What to say about someone whose contributions have been astronomical?

If you are an astronomy buff, or know about the history of the City of Allegheny and Pittsburgh's North Side, John Brashear's name will resonate. He was a polymath of the late 1800s and early 1900s who hobnobbed with all the luminaries who populate this city's history of that era. He was renowned for his self-taught innovative lens and optics work, his stellar reputation as a scientific educator and administrator, his abiding love for his wife and work-partner Phoebe, and his humanitarian endeavors.

And he was so beloved by Pittsburgh that the entire city called him "Uncle John."

Brashear's life story is inspirational for lessons learned about resourcefulness, believing in oneself, making the most of opportunities, and giving back to society.

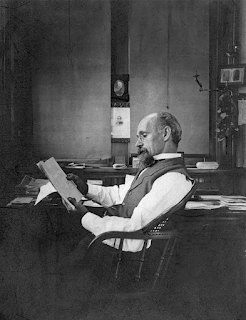

|

| John Brashear, 1910. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

John Brashear was born in Fayette County in 1840. He fell in love with the stars at age 9 when his maternal grandfather gave him the opportunity to view the rings of Saturn through a traveling telescope. From humble origins as a Brownsville tavern-owner's son through early days working in a grocery store and various machine shops, an enduring love of astronomy and applied science drove Brashear to work on fashioning a better telescope lens. For five years he held a full-time mill machinist job by day and tinkered by night in a coal shed behind his South Side Slopes home, with full support of his wife Phoebe.

|

| John and Phoebe Brashear, circa 1862. University of Pittsburgh. |

A literally crushing set-back occurred when Brashear broke his first finished lens. He persevered to recreate and prefect a five-inch telescope lens, state-of-the-art due to Bashear's pioneering silvering technique. Brashear presented this lens to Samuel Pierpont Langley, Director of the Allegheny Observatory and Professor of Astro-Physics.

|

| Samuel Pierpont Langley, |

Langley (who became the third Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution) offered to mentor and collaborate with Brashear, bringing him into the Observatory fold to create lenses and other precision scientific equipment.

|

| Brashear's optical shop, c 1914. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

In turn, Brashear's work facilitated Langley's solar research, standardization of accurate timetables, and experimentation with flight theory vis-à-vis the aerodrome. Langley's successor, James Keeler, did pioneering spectrographic observations of Saturn's rings that would not have been possible without Brashear's precision instrumentation.

In 1881 Brashear came to the attention of railroad tycoon William Thaw, who became his primary financial benefactor. With his research, travels, and a new workshop subsidized by Thaw, Brashear went on to revolutionize the field of astronomy with his advances in instrumentation.

Having never forgotten his chance to peer through a telescope as a young boy, Brashear was committed to making scientific findings available to all comers. He never patented or restricted his work, and he made sure that the newly-constructed Allegheny Observatory was publicly accessible.

| First Allegheny Observatory, c. 1886. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

| Second Allegheny Observatory construction, c 1913-14. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

At his insistence, the building included a public hall that hosted a lecture series funded by industrialist tycoon Henry Clay Frick.

| Allegheny Observatory Lecture Hall, 1910-20. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

The public was also invited to use the telescopes -- a great boon in May 1910 when Halley's Comet passed through. So great was Pittsburgh's astronomical interest that year that the observatory had to distribute free tickets to manage crowds wanting to peer through its telescopes, welcoming as many as 200 visitors per night when the comet was most visible. "Crowd of people made their way toward the observatory last night, and I don't suppose I have ever seen so many people looking at the sky at one time...." commented Observatory director Schlesinger at one point to the Pittsburg Press.

| Pittsburgh Post, 16 May 1910 |

Public accessibility was a critical concern for Brashear, as he wrote in his autobiography:

In my early struggles to gain a knowledge of the stars, I made a resolution that if ever an opportunity offered or I could make such an opportunity, I should have a place where all the people who loved the stars could enjoy them;...and the dear old thirteen-inch telescope, by the use of which so many discoveries were made, is also given up to the use of the citizens of Pittsburgh, or, for that matter, citizens of the world.A strong believer in the moral necessity of doing one's civic duty, Brashear served as Acting Director of the Allegheny Observatory and was its primary fundraiser. He was also Acting Chancellor of the Western University of Pennsylvania (now the University of Pittsburgh). Modest and wishing to remain focused on the work he loved best, he refused permanent positions in both cases. He was also a member of the founding committee of Carnegie Technical Schools (now Carnegie Mellon University); organized and served as Chairman of the Henry Clay Frick Educational Commission at Mr. Frick's personal request; and served as president of multiple professional engineering and science societies. Brashear's formal education consisted of one semester at a business school, but his work garnered him countless awards and honorary degrees. Brashear and his wife Phoebe were great benefactors to their community. In 1916 a settlement house and community center were established on the South Side in his honor, and this Brashear Association remains active today.

Brashear's star shone far beyond the skies of Pittsburgh and many of his instruments actually remain in regular use. Even Einstein owed him a debt of gratitude, for the Theory of Relativity was developed using a mirror that Brashear designed in 1886. My favorite Brashear accolades are the craters on the far side of the Moon and on Mars that were named for him.

| ||||||||

| Brashear Crater on Mars. Source: Wikipedia Commons |

| Photograph of moon taken through Allegheny Observatory telescope, c. 1910-20. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

John Alfred Brashear died on April 8, 1920 after suffering for six long months from the effects of food poisoning. His ashes were interred in the Allegheny Observatory crypt, along with those of his beloved wife Phoebe. An excerpt from the Sarah Williams poem I quoted at the start of this entry is their epitaph.

So how is it that such a luminary, a man so popular in his day that he was known as "Uncle John" to the citizens of Pittsburgh, a man named “Pennsylvania’s Most Distinguished Citizen” by the governor in 1915, is relatively unknown today?

Fortunately, there have been attempts to keep Brashear's light shining. He wrote an autobiography that was published posthumously. It is filled with charming anecdotes and fascinating reflections about his life and times. The book is in the public domain, and can be viewed online HERE.

The Allegheny Observatory that was so central to Brashear's life remains in Pittsburgh's public Riverview Park, owned and operated by the University of Pittsburgh. Its white domes rise above serpentine Perrysville Avenue like an astronomical Taj Mahal.

|

It is now a

private research laboratory. Free public

guided stargazing tours have been made available at the Observatory by reservation from

April through

October, retaining that public accessibility that was so important to

Brashear.

A 2009 profile about Brashear on WQED's now-defunct news

magazine show OnQ can be viewed HERE.

There have been multiple efforts to permanently and prominently inscribe Brashear's name in the history books so he's not left languishing in footnotes. Dr. Don Handley created an hour-long documentary entitled Undaunted: The Forgotten Giants of the Allegheny Observatory which premiered at the Heinz History Center in April 2012. Its release coincided with commemorations of the 100 year anniversary of the dedication of the Allegheny Observatory on August 28 1912. Undaunted highlighted the work of Brashear and his contemporaries. It's been available for public sale, and American Public Television accepted Undaunted for distribution to PBS stations throughout the nation.

I remain hopeful that such a larger scale refocusing of attention on his story can spur further action on preserving the architectural witnesses to this man's fascinating life story. Brashear's home and factory were long neglected on Perrysville Avenue of Pittsburgh’s North Side. The home, built for the Brashears by Thaw and incorporating the gracious Arts and Crafts styles of the day, is at this writing privately owned and used as a transitional living facility for rehab patients.

The nearly-adjacent factory complex of the Brashear Company has been owned by the City of Pittsburgh since 2012 but it's in poor shape, having sat derelict and abandoned for decades.

|

I've written before about how critical it is to preserve architectural witnesses to history. Sometimes empty buildings are all that is left to memorialize someone and recognize their accomplishments, and those buildings can make all the difference in keeping memory alive.

|

The legacy of Brashear's friend Henry Clay Frick benefited from his daughter Helen's decision to preserve their family home, Clayton. But there's no one left to lovingly and single-mindedly honor John Brashear through preservation efforts.

A national designation of significance for the Perry Hilltop buildings associated with him can pave the way to their historical preservation, which in turn can keep the light shining on Brashear's work.

________________________

An unwelcome update: An incredible loss for our region's history of industrial and scientific innovation occurred on Monday, 16 March 2015 when a wall of the Perry Hilltop factory collapsed. Demolition on the rest of this historic building followed the next day due to safety reasons. During demolition a 120-year-old brass time capsule was found in the former cornerstone. Later opened by the Antique

Telescope Society, contents included Brashear factory plans and

blueprints, an 1894 photograph of Brashear Factory workers, an optical

glass, letters and newspaper articles, photographs of Brashear's family and Pittsburgh VIPS, a lock of hair belonging to Phoebe Brashear, and a

copy of a book about benefactor William Thaw.

|

| John A. Brashear Company Building. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

| Craftsman at work at Brashear Company, 1914. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

| John Brashear, 1910-1920. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh. |

ARTICLE about demolition.

_______________________

Further Reading:

Advancing Astronomy and Community: John Brashear

Allegheny Observatory website

Biographical Fact Sheet

Brashear House Historical Marker

Centennial: New Allegheny Observatory Dedication

Dr. J.A. Brashear Dead Following Long Sickness

Help Achieve Historic Status for John Brashear's Home and Factory

Historical Status Sought for Brashear's North Side Home, Factory

Historic status sought for Brashear' s home and factory in Perry Hilltop

National Park Service: Astronomy and Astrophysics: Allegheny Observatory

New film stars Allegheny Observatory

Pittsburgh's Allegheny Observatory: New History Film

The Story of John Alfred Brashear, The Man Who Loved the Stars

"Undaunted" shows pioneers who reached for the stars at Allegheny Observatory

Undaunted: The Forgotten Giants of the Allegheny Observatory film trailer

Was the nomination with the National Register of Historic Places for the Brashear buildings successful?

ReplyDeleteThanks for your question. I had to ask around a bit as searching the Register isn't exactly a user-friendly process! According to Bill Callahan of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission's Bureau for Historic Preservation, both the John A. Brashear House and Factory were successfully placed in the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service on 26 December, 2012. So there's some good news for those interested in the Brashear legacy and historical preservation!

ReplyDeleteJohn A. Brashear was a member of Guyasuta Lodge #513 F&AM located in Pittsburgh. On December 15, 1925, John A. Brashear Lodge #743 F&AM was constituted. Both lodges continue to this day.

ReplyDeleteI am related to him on my Moms side and still have some family in PA. I love reading about his history and love for the stars, something that has always interested me.

ReplyDeleteI am related to him on my Mom's side and have heard many stories about him from my grandfather Basil Brashear. Very interesting stuff!

ReplyDeleteI grew up next door to Brashear's house and factory. The factory - huge, solid brick, sitting on top of a hill - always felt more like a piece of geography than a simple building. Visiting after it was torn down was sad and weird, like waking up one morning and finding that the Mon was gone.

ReplyDeleteThank you for this article.

Doug Blair

Yes, it was such a tremendous loss as an architectural witness to so much history. I'm glad I was able to get a few photos before it collapsed.

Delete