14 February, 1861

Some people get flowers for Valentine's Day, others get candy. On this day in 1861, Pittsburgh got a speech delivered in person by President-Elect Lincoln from the balcony of the Monongahela House, the poshest hotel in Pittsburgh.

Abe Lincoln's Pittsburgh Visit

As president-elect, Lincoln had set off on a whistle-stop tour of various cities and towns en route to Washington for his March

inauguration. Since he'd received a huge majority of votes from Allegheny

County, Lincoln was intent upon paying his respects to the county that

had so thoroughly supported him. Pittsburgh was worth a visit.

A huge but sodden crowd greeted his train as it chugged into the Federal

Street Station of the City of Allegheny on 14 February 1861.

|

| Federal Street Station, c 1905. Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

Lincoln and his family

had arrived significantly later than expected because the train was behind schedule due to an accident on the rails. The Pittsburgh Daily Press commented that "If all the people congregated there had been cognizant of the protracted agony of waiting before them, they would have gone home and taken comfortable suppers...."

Pittsburghers damp in appearance but not in spirits awaited him, all possible ancestors of Steeler parking lot tailgators, weather be damned.

That Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago railroad station near the corner

of Stockton and Federal Streets is long gone. It was bulldozed

in 1905 to make way for a new rail pass.

But even without the actual station building to prompt commemoration,

Pittsburgh remembers Lincoln's arrival and departure from the spot. An

unassuming bronze plaque was placed in 1917 on the wall of the Post

Office at the corner of South Commons and Federal Street. That's near

enough to commemorate Lincoln's presence at the former station:

"Abraham Lincoln who arrived at this point in February 14 1861 remaining in Pittsburgh a few hours enroute to Washington DC for his inauguration."

Although today the rail line is elevated above that portion of the North Side, in 1861 the depot was situated at street level. On a biting February day, when a train passes by with whistle blaring and smoke furling, it's easy to conjure the ghostly frisson of anticipation of an antebellum crowd gathered 150+ years earlier.

They were rewarded for their long wait in the rain when Lincoln emerged, shook a few hands, and bussed some little ones on their cheeks. He then ducked into carriages with wife Mary and their three sons. The entourage crossed the Allegheny River and passed into Pittsburgh on the circa-1859 John Roebling suspension bridge, where today's Roberto Clemente bridge is at Sixth Street.

|

Lincoln family as they would have looked at the time of the Pittsburgh visit.

|

Things started to get a little wild. The military was summoned for crowd control outside Pittsburgh's Monongahela House Hotel because people were "eagerly pressing about the Smithfield entrance." Even though the weather was miserable and the hour late, the people of Pittsburgh demanded to hear the president-elect speak. Abraham Lincoln was obliged to stand on a chair outside an upstairs parlor in the Mon House lobby so he could be heard by the crowd below. The weary, wet President-Elect limited himself to a few wry but optimistic remarks before retiring for the evening:

I have great regard for Allegheny County, it is “the banner county of the Union,” and rolled up an immense majority for what I, at least, consider a good cause. By mere accident, and not through any merit of mine, it happened that I was the representative of that cause, and I acknowledge with all sincerity the high honor you have conferred on me. I could not help thinking, my friends, as I traveled in the rain through your crowded streets, on my way here, that if all that [those] people were in favor of the Union, it can certainly be in no great danger---it will be preserved.

|

| 1889 image of Monongahela House exterior from eastern side of Smithfield Bridge James Benney Archives, Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center |

Abe slept that night in the hotel's Prince of Wales room, which would in later years be referred to as the Lincoln Bedroom.

|

| Staging of period bedroom with Mon House furniture. Photo courtesy Heinz History Center. |

After rediscovering Monongahela House artifacts in a maintenance building in South Park in 2006, the Heinz History Center recreated the purported Monongahela House "Lincoln bedroom" for its Lincoln Slept Here 2009 exhibit. The exhibit used a number of items from a Monongahela House bedroom, including the bed Abe was said to have slept in, a wardrobe, bureau, dressing mirror, marble-top parlor table, chairs, wash stand and even a chamber pot. Docents liked to tell visitors how long lanky Abe would have had to sleep sideways to fit upon the half tester bed.

Whether Lincoln ever slept on this furniture is debatable. It doesn't show up attributed to his Pittsburgh stay until the 1920s, and by that point the Mon House Hotel had experienced several fires and re-decorations. But even if this wasn't THE bed, it's of a certain historical style, and no harm is done imagining Abe retiring there after a long rainy day's journey.

Stepping out to a balcony at 8:30 the next morning to face "an ocean of umbrellas" shielding what was reported to be the largest crowd assembled in Pittsburgh up until that point, Lincoln's speech touched on some of the most important issues facing the nation. He advised the people of Pittsburgh that self-interested politicians were making matters worse and advised everyone to "keep cool."

I repeat it, then - there is no crisis excepting such a one as may be gotten up at any time by designing politicians. My advice, then under such circumstances, is to keep cool. If the great American people will only keep their temper, on both sides of the line, the troubles will come to an end, and the question which now distracts the country will be settled just as surely as all other difficulties of like character which have originated in this government have been adjusted. Let the people on both sides keep their self-possession, and just as other clouds have cleared away in due time, so will this, and this great nation will continue to prosper as heretofore.Sage advice to be sure, since two months later the nation lost its cool.

Antebellum and Civil War Pittsburgh

The natural association when thinking of Pennsylvania in the context of the Civil War is to recall the Battle of Gettysburg. Certainly that field of battle is worthy of lasting memory, for Gettysburg turned the tide of the war and gave rise to Lincoln's most famous speech.

But Pennsylvania's contributions to the Civil War neither began nor ended with Gettysburg. Allegheny County would live up to Lincoln's politically astute description as a “banner county” in the years to come. Pittsburgh’s strategic location at the confluence of major rivers and situated on key railroad lines made it a critical contributor to the Union war effort.

It's a challenge to imagine antebellum Pittsburgh. Our history from the Industrial Age into the modern era is well-documented, but we have comparatively few images or illustrations to show us what life was like in Civil War-era Pittsburgh. The lithographs below illustrate the antebellum Downtown area and Monongahela Wharf in some detail. In the first lithograph by Schuchman, you can see the aforementioned Roebling suspension bridge that Lincoln traveled across from Allegheny City to Pittsburgh. In the second lithograph, Roebling's very first suspension bridge across the Monongahela River is prominent. It led to Water Street and the Monongahela House Hotel. Everything along the Wharf area in the second lithograph has been replaced by the Parkway East roads.

|

| View of Pittsburgh PA by William Schuchman, 1859 |

|

| Ballou's Pictorial, 21 February 1857 |

When news of the attack on Fort Sumter reached Pittsburgh in April 1861, just a few short months after Lincoln's visit, a Committee of Public Safety consisting of 100 prominent Pittsburghers immediately formed. Subcommittees began to recruit troops in response to President Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to serve the Union. Existing military

companies and new volunteers combined. They began basic training at places such as Camp Wilkins in Pittsburgh’s Strip District, located between 29th and 32nd Streets from Penn Avenue to the railroad tracks. Nearly a dozen temporary military encampments of varying sizes sprang up around the city, as recruits gathered and crossed through this area en route to points south.

Over a four year period, nearly 26,000 men from Allegheny County responded to calls to arms. That’s 15% of the region’s total population of the time, second only to Philadelphia County in terms of the number of men who served from a particular region in the state.

This county raised over 200 companies of infantry, cavalry and artillery units in which those men served.

Along with at least one dog.

| Carte de visite, Library of Congress |

Dog Jack was a white and grey bull terrier. He was the mascot of the Niagara Fire Company of Pittsburgh, located at Penn Avenue near 15th Street in Lawrenceville. When the men of that company volunteered for service with the 102nd, they brought doggo Jack with them. Dog Jack charged front lines during battle, understood bugle calls and orders from the men in his regiment, and even sought out the wounded after battle. He was with his regiment from 1861 to 1863 and thus present at the siege of Yorktown and the battles of Williamsburg, Fair Oaks, and the Pines. Poor Dog Jack was even severely wounded at Malvern Hill.

For his troubles, Jack became a prisoner of war when captured by the Confederate Army at the battle of Salem Church VA. After being held for six months, Jack was exchanged for a Confederate soldier and returned with

his regiment (one wonders how that particular Confederate soldier felt about the exchange).

Jack disappeared once his regiment returned to Frederick City VA in December 1864.

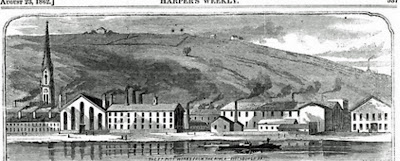

In addition to contributing men (and dogs) to the cause, Pittsburgh was a significant commercial and industrial center for the Northern effort. That seems like a a no-brainer because, after all, making stuff is what we do here in Pittsburgh. The region's economy revolved around the war effort and manufactories large and small operated under US Government Ordnance Dept contracts to contribute equipment to the Union cause. One of those, Fort Pitt Foundry, was

located in the present-day Strip district between 12th and 13th Streets along the river, near where the Heinz History Center is today.

|

| Fort Pitt Foundry from Harper's Weekly, August 1862 |

Sixty percent of all of the Union’s heavy artillery made under Government contracts came from this foundry alone, for a total of 23,000 individual pieces of heavy artillery.

|

| Negley Brigade on the Ohio River |

The Civil War even revitalized the local ship-building industry, which had declined from its heydey of the early 19th century. Wartime construction produced both sea-going and river vessels, and iron cladding produced in local mills protected four other warships and most Union ships built during this era.

Pittsburgh also provided nearly 20,000 blankets, 40,000 articles of clothing, 674 tents, and 4,000 sets of harnesses for the troops. To keep the fires of industry burning, some 5 million tons of coal were mined during the Civil War. The Pennsylvania Railroad was one of the busiest troop carriers, but all of the local railroads carried massive amounts of freight during the war years.

And of course, there was the Allegheny Arsenal in Lawrenceville, infamously known for the tragic explosion of September 17 1862 which killed 78 mostly young women munitions workers (see my blog HERE about that). The Arsenal produced much of the ammunition and military accoutrements used by Union infantry and cavalry troops during the war.

|

| Library of Congress image |

The Union government established a civilian organization called the Sanitary Commission in 1861 to raise funds to provide relief services to Union soldiers. The term 'sanitary' sounds hinky to our modern ears, but being sanitary was newly important in an era with a newly-realized importance of germ theory. Throughout the country, women worked to raise funds for wartime relief by organizing "Sanitary Fairs" in major cities. Pittsburgh's 1864 Sanitary Fair was one of the country’s most successful fundraising efforts for the troops. The Pittsburgh Sanitary Fair even inspired The Relief Polka by 19th century Pittsburgh musical luminary Henry Kleber. (Pity this piece of music is no longer in circulation; we could benefit from a little Relief Polka now and then).

There was even a Camp Wilkins Polka. But with military camp grub

where it is on the hierarchy of fine cuisine, the related dance more likely resembled the Green Apple Two-Step.

|

| Library of Congress image |

Polkas notwithstanding, Pittsburgh's industrial impact on the Union war effort was so significant that there was a very real fear of invasion by Confederate troops looking to sabotage the industrial city. A ring of 37 earthwork fortifications was built around the city in June 1862 to guard against rebel raids. Most were never finished, only one was ever garrisoned, and the majority probably weren't even armed. These defenses were never called into use, but that didn’t mean they weren’t deemed necessary as rumors of a threatened Confederate invasion swirled. The earthworks survived for several decades but there is little trace of them today.

Confederate troops did eventually come to Pittsburgh, some 118 of them, as prisoners-of-war housed in the old Western Penitentiary in Allegheny City (where the National Aviary is now situated).

There were certainly Confederate sympathizers in Pittsburgh. Confederate sympathies were undergirded by idealogies about the preservation of states' rights, but also reflected capitalistic self-preservation. Many wealthy individuals in Pittsburgh could trace the origins of their antebellum fortunes to products of Southern slave labor, given that the area's textime mills had imported and processed untold amounts of Southern cotton over the years.

Although the city's abolitionist activities have been well-documented, some prominent Pittsburgh families held slaves as late as 1857 under the classification of indentured servitude. An active branch of the controversial American Colonization Society had been established here as well. But because the city was dominated with efforts to support the Union, keeping a lower profile was prudent for those sympathetic to the Rebel cause. People of conscience were dedicated to the abolitionist cause, and Pittsburgh was a destination for slaves seeking freedom. The University of Pittsburgh has chronicled many of these

stories HERE, and the current From Slavery to Freedom exhibit at the Heinz History Center details the historical struggle for equality of Pittsburgh's African American population.

Lincoln's Legacy

Abraham Lincoln didn't visit Pittsburgh out of love on Valentine's Day. He came here to acknowledge a political debt and to pay his respects. With war looming, making an appearance in a city that had so enthusiastically voted for him was a necessary political exercise. His public affirmation for that "banner county" of Allegheny sufficed for bouquets of roses and cupid-covered cards.

Pittsburgh was fortunate to have him here in good humor. After all, Lincoln endured the miserable February weather that Pittsburghers know all too well. He was greeted by admiring crowds that were probably quite threatening in their size and zeal in those days of minimal security for politicians (Hindsight being 20/20, in Lincoln's case such security scenarios don't end well).

The Pittsburgh Gazette described the crowd outside Federal Street station the next morning as being "....unequalled (sic) for numbers and density. There was a solid mass of humanity about the depot, almost impenetrable, and the enthusiasm exceeded anything we ever before witnessed."

But the large crowds were respectful and well-managed. Only some pick-pockets in the Allegheny depot crowds marred the visit. The Gazette published a long list of victims of the thieves, but ultimately absolved them all:

These larcenies are supposed to have been perpetrated by professional pickpockets, who arrived here before the special train got in. Four or five of our most experienced thieves left the city for Cleveland, yesterday, ahead of the special train, and they will no doubt make a nice "raise" in the Forest City.The presidential cars were next headed back through Ohio, and then would re-enter Pennsylvania at Erie for the rest of the roundabout victory journey. Itinerant pickpockets staying one step ahead, city by city, to fleece crowds greeting the president-elect was some serious ground-level antebellum opportunism!

But not everyone was enthusiastic about Lincoln during his visit to Pittsburgh. Someone by the name of A.G. Frick penned obscene, threatening hate mail while Lincoln was here. Frick whipped himself into racist frenzy, while still conforming to the era's letter-writing formalities:

Sir,

Mr. Abe Lincoln

if you don't resign we are going to put a spider in your dumpling and play the Devil with you you god or mighty goddam sunnde of a bith go to hell and buss my Ass suck my prick and call my Bolics your uncle Dick god dam a fool and goddam Abe Lincoln who would like you goddam you excuse me for using such hard words with you but you need it you are nothing but a goddam Black n--g--

Your, &c.

Mr. A.G. Frick

PS ~ Tennessee Missouri Kentucky Virginia N. Carolina and Arkansas is going to secede Glory be to god on high

Consummate politician that he was, Lincoln made the most of this short Pittsburgh visit with his characteristic eloquence. He wooed an already-besotted city with words of praise, appreciation and inspiration. He won over the merely curious but also played to his base. The Daily Post opined:

On the whole he made a favorable impression upon the people, but as Allegheny is the boasted banner county of the banner state, it is also quite natural that those who gave the 10,000 majority for Mr. Lincoln....should be pleased with their representative man. -- Neither is Mr. Lincoln as ungainly in personal appearance, nor as ugly in the face, as has been represented. He is by no means a handsome man, but yet he possesses an intelligent countenance and a gentlemanly mien, and his facial features would not break a looking glass.

Lincoln forever impressed himself on the hearts and memories of Pittsburghers during this 15 hour visit, even though his 1861 Pittsburgh Valentine's Day Rest Stop would be his only time spent in Pittsburgh. The region was irate upon learning some years later that the city didn't merit a stop by Lincoln's funeral cortege as it made its sad way home to Illinois.

But Lincoln has been commemorated in Pittsburgh monuments many times over. The bronze plaque at the former North Side train station and the preservation of furniture he allegedly used while here are examples of the city's enduring reverence for the slain president. There is also a stained glass window featuring Lincoln at the historic Smithfield United Church of Christ. Heinz Chapel at the Unviersity of Pittsburgh likewise has a window commemorating Lincoln's life.

|

| Stained glass window, courtesy Heinz Memorial Chapel |

The City-County Building houses a bronze plaque of Lincoln, one of several presidential memorials dedicated in 1919 by the Pennsylvania Women's Historical Society. There's even a mysterious sculpted relief of Lincoln's profile gracing the wall along Strawberry Way on the former Arbuckle Coffee Building (The sculptures aren't original to that building, having been added in 1936 from the front of a Civil War era building that once stood on Liberty Avenue). A display case at Soldiers & Sailors Memorial houses a pre-presidential bust and an 1865 life mask, which together present a vivid picture of how the strain of those eventful 4+ years aged the man. There's even a much-stolen and vandalized circa-1916 copper statue of the man that has stood for years along Lincoln Highway at Penn Avenue and Ardmore Boulevard in Wilkinsburg.

Lincoln turns up in the most unexpected places. He's just cool like that.

______________________________________

For more information about Pittsburgh and the Civil War:

Butko, Brian and Nicholas P Ciotola. Pittsburgh: Industry and Infantry: The Civil War in Western Pennsylvania. Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. April 2003.

Fox, Arthur B. Pittsburgh During The American Civil War, 1860 1865. Chicora PA: Firefly Publications. 2009.