Edward Alexander Montooth was a big deal back in his day. He also had a pretty nifty house in Pittsburgh's Hill District.

Major Montooth and Old Pittsburgh

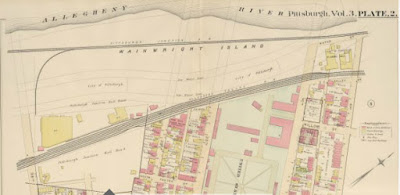

Edward Alexander Montooth was born 18 September 1837 in the third ward of Pittsburgh, which was an area defined by Eighth Avenue to the north, Diamond Street (now Forbes Avenue) to the south, Market Street to the west and Grant Street to the east. His father was a respected downtown merchant. Edward was the eldest of several children, four of whom survived to adulthood. At some point in the late 1870s the four unmarried Montooth siblings and their widowed father moved from downtown to the Hill District, which at that time was made up of a mixture of large houses like the one they lived in (above), along with smaller row houses. The Montooth home is in the center of the above photo (the wings were added later). Plat maps of the era indicate that there was a structure on this lot in the 1870s, so their home may date to that time.The house was across the street from Pittsburgh Central High School, in the area where Connelly Skill Learning Center is located today.

|

| From "Flem's" Views of Old Pittsburgh |

Edward Montooth studied law and was admitted to the bar in December 1861, but the American Civil War inconveniently interfered with his career plans. “He forsook a fast-growing practice” and enlisted in the Union Army, enrolling as First Lieutenant in Company A, 155th Pennsylvania Infantry on 23 August 1862. Rising through the ranks over the years, Montooth distinguished himself on the fields of Antietam, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, and was brevetted major for meritorious conduct at Gettysburg. He was mustered out on 2 June 1865 and resumed his interrupted law practice in Pittsburgh. For the next 30+ years, he partnered with his brother Charles and fellow Pittsburgh Civil War veteran J.T. Buchanan at the firm of Montooth Bros. and Buchanan.

|

| Pittsburgh Daily Post, 19 December 1889 |

It's no exaggeration to describe Edward Montooth as a pillar of post-Civil War Pittsburgh society. He served as Allegheny County District Attorney from 1874-77, and had unsuccessful runs for Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor in 1886 and Governor in 1890. He was much esteemed for his military background and was active in the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), serving as Grand Marshall for local veteran parades. He was such a recognized and venerated Pittsburgh character that a life-sized photograph of him was placed in a gallery window in 1884 to show off the “perfect likeness” reproductive quality of a local photography studio’s work.

Montooth was so well-respected in his profession that an 1887 Pittsburgh Bulletin profile proclaimed:

….he has always possessed the confidence of the people in his ability as a lawyer, as shown by his having been concerned in every prominent trial –particularly for homicide—for the past seventeen years. In nearly every case he defended the accused, and only one of his clients was ever hanged….

The Bulletin also glowingly described Montooth’s non-professional attributes:

|

| From Palmer's Pictorial Pittsburgh, 1905 |

|

Illustration from Homestead by Arthur G. Burgoyne, 1893

|

|

| Maj. E.A. Montooth Fort Frick by Myron R. Stowell, 1893 |

Meridians of manhood, larger-than-life reputations, and popular “An American Abroad” lectures don’t put off death, however. After suffering a progressive “affection of the liver” of some four years, Major E. A. Montooth died 9 February 1898.

He was buried in the family plot in Allegheny Cemetery (sec 19 lot 78). The Pittsburgh Legal Journal memorialized his

career and character, echoing praise heaped upon him during his lifetime:

After he retired from the District Attorney’s office, he at once assumed a leading position in our profession as a natural leader, especially in criminal justice. For many years he was engaged in nearly every cause before the court and jury. He had a very valuable practice in homicide cases. As an advocate, had no superior and few equals. His thought was of the man as much as his cause. His candor and fairness won him the confidence and respect of the best class of persons. His conduct as counsel was eminently open and fair. He had no secrets from his associates. As an adversary he was formidable; his candor and fairness was really strength. Major Montooth had many minor accomplishments not generally known to the public. He was a man of artistic tastes. He loved art, and had purchased whilst abroad many things that suited his taste. He had skill as an artist. He held the brush in a modest way and portrayed his tastes. He was a musician and enjoyed the harmony of sweet sounds. His acquaintance with artists was large and generously enjoyed. We will not enter upon his social relations. He never assumed that “one tie” that too often separates from father and mother and natural relations. It was known to all the delightful brotherhood that that constituted the firm of “Montooth Bros.”

|

| 1889 plat map showing Montooth home |

Since he had never married (eschewing that “one tie”) and had no children, Montooth’s will stipulated that all his earthly goods be equally divided between his surviving siblings, sisters Mary and Margaret, whom he named as co-executrices of his estate.

His collection of “photographs, with autographs of famous theatrical people” most of whom were personal friends, went to the Pittsburg Press Club.

|

| Blackmore mansion in Hill District |

The house was first considered for a “….project of a new hospital in Pittsburg under the management of a society of Hebrew women.” The newspapers didn't name the organization but it was most certainly the Hebrew Ladies' Hospital Aid Society, formed in 1898 to meet the medical and social needs of newly arriving Jewish immigrants settling in the Hill District. The society had by this point raised some $7000 for their new venture, and were said by the Daily Post in October 1900 to be interested in buying “…a house which can be converted into a hospital without too much repairing.”

|

| Blackmore renovated as Montefiore Hospital |

While they considered the Montooth homestead, the Hebrew Ladies' Hospital Aid Society eventually acquired the classically styled home of the late Mayor James Blackmore further back in the Hill on Center and Herron Avenues. After renovations and expansions, Pittsburgh’s new Montefiore Hospital opened in May 1908. [i]

So why didn’t the ladies get the Montooth property?

Because Henry Clay Frick bought it instead.

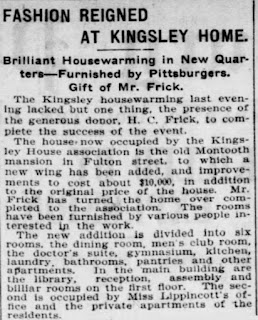

On 14 November 1900, the local press announced that Pittsburgh industrialist Henry Clay Frick had presented the old Montooth mansion to the Kingsley House along with “permission to repair and remodel the mission at his expense to meet the

requirements of the association work.”

Social Reform in Pittsburgh and Kingsley House

|

| Rev. George Hodges (1856 – 1919) |

Rev. Hodges seemed to view his wealthy parishioners as less toxically disinterested and self-absorbed than they were isolated and ignorant. He wrote that they were

….for the most part well-intentioned and good-hearted people, who think a great deal more about the poor than the poor imagine, and who do a great deal more for the poor than anybody ever finds out.

But at the same time Hodges allowed no justification for the foundation of exploitative working conditions, low wages, and substandard housing that underlay Pittsburgh’s steel empire, and determined to work within the existing system to do something about it. He was able to prick the consciences of his wealthy parishioners by emphasizing that the debasing elements of contemporary urban life had the potential to destroy the entire social fabric of the nation. Hodges called upon Pittsburgh's industrial elite to better the community from their positions of privilege by providing resources for the worthy poor.

|

| First Kingsley House, 1707 Penn Avenue |

Hodges’ new social organization was named for Charles Kingsley, co-founder of the Christian Socialist movement in London's East End. Within the space of a few years, it became obvious that Kingsley House's first home in a Strip District row house on Penn Avenue could not meet the goals of the organization. Pittsburgh was at that time experiencing a population shift, and the Kingsley settlement house in the Strip was in the middle of a community that showed little evidence of residential family growth.

On the other hand, the area we now call the Hill District was expanding as new immigrants flooded the area.

In January 1901, Henry Clay Frick bankrolled the purchase of Kingsley’s new home in the area of city wards 7, 8, and 11. Maggie Montooth “conveyed to the Kingsley House Association the Montooth homestead at Bedford avenue and Fulton street, Eighth ward, for $15,000.”

On the other hand, the area we now call the Hill District was expanding as new immigrants flooded the area.

In January 1901, Henry Clay Frick bankrolled the purchase of Kingsley’s new home in the area of city wards 7, 8, and 11. Maggie Montooth “conveyed to the Kingsley House Association the Montooth homestead at Bedford avenue and Fulton street, Eighth ward, for $15,000.”

We can’t know exactly what motivated Henry Clay Frick’s generosity, as he famously did not speak to the press and was not gregariously self-explanatory (unlike his former partner and frenemy Andrew Carnegie). It is tempting to imagine Frick and his fellow Calvary Episcopal Church congregants guiltily squirming in their pews as they listened to Rev. Hodges’ sermons, or perhaps fuming as they read his weekly Pittsburgh Dispatch columns. After all, this period of progressive social thinking also encapsulated Pittsburgh's labor disputes and Frick’s crushing of the Homestead Strike.

But despite these seeming contradictions of concern (or perhaps because of them), and with credit to Rev. Hodges’ gentle handling of his wealthy parishioners, Mr. Frick was lauded as a willing and generous supporter of Kingsley House from its inception. He was described in local papers as “one of the most enthusiastic workers in the Kingsley House movement.” Like others from Pittsburgh's capitalist elite class, he made substantial start-up donations to the endowment fund which designated his entire family as Kingsley Life Members exempt from further payment of dues.

Rev. Hodges left Pittsburgh in 1894. Frick spent more and more time away from Pittsburgh at the turn of the century, but he remained invested enough here to make this contribution of a new building. Perhaps he felt the time was exactly right in 1901 for a magnificent public gesture on behalf of Pittsburgh’s poor. He was at that point richer than he’d ever been, following the dissolution of his fractious partnership with Carnegie a few years earlier and the formal merger of Carnegie Corporation into United States Steel Company.

This was also the time when the Christopher Magee-William Flinn Republican "Ring" domination of Pittsburgh politics was coming to an end after two decades of enriching its supporters through financial and real estate dealings, patronage, and organization of the city's immigrant population into powerful voting blocks -- the very population that Kingsley House was meant to serve. Frick had appreciated "Boss" Magee's support during the Homestead labor disputes and generally benefited from the patronage network that the Magee-Flinn Ring had created. But they'd had conflicts, too, and their relationship was largely one of convenience. Perhaps recognizing that the existing political machine's days were numbered (in part due to illness, since Magee had taken a medical leave of absence and would die later that year) and the power of the Ring was in decline prompted Frick to capitalize on an opportunity to enhance his reputation by supporting the type of people the Ring had manipulated over the years.

|

| Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919) |

Rev. Hodges left Pittsburgh in 1894. Frick spent more and more time away from Pittsburgh at the turn of the century, but he remained invested enough here to make this contribution of a new building. Perhaps he felt the time was exactly right in 1901 for a magnificent public gesture on behalf of Pittsburgh’s poor. He was at that point richer than he’d ever been, following the dissolution of his fractious partnership with Carnegie a few years earlier and the formal merger of Carnegie Corporation into United States Steel Company.

This was also the time when the Christopher Magee-William Flinn Republican "Ring" domination of Pittsburgh politics was coming to an end after two decades of enriching its supporters through financial and real estate dealings, patronage, and organization of the city's immigrant population into powerful voting blocks -- the very population that Kingsley House was meant to serve. Frick had appreciated "Boss" Magee's support during the Homestead labor disputes and generally benefited from the patronage network that the Magee-Flinn Ring had created. But they'd had conflicts, too, and their relationship was largely one of convenience. Perhaps recognizing that the existing political machine's days were numbered (in part due to illness, since Magee had taken a medical leave of absence and would die later that year) and the power of the Ring was in decline prompted Frick to capitalize on an opportunity to enhance his reputation by supporting the type of people the Ring had manipulated over the years.

Whatever Frick's reasons, this was certainly a grand gesture. While no publicly archived photos exist of the Montooth mansion prior to its conversion into a settlement house, enough information can be gleaned from its subsequent Kingsley House iteration to indicate that Major Montooth and his family lived in some style there in the 1880s and 1890s. The property had comfortable frontage on both Fulton and Bedford, and the circa 1870-80s three-story structure had 21 rooms.

Henry Clay Frick financed updates, renovations and expansions, including the building of a gymnasium (seen to the left in photos of the house, with arched window) and entire new wing extension. When the Kingsley House officially opened in the old Montooth mansion, Mr. Frick was rumored to have contributed a total of nearly $30,000 for the house plus remodeling and renovation. The Pittsburg Weekly Gazette described the new wallpaper and hangings in the home and the "Handsome casts of famous works of art…placed in different rooms and in the hall.” Other prominent Pittsburgh families contributed to the furnishing and outfitting of the settlement

house, and were given credit for entire rooms.

Neither Henry Clay Frick nor Kingsley house founder Rev. Hodges attended the housewarming reception on 11 November 1901. [ii]

Neither Henry Clay Frick nor Kingsley house founder Rev. Hodges attended the housewarming reception on 11 November 1901. [ii]

|

| Excerpt from Pittsburgh Daily Post article, 12 November 1901 |

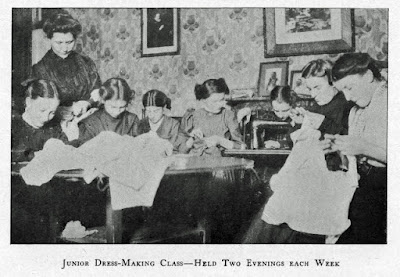

The following photos were collected from various annual reports of Kingsley Association during its tenure at the Montooth mansion from 1901-1919. The reports have been digitally preserved as part of the Kingsley Association Records held by the Archives Service Center (ASC) at the University of Pittsburgh, and can be accessed via Historic Pittsburgh Digital Research Library. Click on each photo to see it in more detail.

|

| 1906 Girls Afternoon Club holiday tree and gifts |

|

| 1906 holiday tree and gifts for Kindergarten |

|

| Holiday portrait |

|

| Visit from Santa |

|

| Playing games |

|

| Sewing ladies |

|

| Cooking class |

|

|

| Gymnasium |

|

| Kingsley House, circa 1911 |

Kingsley Association (as it was known from 1917 on) ostensibly

outgrew its well-used Montooth mansion "House on the Hill" facilities, moving to the East End in

1919. In fact, racial shifts of the population it served were what prompted this move, as

illustrated in this rather coded quote from the 1921 Kingsley Association yearbook: “The

foreign immigrant question is becoming most acute in the rapid shifting of race

residence in the Hill district.”

Service provision and support were very much racially segregated, with the new East End facilities secured to serve primarily European immigrants and their families.

For a few years after Kingsley Association vacated the premises, the Montooth mansion housed the Morgan Community House. This was a “social settlement for colored people” that was initially operated by Kingsley in cooperation with the National Baptist Mission Society, but then turned over to that organization entirely.

Service provision and support were very much racially segregated, with the new East End facilities secured to serve primarily European immigrants and their families.

For a few years after Kingsley Association vacated the premises, the Montooth mansion housed the Morgan Community House. This was a “social settlement for colored people” that was initially operated by Kingsley in cooperation with the National Baptist Mission Society, but then turned over to that organization entirely.

The same Fulton (by now called Fullerton) and Bedford property was considered in 1918 as a potential location for Pennsylvania’s only hospital for African-Americans. In 1923 it was reported that the Morgan Community House had vacated the old Montooth property and was turning it over to the Negro Hospital Association to equip as a hospital for Pittsburgh’s black population. The Morgan Community House continued to operate nearby at a property purchased for $12000 by African American community leaders at 73 Fullerton Street, and it operated for many years as a “Negro Community House.”

As for the Montooth mansion, it was demolished at some point

after 1923. A notation in a 1931 Pittsburgh Press article referencing the “House

on the Hill” states that it was “….later torn down to make room for the proposed

Negro hospital.” Since the Livingston Memorial Hospital Planning Committee

eventually settled into the site vacated by Montefiore Hospital further back in

the Hill in the old Blackmore estate, it is not clear if the Montooth mansion

ever served a public function after 1923.

Epilogue: A Philanthropic Legacy

While Major Montooth certainly had an out-sized reputation in

Pittsburgh’s legal, veteran, and cultural community during his lifetime, it was not lasting and there

is no evidence that philanthropy was part of his public profile. That such a legacy is connected to his name at all today is vis-à-vis the posthumous use of his home. The Montooth name was repeatedly referenced publicly during the 20 years that the old homestead served as a

community house for Pittsburgh’s immigrant and black communities, so the Major existed in living memory for some time after his death.

But at least one of Major Montooth’s two surviving sisters had an active share in a Montooth philanthropic legacy. After selling their family homestead, Mary and Maggie Montooth moved to smaller digs at Halkett and Forbes in Oakland until the end of their days. For nearly two decades, Mary managed the Toy Mission, a holiday gifting charity for poor and orphaned children that she helped found in 1893. The spinster sisters both passed away in the mid 1920s.

Today all we have left to remember the Montooth family is a street between Warrington and McKinley Park in Beltzhoover, in the former Montooth Borough, which was named for the Major in the 1890s.

But at least one of Major Montooth’s two surviving sisters had an active share in a Montooth philanthropic legacy. After selling their family homestead, Mary and Maggie Montooth moved to smaller digs at Halkett and Forbes in Oakland until the end of their days. For nearly two decades, Mary managed the Toy Mission, a holiday gifting charity for poor and orphaned children that she helped found in 1893. The spinster sisters both passed away in the mid 1920s.

Today all we have left to remember the Montooth family is a street between Warrington and McKinley Park in Beltzhoover, in the former Montooth Borough, which was named for the Major in the 1890s.

[i] Montefiore Hospital at Herron and Center soon outgrew its site, prompting extensive fundraising, acquisition of new property in Oakland, and a building campaign. Today’s Montefiore Hospital was established in Oakland in 1929.

[ii] A blurb in the 3 November 1901 Pittsburgh Press indicated that Kingsley House was “looking forward to the prospect” of Rev. Hodges and Mr. and Mrs. Frick attending the reception. But Reverend Hodges was Dean of Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts and was unable to attend, although he sent a telegram of congratulations to be read aloud at the event. It is not known why the Fricks didn’t attend. It’s possible that a previous commitment or travel plans took precedence. Perhaps the terminal illness and death of his uncle Jacob Frick in Wooster Ohio that same week served as a social excuse. In general, it seems that HCF did not seek the public approbation for his good deeds with the same enthusiasm as did his former colleague Andrew Carnegie. Also, given Frick’s focus on travel and work in NYC at the turn of the century, the goings-on in Pittsburgh were perhaps less important than they once were. And it is quite possible that the organization itself became less of a priority as it shifted to a more activist reformist stance. Kingsley Association and the surrounding area served as ground zero for the scathing, widely-publicized Pittsburgh Survey, a ground-breaking sociological study of urban poverty and industry. Although always listed as 'lifetime members’ in recognition of their initial generosity, Frick and his family members were not listed as repeat donors in Kingsley Association annual reports.

__________________________

Please email me

at historicaldilettante@gmail.com if you have questions about specific sources consulted for this piece. For more information about

the reform era in Pittsburgh, I recommend Keith A. Zahniser’s Steel City

Gospel: Protestant Laity and Reform in Progressive-Era Pittsburgh.