Pittsburgh has always been this nation's industrial center. Before we were the Steel City we were the Iron City, and arguably we could also have called ourselves the City of Glass or even the Steamboat City.

All of those titles illustrate Pittsburgh's role in shaping this country, often quite literally in terms of infrastructure production. Still, unless it's about the making of steel, we tend toward a communal inferiority complex when it comes to recognizing our central place in national history.

Everyone, at any point in time who aspired to national prominence has had a connection to Pittsburgh. Some stayed here, some strayed; some got rich and some didn't. The list of important Americans whose careers were shaped between these three rivers is mind-boggling.

Take, for example, Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe, one of the first formally-trained, professional architects in the United States.

(He was also, it must be said, a hottie).

|

| Benjamin Henry Boneval Latrobe, 1804, by Charles Willson Peale |

Latrobe has been described as the "Father of American Architecture" and credited with professionalizing architecture in this country. The way he thought about building design had a profound effect on architects up until the Civil War era. He spent at least a year of his life in Pittsburgh, but that time period is usually glossed over in biographies of this man.

| Charles Frederick von Breda portrait of Latrobe, c. 1790 |

Born to a Moravian minister in a small town near Leeds, England, Latrobe acquired extensive education and traveled throughout Europe. Following the death of his first wife, Lydia Sellon, he left his two surviving children and immigrated to the United States in 1796 to make his fortune. Charming and quickly connected to all the right people, and armed with stellar design and engineering skills, Latrobe was able to quickly launch a career in a country longing to establish its own grand architecture.

Latrobe knew everyone who was everyone. Here's a profile sketch he "stole" of President George Washington in 1796 while dining at Mount Vernon.

| |

| Latrobe's sketch of President Washington, 1796. Courtesy of the Frick Art Reference Library. Original in Mt. Vernon Ladies Association collection. |

Latrobe is credited with introducing Gothic Revival style to American domestic architecture, and with creating

private and public masterpieces. He also became friendly with Thomas Jefferson and is considered to be a major influence on Jefferson's design for the University of Virginia. The two men shared architectural interests and ideas, but tension existed over the predominance of Greek revival symbolism which Latrobe popularized in his designs. The White House Historical Association notes that Jefferson often contributed his own design ideas, which stressed their working relationship. Latrobe wrote on one such occasion “I am sorry that I am cramped in this design by his prejudices in favor of the old French books, out of which he fishes everything..." That's not at all surprising, given Jefferson's Francophilia.

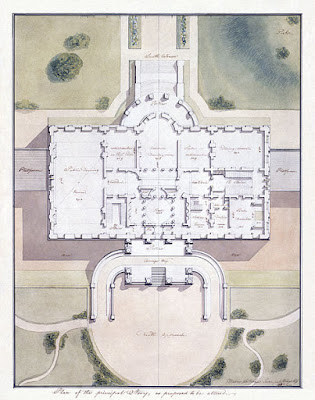

|

| Latrobe's White House plans, circa 1807. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. |

Despite their differences of architectural opinion, in 1803 Jefferson appointed Latrobe to the position of "Surveyor of Public Buildings" and charged him with constructing the south wing of the Capitol Building in Washington DC. This was a much needed appointment for Latrobe, who was constantly plagued with money troubles. He also had a reputation of being a high-strung perfectionist who could be difficult to work with.

The life of an architect and engineer during this period in history was

an itinerant one: you went where the work was. Latrobe worked steadily, receiving commissions for public and private

buildings and infrastructure in Baltimore, Washington DC, and

Philadelphia. But he needed a new gig in 1813 following the

Congressional termination of his position as Surveyor of Public

Buildings in DC. The War of 1812 had interrupted building projects in

the cash-strapped nation, and Pittsburgh seemed to be the place to go

for various reasons.

In coming to Pittsburgh, Latrobe was following a path laid out a few

years earlier by his eldest daughter Lydia and his son-in-law Nicholas

Roosevelt (of the Oyster Bay branch of that family). That couple had

married some years earlier, a union that was against Latrobe's wishes given that Nicholas

Roosevelt was his own contemporary in age and a close friend. Roosevelt had become enamored of Latrobe's daughter Lydia

when she was only 12 years of age. Latrobe found the romance

between his friend and the young daughter of his first marriage

at best laughable and ultimately preposterous. He incredulously wrote to Roosevelt "Were you

really serious?" when he broached the subject of marriage.

Serious they were. Despite various restrictions and multiple delays, the unlikely couple married in 1809 when Lydia was 17 and Roosevelt 41 years of age. Benjamin Latrobe was well-established enough in Washington society that Dolley Madison attended their wedding.

|

| Lydia Latrobe Roosevelt, from Mr. Roosevelt's Steamboat by Mary Dohan |

Latrobe had finally given his blessing to this match and passed along a formal letter of introduction to the newly-wed Nicholas Roosevelt, who came to Pittsburgh in 1809. Roosevelt had been hired to make a flatboat survey voyage down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on behalf of Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston. The trip was meant to determine the feasibility of navigating those waters and hopefully position Pittsburgh as a center of large-scale steamboat construction. Roosevelt agreed to go for a $600 fee -- and so did Lydia Latrobe Roosevelt!

Traveling some 2500 miles during Lydia's second and third trimesters of pregnancy, the couple sailed the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and back in six months. Lydia is said to have designed and furnished comfortable living quarters aboard the flatboat. Their adventures were the stuff of legend and included encounters with

potentially hostile Natives and definitely hostile alligators. Lydia gave birth to their first child, a daughter named Roseta, in January 1810 after the couple returned to New York from their trip.

Nearly two years later, the Latrobe-Roosevelt family set off again, this time on a side-wheeler steamboat. Nicholas, an 8-months pregnant Lydia, toddler Roseta and their Newfoundland dog Tiger left Pittsburgh on the first steamboat voyage ever. Their ship, New Orleans, had been constructed at a yard at the bottom of Boyd's Hill along the banks of the Monongahela River (below where Duquesne University would later be built). This journey took 12 weeks. The Great Comet of 1811 kept them company along the way -- as did little Henry Latrobe Roosevelt, born shortly after they set out October 30, 1811. It's fair to say that the era of steamboat travel was also born on this voyage that originated from Pittsburgh. From 1811 to 1888, boatyards along the Monongahela River produced more than 3,000 steamboats.

Despite the success of the New Orleans, the relationship between the Latrobe-Roosevelts and Robert Fulton was a fractious one. Benjamin Latrobe stood up for his son-in-law in the ensuing business battles. While perhaps wary of Fulton, he remained excited about the future of steam travel and on 13 October 1813, the financially pressured Latrobe moved to Pittsburgh.

Latrobe had hopes of prospering in a steamship partnership with Robert Fulton. The relationship made sense, for Latrobe was an early proponent of steam power, having constructed various steam-powered waterworks in US cities to pipe water into homes. However, a lack of capital, managerial conflicts, competition from established steamboat builders, and a sluggish national economy doomed this Pittsburgh steamboat partnership.

As an agent for Fulton's Mississippi Navigation company, Latrobe engaged in very public disputes over steamboat technology patent rights, writing letters like this one that were published in Pittsburgh's newspapers:

|

| Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 22 July 1814 |

But for all that, Latrobe didn't much appreciate Pittsburgh. He wrote to a friend that "Mud and smoke are the great evils of this town. Whoever can make up his mind to breathe dirt, and eat dirt, and be up to his knees in dirt, may live happily and comfortably here."

Happy and comfortable Latrobe was not, but at least he kept busy. During the year he reluctantly lived in Pittsburgh he designed and built a theater for the Circus of Pepin and Breschard, and at least three private homes presumably incorporating his favored Greek Revival style (none are known to survive). He also expanded an existing church, built steam engines, and even designed a barge. Latrobe was also commissioned to design the United States Arsenal (later known as the Allegheny Arsenal) building in the Lawrenceville section of Pittsburgh. What was eventually constructed differed significantly from his original plans, which are housed at the Library of Congress. Today nothing remains of any of Latrobe's Pittsburgh structures.

|

| "Sketch of the facade of the proposed Arsenal at Pittsburg. 1814. BHLatrobe." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division |

Latrobe and family moved back to DC to oversee reconstruction of the Capitol following the fires set by British troops in 1814. Meanwhile, his son by his first marriage, Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe, had become a civil engineer known for his railway bridges. In 1811, the senior Latrobe had accepted a franchise to design waterworks systems for the city of New Orleans. His son Henry had then secured the commission for the project, and moved there to began construction. Unfortunately a little war with the British intervened, so Henry fought during the War of 1812. He also found time to design a lighthouse and work on New Orleans' Charity Hospital and the French Opera House. Henry contracted yellow fever in 1817 and died in New Orleans at age 25.

A little more than a year after his son's death, and fresh from bankruptcy proceedings, Benjamin Latrobe left DC for a fresh start and to complete the job his eldest son had started. Benjamin traveled to New Orleans to complete his son's work on the water supply system, and his family joined him the following year. In New Orleans, Latrobe designed the Louisiana State Bank and the central tower with clock and bell of the Saint Louis Cathedral. This tower collapsed in 1850 during reconstruction, but the bell was reused in the new building and remains there today.

But like his son, and so many other visitors to the city, Benjamin Latrobe contracted yellow fever. He died in New Orleans on 2 September 1820. Both father and son were buried in a communal lye pit, a typical method of interment during Yellow Jack outbreaks. The Latrobes are remembered with a memorial marker in Saint Louis Cemetery #1 that was erected by their descendants.

|

| Latrobe Memorial, St Louis Cemetery #1, New Orleans LA |

Latrobe and his second wife Mary Elizabeth Hazlehurst had one surviving daughter, Julia E. Latrobe, who never married. Although she lived to the age of 86, Julia seems not have left anything as a legacy beyond a circa-1812 manuscript in which she recorded dance steps and reminiscences of her childhood, and various party invitations and greeting cards. These items are in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society.

There were two surviving Latrobe sons.

John Hazelhurst Boneval Latrobe was a Maryland attorney who was retained as counsel for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. He

had aspired to a career in architecture, but abandoned this idea due to

family financial circumstances following his father's death. He was,

however, a talented landscape artist and art patron, and illustrated and

wrote a drawing manual under the pseudonym E. Von Blom. He was also

known to be a prominent supporter of the African colonization of

Liberia, a well-intentioned but misguided antebellum movement. John H.

B. Latrobe kept a journal called "Southern Travels" written during a

two-month period in late 1834. In it, he chronicled his travels with his

wife Charlotte from New York to Natchez (where wife had family), and

the return trip by stagecoach to their Baltimore home.

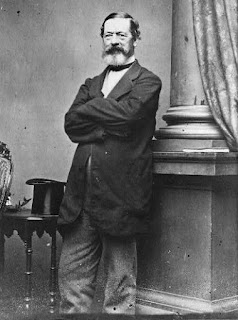

|

| John H. B. Latrobe, c.1860-90, photo from Brady negative. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. |

Youngest son Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Jr initially studied law under big brother John, working on cases involving his late father's property disputes. He then assisted his brother in drafting provisions for the original Maryland charter of the B&O RR, which involved surveying and field work. This awakened latent mathematical abilities that he decided to pursue. Junior, as he was sometimes known, eventually became chief engineer of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, laying out the line between Washington DC and Baltimore and designing the Thomas Viaduct outside the latter city. He had a distinguished career as a civil engineer, and was the guiding force in extending the B&O into Pittsburgh by absorbing a Connellsville railroad company.

|

| Benjamin Henry Latrobe II |

While the Pittsburgh buildings constructed by Benjamin H. B. Latrobe are gone, Western Pennsylvania residents have an abiding connection to the Latrobe family: the town of Latrobe.

|

| Latrobe, Pennsylvania birds-eye view map circa 1900. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division. |

Ironically, the town has but a tangential connection to the family. According to the Latrobe Historical Society, Oliver Barnes purchased a 140 acre farm in Derry Township in 1851 for the Pennsylvania Railroad, which wanted to connect the eastern part of the state with Pittsburgh and planned to build railroad yards. Pplans changed and the yards were built instead in Derry, so Mr. Barnes acquired the land for himself. He laid out streets and lots and named his new town Latrobe in honor of his friend and railroad associate, Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Jr. None of the Latrobe men are known to have set foot in the town bearing their surname.

New Orleans, Latrobe's eternal home, remembers him in other ways.

Near the French Market arch at Ursulines Street is a small park

dedicated to Benjamin Latrobe. The site of this park is actually the

former waterworks that father and son designed and created. The park

incorporates architectural remnants from the works into its sculptures

and fountains.

__________________________________

Further reading:

Baker, Jean H. Building America: The Life of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Oxford University Press. January 2020.

Eaton, Leonard. Houses and Money: The Domestic Clients of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. William L Bauhan. January 1988.

Hamlin, Talbot. Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Oxford University Press; 1st edition. 1955.

Latrobe, Benjamin Henry. The Journals of Benjamin Henry Latrobe 1799-1820. Yale University Press. 1980.

Latrobe, John H. B. Southern Travels: Journal of John H. B. Latrobe. Historic New Orleans Collection; First Edition. 1986.

The Versatile Benjamin Latrobe

Sutcliffe, Andrea J. Steam: The Untold Story of America's First Great Invention. Palgrave Macmillan. 2004.

A chapter of my book "The Aubry's - Free People of Color in Early New Orleans" has a chapter devoted to Henry Sellon Boneval Latrobe and his days in New Orleans, along with the story of the free colored family he founded there.

ReplyDelete