them. Always in contact with immature minds, they had kept the simplicity and many of the callow enthusiasms of youth. Those facts and formulae which interest the rest of the world for but a few years at most, were still the vital facts of life for them. They believed quite sincerely in the supreme importance of quadratic equations, and the rule for the special verbs that govern the dative was a part of their decalogue…He looked about at his comrades and wondered what they had done with their lives. Doubtless they had deceived themselves as he had done. With youth always about them, they had believed themselves of it. Like the monk in the legend they had wandered a little way into the wood to hear the bird’s song—the magical song of youth so engrossing and so treacherous, and they had come back to their cloister to find themselves old men….

Central High faculty, 1880-90s

Cather’s Professor lived in the neighborhood near Central, and through his disenchanted eyes we see the school dominating the cityscape, set high as a fortress above the vast manufacturing wasteland below:

The High School commanded the heart of the city, which was like that of any other manufacturing town—a scene of bleakness and naked ugliness and of that remorseless desolation which follows upon the fiercest lust of man. The beautiful valley, where long ago two limpid rivers met at the foot of wooded heights, had become a scorched and blackened waste. The river banks were lined with bellowing mills which broke the silence of the night with periodic crashed of sound, filled the valley with heavy carboniferous smoke, and sent the chilled products of their red forges to all parts of the known world—to fashion railways in Siberia, bridges in Australia, and to tear the virgin soil of Africa. To the west, across the river, rose the steep bluffs, faintly etched through the brown smoke, rising five hundred feet, almost as sheer as a precipice, traversed by cranes and inclines and checkered by winding yellow paths like sheep trails which lead to the wretched habitations clinging to the face of the cliff, the lairs of the vicious and the poor, miserable rodents of civilization. In the middle of the stream, among the tugs and barges, were the dredging boats, hoisting muck and filth from the clogged channel. It was difficult to believe that this was shining river which tumbles down the steep hills of the lumbering district, odorous of wet spruce logs and echoing the ring of axes and the song of the raftsmen, come to this black ugliness at last, with not one throb of its woodland passion and bright vehemence left.

Cather’s descriptions of teaching are not idealized. Faced with an intractable student in Paul’s Case, her fictional Central faculty found itself

Cather’s own teaching experiences and attitudes are surely reflected in these stories, though dramatically augmented. Perhaps having created a cautionary tale, and wary of squandering her own vitality as her fictional Professor

had done, Willa Cather left teaching and Pittsburgh in 1906.….in despair, and his drawing teacher voiced the feeling of them all when he declared there was something about the boy which none of them understood…His teachers left the building dissatisfied and unhappy; humiliated to have felt so vindictive toward a mere boy, to have uttered this feeling in cutting terms and to have set each other on, as it were, in the gruesome game of intemperate reproach.

Cather’s stories notwithstanding, life at Central wasn’t all drear and drudgery. The newspapers dutifully reported on the Academic program’s college-bound scholars; Central’s many athletic teams representing football, baseball, hockey, and girl's basketball; its orchestral, choral and stage productions; and the school’s literary and honor societies. There were clubs, too, for photography and naturalists. There was even an unnamed tech nerd group in the 1880s, described as "...a group of technology enthusiasts doing wood and metal work such as laboratory apparatus, minor repairs, care of the electric lighting, and the installation of a useful telephone system which has saved the school a goodly amount of money."

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School Band, 1914 Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, 1880-1982 Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

| |

| 1913 Central trophy case Edward J. Shourek Photograph Collection, Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

|

| Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 21 March 1902 |

Central High School students professed a strong esprit de corps. No doubt the official "yells" helped consolidate school spirit. From 1889:

Rickety-smack! The Red and the Black!

Rickety-Smack! The Red and the Black!

High School! Keep Cool!

Sis! Boom! Rah!

And this, from 1896:

Hi! Yi! Yi! Sis! Rah! Boom!

Pittsburgh High School! Give us room!

Boom ter at um! Out of sight!

Pittsburgh High School! We're all right!

There was also at least one Central school song, in four-part harmony:

And of course, there were hi-jinks. Students got in trouble and were disciplined for the usual creative adolescent reasons. Take, for instance, Hartley Phelps. In 1890, Mr. Phelps received a two week suspension for roasting the faculty during an essay he presented at the school’s Dean Literary Society. (Note to Hartley: don’t count on your Daddy being a School Board member to keep you out of trouble. Publicly mocking the principal’s bald head isn’t exactly endearing to said principal. Plus, your Daddy Thomas was a former tax collector, so maybe not the most popular guy in town).

But fear not! There was a Team Hartley, 1890s-style. The next day, all the boys in his class wore black crepe mourning armbands, and the girls wore "black court-plaster on their cheeks" in a show of solidarity. More suspensions were handed out, parents groused about faculty who couldn't take a joke, and Pittsburgh papers had fun reporting about Hartley-Gate.

Hartley Phelps apparently liked seeing his name in newsprint, and was too clever with words for his own good. He went on to a career as a Pittsburgh newspaperman, specializing in detailed feature stories about the city's history. He was the lead historical author of a book that historical dilettantes like me turn to quite often: Palmer's Pictorial Pittsburgh and Prominent Pittsburghers Past and Present, which contains profiles of this city's VIPs (no mocking of bald heads allowed). Hartley never married, and died at the age of 44 in 1915.

Photo documentation of other high school hi-jinks is sadly lacking in details. Did the fellows below, identified as "Midge, Boob, and Shrimp", ever get busted for casually posing on the school's rooftop ventilators in 1914? Perhaps we're looking at Class of 1914 Senior Pranks.

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School rooftop shenanigans, 1914 Edward J. Shourek Photograph Collection Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School rooftop shenanigans, 1914 Edward J. Shourek Photograph Collection Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

Central classes regularly met for reunions, and published directories so alumni could stay in touch.

|

| Class of 1880's 25th reunion, Steamboat Liberty on the Monongahela River |

Clearly cherished memories were made, and lasting relationships were forged.

______________________________________

|

| Franklin School, renovated 1890 Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

The Commercial program expanded to two years. It was particularly popular for those seeking real-world business and trade skills. By 1893 the Commercial program had been spun off and moved to the newly-renovated Franklin School at Franklin and Logan Streets in the Hill. It was favorably profiled in the paper, with profiles about faculty and students.

|

| From The Pittsburgh Press, 5 March 1893 |

|

| Pittsburgh Press profile of Central faculty head. 17 September 1898 |

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School in 1915 Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh |

Central stopped operating as a traditional high school entirely when Schenley High School in Oakland opened in 1916. At that point Central became the home of the two-year Short Course Business High School, which was quite successful during its 15 year existence.

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School in 1921 Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh |

By 1929, the business program at “old Central” had an annual enrollment of nearly 1000, with some 40 faculty under the supervision of Principal Louis B. Austin.

By 1929, the business program at “old Central” had an annual enrollment of nearly 1000, with some 40 faculty under the supervision of Principal Louis B. Austin.But the 1870s-era building was by this point quite outdated. In 1929, all the local papers reported on some new classrooms going up next door to Central:

|

| Pittsburgh Press, 16 September 1928 |

|

| Pittsburgh Central High School in 1930, with new Connelley complex behind Pittsburgh City Photographer Collection, University of Pittsburgh |

|

| This survey done in late 1920s by Pittsburgh School Board shows relationship of new and old facilities. Used with permission, courtesy of Pittsburgh City Archives, City of Pittsburgh |

|

| PA Dept. of Labor & Industry Commissioner, City Councilman, technical & industrial education advocate. |

Principal Austin died in 1929. His position was taken by David Daniel Lessenberry. But even with a change in leadership, the writing was on the blackboard for old Central High and the programs it sheltered.

By 1933 a completely new school drew attention at the corner of Bedford and Fullerton: the state-of-the-art Connelley Vocational High. Central's secretarial and clerical programs had expanded and shifted to the new facility.

Old Central High School was used over the next ten years to house Pittsburgh offices for the National Youth Administration Student Work (aka Work Project) Programs. These were New Deal initiatives to provide vocational training and employment for young people in construction, manufacturing, clerical and service fields.

Central was finally demolished in 1946. That was the same year that its 1870s-era contemporary, the long-abandoned Old City Hall Building on Smithfield Street, was destroyed.

|

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 1946 |

|

| Central stones? St Anthony's Chapel from Historic Pittsburgh Image Collection |

|

| 10-22-95 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette |

Wherever its physical remnants may be, Pittsburgh Central has faded from living memory. The last generation of some 5000 students who walked the halls of The People’s College having mostly passed on.

_____________________________

Selected Bibliography and Further ReadingArchives of Pittsburgh newspapers. Please contact me for specific citations.Bintrim, Timothy W. and Mark J. Madigan. “From Larceny to Suicide: The Denny Case and ‘Paul’s Case.’“ In Joseph R. Urgo and Merrill Maguire Skaggs (Editors). Violence, the Arts, and Willa Cather. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. 2007.Class of 1880 Pittsburgh Central Catholic Academical Department. Class Book 1880. Murdoch, Kerr & Co.: Pittsburgh. 1905Fleming, George T. My High School Days. Pittsburgh, PA: Wm. G. Johnston & Co. 1904.Fleming, George T. “The Old Central High School.” The Pittsburgh Gazette. 13 June 1920.Hadley, S. Trevor. “Central High School: Pittsburgh’s First.” Pittsburgh History, Volume 73, Number 2, Summer 1990.Hamilton, Heppie Wilkins. The old Central High School (P.C.H.S.): reminiscences of the class of 1859. Pittsburgh, PA: Dean Pupils Assoc. 1915.Oresick, Peter (Editor). The Pittsburgh Stories of Willa Cather. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University Press. 2016Snyder, Thomas D. (Editor). 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait. Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. 1993Sughrue, Patty. The Historic Miller School. In Memories from Miller. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. 2005.“The People’s College.” The Pittsburgh Commercial. 1 October 1969.Thompson, Leonard. “The First Hundred Years.” The Pittsburgh Press. 21 August, 1955.