Every winter we are inundated with stories about the latest horrible, no good, very bad flu season.

In the United States, flu season peaks between late December and early March, which is when we work ourselves up about potential epidemics and lethal strains.

Such flu-panic is nothing new; in 1943, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette warned readers that "The flu epidemic of 1943 may approach in severity the deadly one of 1918." It didn't, but that didn't stop the paper from admonishing its readership: "Without getting panicky, the public must co-operate with public health authorities in every possible way to check the spread of the disease. The best way is for each individual to safeguard his own health and treat flu, if he gets it, with the respect it deserves."

Yup. Yinzers need to respect the flu, because it's serious business.

Although today we have no collective experiential understanding of what plague is like in the Western world, history teaches that the threat of an über-illness ought to give us pause for concern. Influenza pandemics have occurred three times in the past century (1918-19, 1957-58, 1968-69), each caused by different but related subtypes. Many scientists believe it's only a matter of time until another influenza pandemic occurs given the efficiency with which these viruses can replicate, spread, and mutate, with international communication and public health efforts struggling to keep up.

In 1918 the power of illness devastated Pittsburgh due to a complex interplay of viral and societal factors

In the Grip of La Grippe

What we call the "Spanish" flu was thusly named because Spain, the first country to be struck by the disease that wasn't involved in World War I, was not constrained for the "good of morale" during wartime to censor health reports. That's what other countries, including the United States, were doing. Since people first started hearing about the flu in Spain, that country got to claim ownership of it.

News broke in the United States in March 1918 when military health officials at Fort Riley in Haskell County, Kansas reported on the unusually virulent influenza that they were seeing there, which paralleled a concurrent outbreak in Europe among the military population.

Newspapers duly reported on the influenza epidemic throughout 1918, but at first it seemed far away. War news and the Pirates pennant race dominated headlines during the first half of 1918 in Pittsburgh. The nation tried to make light of the flu even as domestic disaster loomed. Click on the cartoon below for an example of such flu-humor:

|

| Reprinted in Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 13 August 1918 |

The second and most virulent wave of the influenza outbreak occurred in the fall of 1918. which is when the disease truly spread to the civilian population. A third and final wave occurred in the spring of 1919.

The influenza pandemic of 1918-19 killed an estimated 20 to 50 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 deaths in the United States. There's certainly a big gap between 20 to 50 million, and it reflects the lack of documentation during this time. Such a lack of accurate record-keeping might astound modern readers, but the national Public Health Service had only recently begun to require regional health departments to report on disease incidence. And influenza wasn’t initially a reportable disease.

Eventually the flu was mandated as reportable by state agencies, but such a staggered approach did little to assure accurate data collection. The illness was so widespread, and states had different reporting standards. Coordination of data reporting simply wasn't possible. Many, many cases went unreported.

Just as epidemiological data-gathering fell short of today's standards, so too were seemingly sensible precautions lacking in 1918. Today we know that avoiding crowds is wise during flu season because viruses can spread quickly through airborne particles. In 1918, public health officials thought catching the flu was the result of bacterial infection. They sought to minimize exposure through the wearing of gauze masks, even passing laws requiring public wearing of such masks.

We know now that masks don't effectively filter viruses in the air. Eventually people figured that out in 1918 from sorry experience, but thousands sickened after exposure at events like war rallies and parades.

|

| National public safety advice reproduced in Pittsburgh Daily Post, 10 October 1918 |

In fact, the Great War itself was a huge factor in the epidemiological case history of this illness. The virus first spread to the United States from that military base in Kansas, with subsequent incubation and widespread incidence of the illness on troop carriers well-documented.

Who Got Sick?

|

| Warning posters like these were posted in public places |

Entire families sickened and died within days, with no one to care for them due to the widespread nature of the illness, fear of contagion, and decimated medical corps due to wartime service needs.

Try to imagine how many people died in the United States as the equivalent of ten modern football stadiums filled with dead people.

The flu took three times as many lives as did World War I itself.

And even if you somehow escaped being infected (and there were many who did, perhaps having developed antibody resistance from the aforementioned 1890s flu outbreak), you were still affected socially and psychologically.

Pittsburgh Gets the Flu

Despite the fact that Pittsburgh had higher overall death rates, stories about the effects of this city's experiences with the 1918 pandemic have been eclipsed by the health crisis in Philadelphia, which was an epicenter of the second wave of the pandemic.

A ship from infected Boston docked in Philadelphia in September 1918, and cases of influenza were diagnosed soon thereafter at the local Navy base. Within 24 hours, 600 sailors had been diagnosed. The virus quickly spread to the civilian population through exposure at large-scale gatherings like Philadelphia's Liberty Loan Parade.

|

| Philadelphia Liberty Loan Parade. Even as this photo was taken, all those nice people in the crowd were giving each other the flu. U.S. National Archives photo |

Then it gradually spread to west.

Urban living conditions here provided fertile breeding grounds for disease. Pittsburgh was still the place writer James Patton had described in 1866 when looking down from Mount Washington as "hell with the lid taken off," a place where "...we inhale death while enjoying every breath we draw." Overcrowded, sub-standard housing and abysmal environmental conditions contributed to the city's vulnerability, and escalated the influenza mortality rate.

So, too, did reluctance by the media, political and public health officials to acknowledge and define the scope of the disaster. Pittsburgh's official response to the epidemic may have worsened the experience for its residents. Political, industrial, and public health domains faced off against one another in a city already stretched to its limits due to the war effort.

|

| Pittsburgh Daily Post, 16 September 1918 |

But Board of Health officials also attempted to minimize the flu's reach, claiming that Pittsburghers would likely suffer from the less serious "Boston variety" and not the deadly "Philadelphia strain."

Of course, there was only one flu.

Did Pittsburgh officials really believe such strain-parsing in an orgy of self-reassurance and self-denial? Or was this an attempt at spin control to avoid panic?

There was certainly precedent for spin control during national epidemics. The New Orleans press was deliberately complicit in not reporting about its notorious yellow fever outbreak of 1853. The local papers buried the news until that city was too wretchedly ill to deny its presence.

Whether politically expedient denial in the name of impression management and economic pressures, or misguided attempts to maintain morale, Pittsburgh paid the price. City leadership initially refused to accept offers of aid from the state's Red Cross, even as reports about the disaster in Philadelphia escalated. Reluctance by media, Mayor Edward V. Babcock, and Pittsburgh's Board of Health to publicly acknowledge the full extent of the epidemic damned Pittsburgh to suffer.

The disease had probably manifested in Pittsburgh by late September, although the press claimed at the time that Pittsburgh had been "passed up." Even with that overly optimistic prediction, the papers noted that official "warnings sounded" because danger from an epidemic was "ever prevalent."

|

| The Pittsburgh Press, 30 September 1918 |

With his death, suddenly cases of the flu were mandated as reportable.

Things went from bad to worse. On that same day that Patterson died, the Army commandeered the 150-bed Magee Women's Hospital to care of military flu victims.

The papers noted that 25/30 reported cases of flu in Pittsburgh were also being treated at the same hospital where Paterson died, but emphasized that the afflicted were all military personnel.

Surely no one was fooled. On the eastern seaboard, the flu had clearly not been confined to members of the military. In an attempt at containment, Pennsylvania state government instituted a mandatory gathering ban. All across the state, people were ordered to stay at home.

But Pittsburgh resisted.

Staying Well vs. Making Money

Pittsburgh's political leadership balked at what it felt was arbitrary and unnecessary interference from the state.

The local media duly reported on this city-versus-state power struggle. Pittsburgh Mayor Babcock peevishly declared in a statement to the press:

But they really didn't want to."The State Department of Health has full power. Personally, it appears to me, in view of local conditions and in the absence of any epidemic of influenza, that the orders of the Department are too drastic. However the State is in command, and the city authorities will enforce its order to the strictest letter."

Edward V. Babcock, Mayor of Pittsburgh 1918-1921

Why? Because, money.

Pittsburgh businessmen who relied upon revenue earned at local watering holes, hotels, restaurants, theaters, dance halls, pool rooms, and sports events exerted pressure for their establishments to stay open. Ban enforcers were encouraged to look the other way as these businesses continued to operate, and there was talk about unified resistance to the state ban.

Local papers didn't quite seem to know who to believe, as this equivocal editorial indicates.

|

| The Pittsburgh Press, 4 October 1918 |

But at the same time it was expressing doubt about the need for a gathering ban, the press reported on the city's compliance with the state order in tones that praised obedience for the sake of public health.

|

|

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 5 October 1918 |

A month later, Mayor Babcock lifted the public gathering ban in Pittsburgh earlier than was recommended by the State -- just in time for election day.

|

| Pittsburgh Post, 2 November 1918 |

"Our darkened streets and deserted assembling places, by reason of this ban has thrown over the community a depression and a pall that seriously retards the recovering to normal conditions of health, business and recreation and can but enhance further dangers from the affliction through which we have passed," wrote Babcock in his proclamation.

Meanwhile, the State Health Commissioner called this "an invitation to lawlessness and disorder" and impugned the Mayor's actions as being influenced by "liquor interests". He was probably right, for Babcock had weathered insistent pressure from closed bars and booze whole-sellers to lift the ban.

The city and state exchanged testy words throughout the epidemic, each struggling to assert authority whilst containing the disaster. The State won out in the end, prosecuting Pittsburgh businesses that defied the ban with stiff fines.

Meanwhile, more people got sick. More people died.

The official deception, inveigling and obfuscation is exemplified by this response by William H. Davis, local Board of Health director, on 10 October 1918. After reporting various alarming statistics, including 659 new cases of the flu in the previous 36 hours, the Post-Gazette reported:

Asked if the disease is to be regarded as having reached the epidemic stage, Health Director W.H. Davis said: "You must draw your own conclusions. What constitutes an epidemic is a matter of opinion."Never mind that three days earlier, his department had ordered city hospitals to operate on an emergency epidemic basis by admitting only the sickest patients and postponing nonessential surgeries.

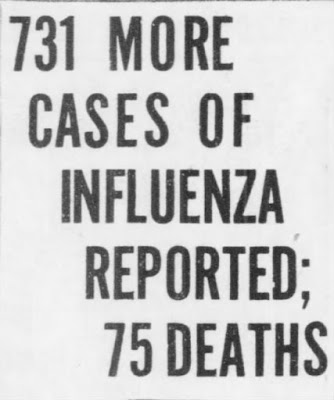

Two weeks after Charles N. Patterson's death, this was the 18 October 1918 headline in the Pittsburgh Post:

But what constitutes an epidemic is a matter of opinion.

Giving the flu the respect it was due by telling the truth about its virulent hold on the city might have helped contained the spread of the disease. City officials could and should have done better for residents. Initially there were no mandatory closures of churches, though many did voluntarily shut their doors. Eventually the city caught up and ordered church closures. But city public schools remained open until October 24, far into the epidemic, ostensibly so that the public health director could monitor and track the rate of transmission of the illness among school children.

A City Afflicted

Imagine these Pittsburgh scenarios: garbage piling up on the sidewalk outside your house because there weren't enough healthy workers to collect the trash; businesses shutting down because there were no healthy employees; schools emptied as children sickened and died; a communication vacuum leaving the fates of your friends and families unknown due to inconsistent telephone and postal service. In some cities, funeral parlors ran out of caskets, bodies went uncollected in morgues, and trenches were dug for mass civilian burials.

|

| American Red Cross training class, Fifth Ave High School, June 1918. Little did they know what was to come. Pittsburgh Public Schools Photographs, Detre Library &Archives, Heinz History Center |

It was Red Cross networking that organized railroad delivery to Pittsburgh of caskets made elsewhere. The Red Cross requisitioned city street-cleaners to fill in as gravediggers. Red Cross ambulances and trucks were loaned to the city to transport bodies. Red Cross workers arranged for enough hospital supplies, drugs, and vaccines for Pittsburghers.

|

| Red Cross nurse, Pittsburgh flu hospital, early 1900s. Allegheny Observatory Records, University of Pittsburgh |

Pneumonia was the shadow-killer of this epidemic, attacking flu suffers at the point of their weakest immunity. In an age without antibiotics, people had to rely on luck, prayers, and solicitous care by loved ones. Since WWI had left many communities short of doctors and nurses, trained medical care was hard to come by. But because this epidemic was so virulent, many families were left without healthy members to care for their afflicted.

Again, it was the Red Cross that stepped in to organize and coordinate nurse recruitment and emergency patient care. Red Cross volunteers even provided hot meals when desperate family situations were identified.

|

| Sketch of Red Cross Nurse by Childe Hassam, 1918, from Carnegie Museum of Art |

On 20 October 1918, city hospitals reached their full capacity. Pittsburgh's settlement houses were called into service.

|

| Kingsley House, c. 1913. Kingsley Association records, University of Pittsburgh |

New cases were sent to the Kingsley House, a settlement house that had voluntarily suspended its normal operations to operate as an emergency hospital. Resources and equipment were brought from Kingsley's satellite Lillian Convalescent Rest and Fresh Air Homes. Its large urban complex in the expanded former Montooth mansion in the Hill District opened its doors for some 300 sick Pittsburghers.

|

| Irene Kaufmann Settlement House for the Jewish immigrant community, Hill District, May 1922 Oliver M. Kaufmann Photograph Collection of the Irene Kaufmann Settlement, University of Pittsburgh |

The Irene Kaufman Settlement House in the Hill functioned as an emergency hospital as well, caring for 1047 cases of influenza/pneumonia in 42 days.

But even that wasn't enough.

The city set up a tent to house an additional 300 recuperating flu sufferers just below Kingsley House and old Central High School, on the Washington Park playground. This was in accordance with the popular idea that exposure to open air helped thwart progression of the disease.

Even the Courthouse annex on Ross Street was commandeered as an emergency influenza hospital on 26 October 1918. A week earlier, the criminal court and grand jury rooms had been fumigated with formaldehyde candles as a preventative and sealed for 24 hours, with guards stationed at the doors to explain why the rooms had been closed. Justice would have to wait a few weeks while those rooms served another purpose.

Although Pittsburgh officials were reluctant to declare a medical emergency, local businesses had no hesitation at capitalizing on the concerns of residents. The daily papers were filled with ads that October for products referencing influenza, like these from the Pittsburg Press:

|

| Excerpt from Rosenbaum department store ad |

Jim Higgins, Ph.D., Professor of History at Kutztown State University, detailed in a July 2010 article for the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography how Pittsburgh's experience of the 1918 pandemic both mirrored and differed from that of other hard-hit urban areas. Although accurate estimates are impossible, Higgins' sources indicate that the city lost between 4800 to 6600 people to the flu, roughly one percent of its total population.

To visualize this, imagine the Byham Theater, Benedum Center, and Heinz Hall for the Performing Arts all filled to capacity with dead bodies.

Cautionary Tales and Future Concerns

As illustrated by the aftermath of domestic disasters like Hurricane Katrina, there are valid reasons to assess the confidence we place in official abilities to effectively and efficiently manage large-scale relief efforts. We can but hope that enlightened minds will prevail if faced with pandemic conditions in the modern era, and trust that disaster relief agencies are kept fully funded.

Because the big fear, of course, is whether a 1918-like pandemic could happen again.

The flu of 1918 died out eventually. Exposure to the 1918 virus (which has been reconstructed and studied by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) is thought by some microbiologists to have conferred protective status through development of antibodies to neutralize exposure to subsequent related viruses. Two other influenza pandemics of the 20th century were rendered less virulent by a likely combination of collective 1918 antibodies. What has also made a difference are modern public health policies, and a enlightened understanding about infection precautions once the influenza disease process was recognized in the 1930s.

Viruses like the one responsible for the 1918 pandemic circulated among humans until 1957. They then seemed to die out, although a related virus re-emerged as "swine flu" in 1976. Anyone exposed to those viruses may have developed some resistance.

But no one is naturally immune to influenza, and other new strains of viruses develop that have potentially devastating lethal capabilities. New strains appear every year, and modern medicine struggles to keep up with it all. Health officials must choose influenza strains for vaccine makers to target months in advance, which makes it difficult to know precisely what strains will be circulating. And even when flu vaccines are well-matched to that year's circulating viruses, effectiveness is about 60% at best. Vaccines tend to work better against influenza B and influenza A (H1N1) viruses, offering lower protection against influenza A (H3N2). The 1918 pandemic involved a strain of the influenza A (H1N1) virus.

Yinzer Herd Immunity Won't Protect You

We are fortunate to live in an age when health care and vaccines are readily available, and research can be conducted on identifying and eradicating new diseases. Even so, there are those who have considered objections to flu vaccines. Certainly no vaccine is effective against all virus strains, or even wholly effective against the ones it targets.

But the lessons of 1918 speak to the need for each of us to do everything we can as individuals to prevent widespread disease-spread devastation. That includes getting vaccinated.

I worry that lack of personal experience leads to complacency in the face of danger. If you've known even one person who suffered from polio, for example, logic and compassion dictate that you'd be hard-pressed to forgo a polio vaccination for your child. But as our population ages and there are fewer polio survivors as a result of natural attrition, the devastation of that disease is less immediate. Complacency makes its eradication seem less of an immediate concern, and vaccination becomes less important.

Reliance on herd immunity becomes a temptation.

But the 1918 pandemic has lessons to teach those who are tempted to forego a flu shot.

Yes, the flu will pass. But it might take you with it.

Mostly out of sheer laziness, I have not always been a flu shot advocate. That changed due to an odd convergence of experiences. After my youngest child was born, I passed time in the wee hours between his nocturnal feedings researching my family history. I made many late night discoveries, including documenting a young family whose members had all died within days of one another in the fall of 1918. At the time, I was reading Mary Doria Russell's Dreamers of the Day. The protagonist of this book comes into her own following her family's demise as a result of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Russell's eloquent descriptions of the personal and communal trauma inflicted by the pandemic were wrenching. So the connection was immediate to me; I knew what had happened to my vanished family members in 1918.

I remember cuddling my baby boy, who was unable to receive a flu vaccine because of his egg allergy. Most influenza vaccines contain small amounts of egg protein.

Herd immunity wasn't fail-safe. I could get the flu and be miserable.

But he could get it from me and die.

I got a flu vaccine the next day, and have done so every year since even though my son has long since outgrown his egg allergies. It's the responsible, sensible thing to do.

Such is the power of narrative to inform and transform, even the narrative of well-researched and written historical fiction.

We owe it to ourselves to pay attention to stories from the past. No one alive today has a lived experience of the 1918 pandemic. There are, however, countless recorded histories and stories that can make history real to us in the present day. Those stories have lessons to teach about managing the future.

We must pay attention. We must give the flu the respect it is due.

__________________________________________________________

Further Reading:

10 Things to Know about the Flu

1918 Spanish Flu Pictures

Digital Encyclopedia: The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919

Bristow, Nancy K. American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.

Higgins, James. “With every accompaniment of ravage and agony”: Pittsburgh and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918–1919." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 134, No. 3 (July 2010), pp. 263-286. Published by: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Iezzoni, Lynette. Influenza 1918: The Worst Epidemic in American History

Jones, Marian Moser. The American Red Cross and Local Response to the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: A Four-City Case Study

Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Implemented by US Cities During the 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic

NOVA: 1918 Flu Expert Q&A

Studies on epidemic influenza :comprising clinical and laboratory investigations, University of Pittsburgh, 1919.

Springdale memorial remembers those who died in 1918 flu epidemic

The Great Pandemic

The Great Pandemic: Pennsylvania

The Real Reasons Kids Aren't Getting Vaccines

Russell, Mary Doria. Dreamers of the Day.

White, Kenneth A. Pittsburgh and the Great Epidemic of 1918

No comments:

Post a Comment