This salacious headline appeared one hundred years ago on the front page of the Pittsburgh Press.

That word, orgy? It didn't quite have the same impact that it does today. I mean, it’s always been used to conjure associations of excessive, frenzied, debauched behavior. But the sexual connotations weren’t as automatic in the 1920s.

Still, this headline got attention. It was meant to. It appeared on 24 January 1923, the same day that a Homestead mother and her three children were buried. The family had immigrated from Scotland’s Glasgow region in September 1922, only to perish barely four months later in a Homestead hotel fire.

The Winnie Family

On 22 January 1923, 26-year-old Margaret Miller Magowan Winnie died with her sons David (5) and William (7) Magowan and her step-daughter Catherine (Katie) Winnie, age 17. Margaret’s husband James Guighan Winnie, age 47, escaped the flames by crawling from their room onto a window ledge. He had awakened first and rushed to another part of the building to alert daughter Katie about the fire. He then tried to usher his family to safety on the roof, but they were unable to follow him through fire and smoke.

“Winnie was found hanging to a window ledge outside of the bedroom,” recounted Homestead newspaper The Daily Messenger. “Taken to the ground on a ladder he dashed around the building and attempted to rush into the flaming front hallway, but was restrained by firemen.”

What the papers didn’t know in 1923, but what the availability of modern genealogical records reveals, is that this was a family well-acquainted with tragic loss. Margaret’s first husband Samuel Magowan was only 31 when he died in 1918, possibly during the influenza pandemic. Maggie was left with two small sons, and was newly pregnant. Another son born seven months later did not survive infancy.

In July 1920 Maggie married James Guighan Winnie, a widower 24 years her senior who had six young adult children.

James and Margaret had a son who lived less than a year. They gathered five of their children a few months later for a new start in America, stating at immigration that they planned to settle here permanently. Three other children remained in Scotland.

The Winnies lived for a while in East Pittsburgh, but James got work as an engine oiler at Homestead Steel. The family moved into the 22 room hotel at 513 Dickson Street in early January, likely hoping to find better lodgings once James was situated in his job.

Pittsburgh Daily Post described how the Winnie family began to settle into the community:

When their father brought them to Homestead, little William and David Winnie were happy because they were to go to school together. Their mother took them one day to St. Mary Magdelene’s school in Tenth street. But David was too little. He wasn’t big enough to go to school, the sisters said. He had to stay at home while William sat in a front seat in room No.1. They were separated for the first time in their lives. They died together.

Peter (19) and Annie (25) were the other family members living in the area. Peter had been the first to arrive in the United States in July 1922, settling in Braddock. He signed a declaration of intent to become a naturalized citizen of the United States on 2 October 1922. Annie was an unwed mother, having had a son in February 1922 whom she left behind in Scotland.

In December, Peter and his younger sister Katie posed for a photo taken for Christmas at a Pittsburgh studio.

|

| Siblings Peter and Catherine Winnie, Pittsburgh PA, December 1922. Photo from Ancestry.com family history files. |

Peter was working a night shift at Homestead Steel when the fire occurred. Annie was said to be “visiting friends in Pittsburgh” according to some press accounts. Later reports indicated that she was employed and did not live with her family at the Dickson Street hotel.

Peter was the one who had to tell his father that the rest of the family had perished. After identifying the remains, the two men informed Annie. Some papers claimed that two additional Winnie children had recently sailed from Scotland to join the family, unaware of the tragedy that awaited them.

Maggie, her boys, and Katie were laid out at Gillen-Coulter undertakers in Homestead. Pittsburgh papers noted that hundreds of people “visited the undertaking establishment at 322 Eighth avenue and looked at the little burned bodies.” As barbaric as this sounds to us today, it was not uncommon following gruesome deaths for people to flock like tourists to public visitations.

Perhaps local authorities even approved of this pathetic display with good intent, hoping it might arouse sympathies and thereby help with fundraising for burial expenses. Borough Burgess John Cavanaugh had appealed to his Homestead community for donations since “the husband and father was in no circumstances to pay the funeral expenses as the fire….had left him practically penniless. Burgess Cavanaugh considers the cause a worthy one….” Thus endorsed, various papers noted that contributions could be made directly at the mayor’s office or to his wife, at the Daily Messenger office, or to any Homestead police officer.

A tally published on 31 January indicated that the community gave generously: $934.53 was raised, of which $357.50 was used for funeral expenses. Inflation calculators rarely give all-encompassing views of historical vs. current valuation, but this generally would have amounted to $17,000 today, a significant sum to collect from a working-class community. Considerable disagreement was reported about whether the remainder after funeral expenses should be donated to the Winnie family, or kept in a community trust for future tragedies. Burgess Cavanaugh emphatically informed the community about his decision in the Messenger:

Since the only dependents in the family met death in the fire, since the youngest left is 19 and is working every day in the mill, since the father has steady employment and the sister is likewise employed and since the two members of the family on their way from Scotland are aged 21 and 25 years it does not seem advisable to help those who can and are helping themselves. It was specifically stated at all times that the money was to be used for burial expenses.

Such adamant sentiments may seem harsh a hundred years on, but were in keeping with the charitable philosophy of the times which held that aid should only be extended to those “worthy poor” unable to help themselves. Collected money would be refunded should donors so request.

Maggie Winnie, her boys, and stepdaughter Katie were buried in St. Mary Magdalene Cemetery.

Thomas Davies

Hotel owner Thomas W. Davies, age 43, also perished in the fire. Known to friends by the nickname “Goat,” Davies had worked variously as a bartender and hotel clerk in the area. He rented and managed the hotel that locals referred to as the “Murphy place,” owned by a Bridget Murphy.

Davies lived on the second floor of the hotel. According to the Messenger, he awoke to smoke “pouring into his room in the central part of the hotel.” He said he first ran to awaken the Winnies one floor above in the rear, then found himself trapped as fire climbed the building walls. Firemen described how he “burst down the stairs and through a wall of flame. He rolled to the bottom of the stairs and fell unconscious on the hall floor.” Homestead Fire Chief Bryce sustained burns as he and another fireman dragged Thomas Davies from the building. Davies was taken to Homestead Hospital, where despite enormous pain he remained conscious and able to speak with friends and family. He died within a few hours.

The Davies family immigrated from Wales in 1893, and like the Winnies had known hardship and tragedy. Mother Mary died 16 years earlier when a fire destroyed the family home on Tenth Avenue in Homestead. One paper hinted at the trauma that Davies’ father must have experienced after losing yet another family member to a fire; his father “would not be consoled” and “would not leave the place where the body of his boy lay.”

Davies’ wife of 15 years “had gone to Los Angeles….a week ago to regain her health.” Whatever the circumstance this implied, Davies was able to relay her contact information to his mother-in-law. Frances Bitner Davies did not make it back in time to see her husband buried, and she was not named as a survivor in Thomas’ public obituary, but she remained on record as executrix of his will. The couple had no children.

Arrangements for Davies’ funeral were made by the Homestead Elks, where he was a member. The Messenger noted that the extensive Welsh community of Homestead turned out to pay respect to one of their own and support the surviving family. Thomas Davies was laid to rest in a family plot in Homestead Cemetery.

County Detectives Investigate

Amid such unremitting tragedy, what possessed the Pittsburgh Press to lede with a headline about an orgy at the hotel?

According to various articles, proprietor Davies got a party rolling on Sunday night by “inviting several women and men to come to his establishment." The hotel porter said this party stretched into the wee hours, with a phonograph blaring until 1 AM. The next-door neighbors claimed they “were unable to sleep owing to the boisterousness and disorder of the guests attending the party” which went on until 2 AM. The porter claimed he witnessed lit matches and cigarettes tossed around the hotel kitchen, where the fire was believed to have originated.

The Winnie rooms were right above the kitchen, marked by a cross scratched into the center of this newspaper photo.

|

| The Daily Messenger, Homestead, 24 January 1923 |

The fire’s origins were initially declared accidental, but tales

about a wild party raised suspicions that had to be investigated to rule out

other incendiary causes. “I have reasons that lead me to believe that the

Murphy hotel in Homestead was set afire,” announced the Allegheny County

Fire Marshall on the pages of the Messenger on 23 January. By the time that Press orgy

headline was published, Allegheny County authorities had already spent nearly

two days trying to identify party-goers at the hotel, possibly including

“three women from Hazelwood.” A phone number connected to that location had been retrieved somewhere, giving the investigation focus.

It was a blurry focus, at best.

Using a high-octane word like "orgy" certainly would have focused eyeballs on this story. Authorities likely hoped press coverage could help them find the partiers they wanted to question, and the Press was glad to cooperate. After all, a titillating front page headline would have helped sell newspapers! But such a story also reflected moralistic attitudes of the times, since readers intuitively understood that it was a cautionary tale about the dangers of excess and carelessness.

| Front page headline, Pittsburgh Press, 24 January 1923 |

Never mind that there may not have been a party. James Guighan Winnie said he went to bed early that night, and he denied hearing any partying, phonograph music, women from Hazelwood, or (presumably) orgiastic shenanigans in the hotel. The Chief of County Detectives admitted he had “no concrete evidence” about any of the allegations. Still, all the local newspapers speculated about that “gay midnight party” (another word that hits differently today) and "lighted matches and partially smoked cigarets, carelessly discarded by women and men guests."

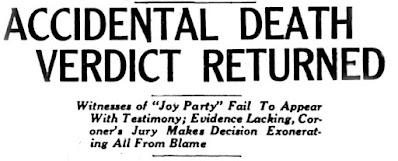

One month later when a coroner’s jury on 23 February reviewed evidence and testimony from seventeen witnesses, the deaths of the five victims of the Dickson Street fire were declared accidental. The Allegheny County coroner’s jury stated that the fire probably resulted from a gas stove "left burning in the kitchen." The Winnies had likely died of asphyxiation before the flames came near.

|

| Headline, Homestead Daily Messenger, 23 February 1923 |

What changed?

No partiers showed up to testify.

Perhaps they never existed.

According to the Daily Messenger, “Sensational testimony by persons who are alleged to have been participants in a joy party which took place in the hotel previous to the burning, failed to develop when no one appeared on the carpet to give evidence.” With no witnesses and no evidence, the “general opinion that a joy party the night of the fire was responsible” could not be substantiated.

Several other revelations from the inquest were noteworthy. According to the local fire marshal, Thomas Davies had inquired a week earlier about legal requirements to build a fire escape on his three-story property. He never got the chance to follow through. It was believed by all that a fire escape would have saved five lives that night.

Rumors had floated that complaints had been submitted about certain fireman. Testimony before the coroner’s jury disclosed that a fight occurred at the fire scene between responding Homestead and Munhall fire departments. “Rivalry between the two companies when either of the departments go into each other’s respective territory was given as the reason. The chief declared the trouble did not start till the fire had been practically extinguished.” Regardless of whether it interfered with their duties, the Allegheny County coroner was not best pleased to learn that these fireman had acted like jagoffs. He rebuked Homestead Fire Chief Bryce.

For his part, Bryce, who had suffered burns when rescuing Davies, admitted in his testimony that he and his men did not search the premises once they removed Davies from the building. He claimed they learned about the presence of Mrs. Winnie and the children "too late" to do anything, as there was no way to access the family trapped by smoke, a burning staircase, and locked door on the third floor.

In light of departmental rivalry and overall unprofessional behavior, the coroner called for a reorganization to place Homestead’s “fire department on a plane that will be consistent with the practice of modern protection.” Chief Bryce later responded with a statement agreeing with that recommendation. He complained that he had twelve firefighters working three companies in a borough that could use nearly twice as much manpower. He also stressed the need for a hook-and-ladder truck but claimed that since Homestead council had done nothing with that request to date, the department was making do with an antiquated hose wagon.

Bryce nonetheless defended the work of his poorly staffed and equipped department, and claimed that “out of one hundred runs before the hotel fire the damage by fires was only $4,470.”

He did not mention anything about fatalities.

The Homestead newspaper seemed embarrassed on behalf of the

community by the Allegheny Coroner's rebuke. The Messenger defensively noted that “attempts seem to have been made to make

Fire Chief Bryce the “goat” in the matter.” The paper was also sympathetic to

the obstacles Bryce faced in dealing with an incompetent and ineffective town council

that operated with “rank indifference to the best interests of the community

(and) utter disregard for the safety and comfort of the citizens.” But the paper insinuated that a better man could

rise above the politics that handicapped his department to find solutions, noting that “….Chief Bryce may

not be up to the mark held by his father as a Fire Chief.” The senior Bryce, revered in the community as founder of Homestead glass works, established the first independent fire company in Homestead in 1880 when the Borough incorporated as a municipality.

Lost in all of this? The Dickson Street hotel fire was chalked up as just one of those sad, sad things.

Coda

James Winnie, Jr. left Glasgow on January 27th to join his family in Homestead. He traveled alone, arriving at Ellis Island on 5 February 1923. His reunion with remaining family members, possibly prior to the coroner’s inquest, was not covered by any press. Reporters were done with the Winnies.

But so, too, was the Winnie family mostly done with Pittsburgh. Three months later, James Guighan Winnie and his daughter Annie left New York to return to Scotland. James would marry for a third time and spend the rest of his life in Scotland. Annie, reunited with her firstborn, married in Scotland then briefly returned to Homestead a few years later, where a second son was born. Her branch of the family stayed in the United States. Although brothers James and Peter traveled back and forth to the USA and Canada, they made permanent homes in the United Kingdom. The USA seemingly held no attraction for two other Winnie siblings.

The building at 513 Dickson Street was demolished. Modern Allegheny County Housing Authority high rises stand there today.

No comments:

Post a Comment